This post was written by David C. Weinczok.

For many people not fortunate enough to grow up with a castle in their proverbial backyard (like me), books, video games, films and television shows are the first places they will encounter castles. Such images often stay with people for life and inform their view of what the medieval world would have looked like. I see this as an asset for historians and heritage professionals rather than a hindrance – sure, pop culture doesn’t have a great track record with getting the historical details right, but if it sparks an interest in castles where one might never have arisen that, to me, can only be a good thing.

I’m using the world of fantasy and fictional castles as way to discuss the real deal in a talk for Previously…Scotland’s History Festival on Nov.19th in Edinburgh. My aim is to put the defences of famous fictional castles to the test – would, for instance, Mickey be able to withstand a siege if he holed up in the Disney castle? Do the fortresses of Game of Thrones actually make sense or are they all show? How hard would it be to rescue a princess from the Super Mario castles?

To find out, I’m applying several criteria to each that can just as easily be used to assess the battle-readiness of real castles. For instance, are their turrets, crenels and wall-walks actually capable of bolstering their defence, or are they in fact just for aesthetic flair? Is their architecture specifically tailored to the demands of their environments? Are there multiple layers of defence, or do all hopes rest on a single strongpoint?

Let’s take Game of Thrones’ Winterfell as an example. I hate to challenge the might of a castle that has famously been untaken for ‘thousands of years’, but for that to be the case they can’t have had a single decent winter in millennia. Take a look at many of the tower roofs in the image below. Notice anything peculiar about their design?

That’s right – a castle specifically designed to resists winter employs flat roofs on many of its towers. Why is this a problem? Because those roofs need to bear weight, and accumulated snow is immensely heavy. So, unless the towers are upheld by some ancient magic, their roofs will come crashing down with the first heavy snowfall. Perhaps the name ‘Winterfell’ is actually an architect’s very reasonable warning about the weather!

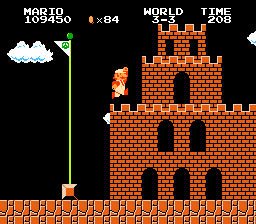

The first castles I probably saw outside of Alan Lee’s illustrated version of The Lord of the Rings were the castles in the original Super Mario. Now, I know they weren’t designed to be overly scrutinised by nitpickers like me and the graphical limitations of early 1990s video games meant simplicity was key. But let’s take a look.

Credit where credit is due for having functional wall walks with crenellations and merlons that are actually high enough to fully shelter an archer. But we really need to talk about those windows. As a general rule of thumb, more windows means less defensive capability, and the larger the window the further that defence is compromised. The windows on Super Mario’s castles are clearly exaggerated, but it’s not hard to find real-life parallels. Take one of Scotland’s most famous castles, Kilchurn on the banks of Loch Awe.

Often thought of by visitors as an impregnable fortress, its western face leaves much to be desired. Kilchurn was never, in fact, a true fighting fortress but more of a domestic seat with castellated features. No stronghold hoping to stand against a determined foe would dare give them so many openings through which to fire and breach.

These are just a few examples of what I’ll be discussing, and there will be some surprising winners as well as losers out of it. It is my hope that talks like this will get people who have already been exposed to castles through pop culture to think more critically about them, all while having a bit of fun.

David is a writer, presenter, and castle hunter, and you can find more from him on Twitter, Instagram, and his website.