Giles Carey project lead for the Castle Pulverbatch survey, funded by the Castle Studies Trust, presents an overview of the wider settlement context for the motte and bailey at Castle Pulverbatch, central Shropshire.

“It is a truism that medieval castles ‘dominated’ their landscapes. But this apparently simple statement obscures, and indeed misrepresents the many and varied ways in which castles were both embedded in the medieval landscape and contributed to its evolution and character.” (Creighton and Higham, 2004: 5).

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

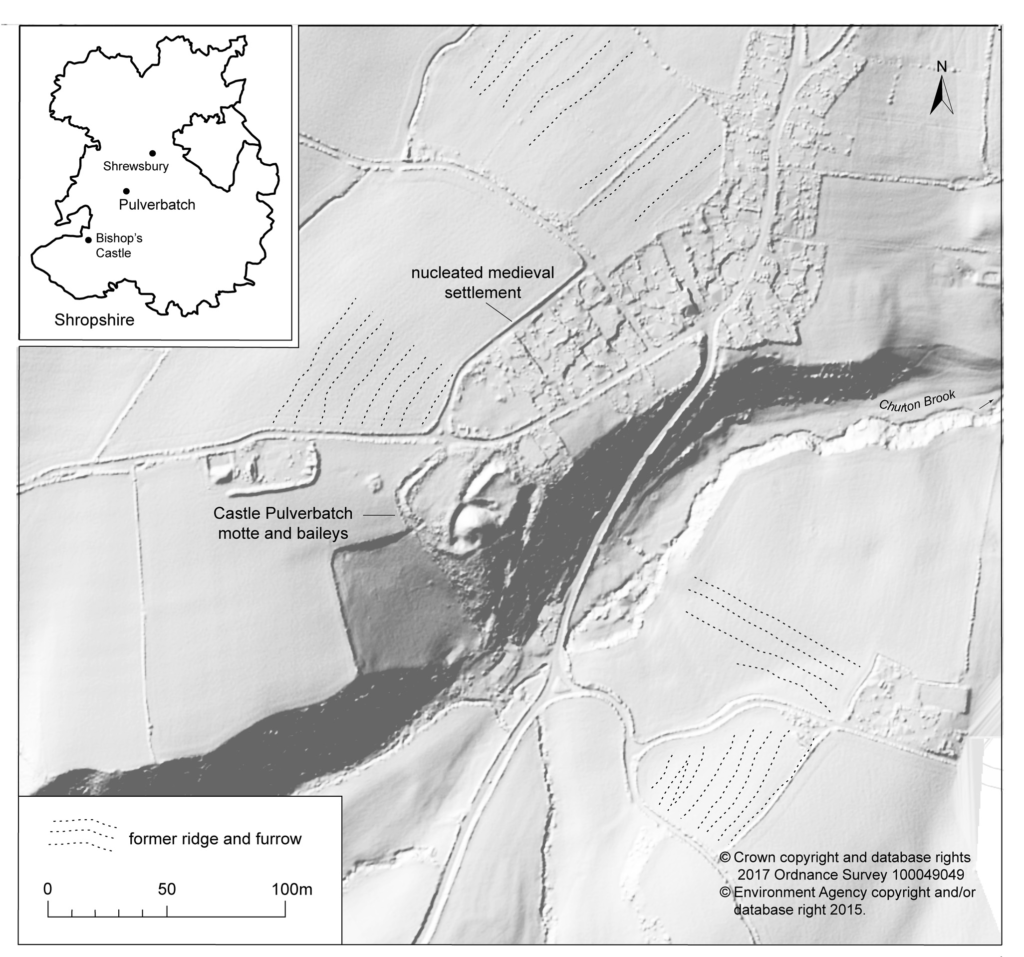

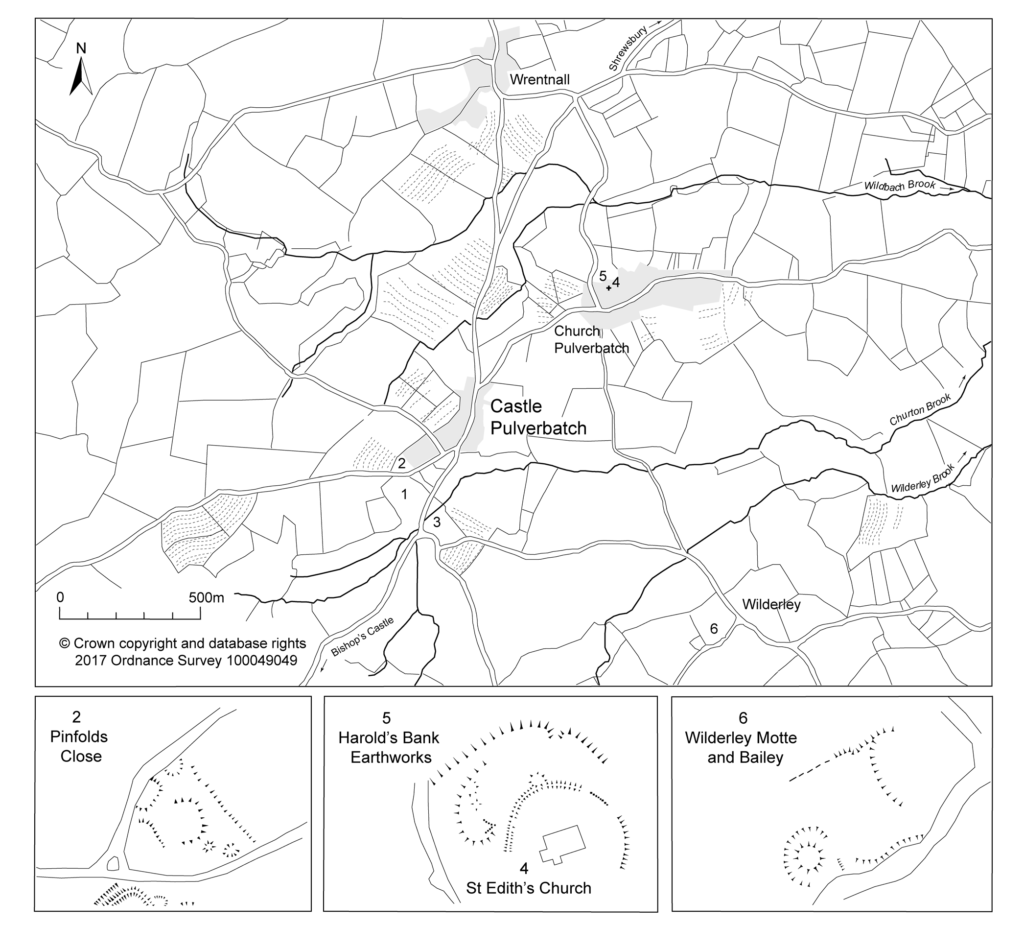

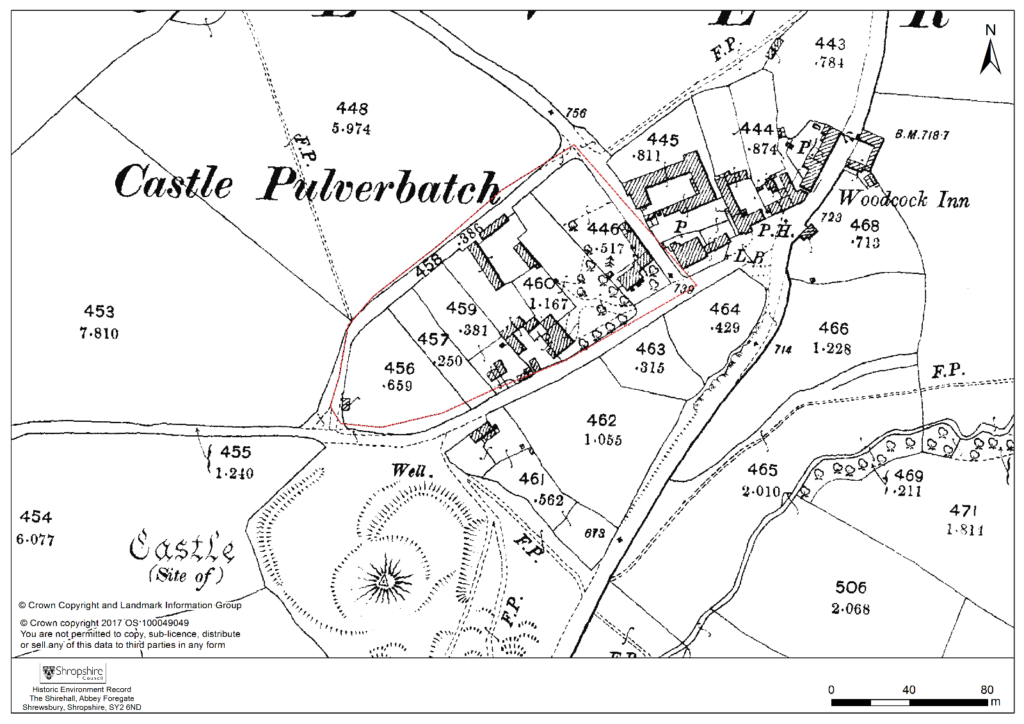

Pulverbatch is a village situated in central Shropshire, about 13km southwest of Shrewsbury on a minor road from Shrewsbury to Wentnor. The modern village is formed of two distinct centres, with a small nucleated settlement around the church (Church Pulverbatch, known as ‘Churcheton’, then Churton since at least the 13th century (Gaydon, 1968: 138)), and Castle Pulverbatch lying c.1km to the SW. One of Shropshire’s best-preserved motte and bailey castles is situated on the edge of a small steep-sided ridge at the southern end of the village (figure 1).

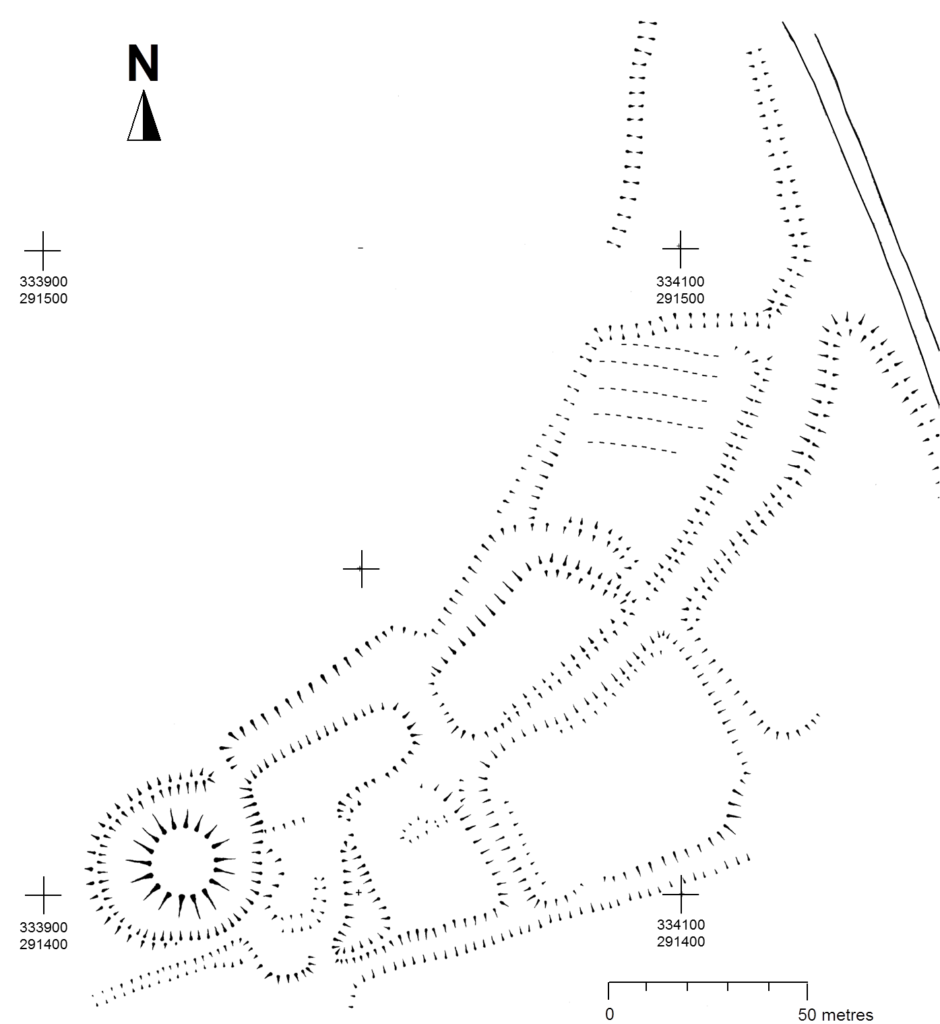

The castle comprises a roughly circular motte, with a base diameter of 35m standing up to 8m high, constructed on the edge of a ridge to make the best use of the natural topography. A substantial ditch 7m wide and 2.6m wide, with a counterscarp bank 4m wide and 0.8m high, separates the castle motte from the flat ground to the west. The inner bailey, situated to the north-east of the motte, is roughly rectangular in plan. It measures 28m north-east to south-west by 30m south-east to north-west. Around its north-west and north-east sides, the bailey is defended by a substantial bank up to 10m wide and 4.2m high on its outside, 1.5m high on its inside. The south-east side of the inner bailey is not defined by a bank but makes strategic use of the natural topography to provide a defendable location. The outer bailey, standing to the west, is, by contrast, defined by much slighter defences. This difference in construction has been suggested as indicating a two-phase construction for the site, with the outer bailey representing the enlargement of a compact and strongly defended initial structure (Stillman, 1980: 3). The outer bailey extends 80m north-south by 40m east-west. A defensive bank up to 6.5m wide and 1.4m high runs along its north-west side, defining a deep hollow-way which runs adjacent to the field boundary in this location.

Strategically, the castle occupies a dominant location on the edge of a spur extending south from the village of Castle Pulverbatch. From the top of the motte, views run along the valley of the Churton Brook, and cover the road network (figure 2). It has been suggested that the castle could have provided a control point over “the route from hill country to the Severn valley, perhaps levying a toll on traffic” (Stillman, 1980: 18).

Castle Pulverbatch is typical of rural earthwork castles in Shropshire and the wider Marches. It appears to form an outlier for a concentration of 12 similar motte and baileys in the Vale of Montgomery, from Montgomery in the south-west to Caus in the north-east (Cathcart King and Spurgeon, 1965). These small, rural castles have a number of key characteristics – mottes with a very restricted top, which would have been capable of carrying only a small structure – a ‘blockhouse or pill-box’ as Cathcart King and Spurgeon refer to them, overlooking strategic points on the road network. Pulverbatch certainly meets this criterion – it’s motte ‘dominates’ routeways at the northern approaches to the Long Mynd and the western flank of the entrance to the Stretton Valley.

In 2017-2018, The Castle Studies Trust, and the Shropshire Archaeological and Historical Society provided grant-funding for geophysical surveys on the site, together with a level 2 earthwork survey using photogrammetry (Donaldson and Sabin, 2017; Stanford, 2017; Ashby, 2018). The results of this work were informative, and suggestive of a substantial building, measuring 22m by 18m in the inner bailey. Background research, however, drew attention to the wider landscape. It soon became clear that the story of the castle would only be ever half-complete if one focused on the earthworks and buildings of the inner and the outer bailey. The inter-relationship between the motte and bailey, its associated settlement and the parish church of St. Edith was evidently worthy of further exploration (figure 2).

Castle, settlement and church

Pulverbatch is first mentioned in the Domesday Survey of 1086 when it appears as ‘Polrebec’. The name derives from Old English, a combination of pulfre of unknown meaning and bǣce meaning stream valley (Gelling 1990, 245–7). At Domesday, the manor of Pulverbatch, combining both modern settlements of Church and Castle Pulverbatch, was held by Roger Venator [The Hunter]. Roger Venator was a tenant of Roger de Montgomery, Earl of Shrewsbury. Along with his brother Norman, he was a huntsman for the Earl and was consequently granted land in the Shropshire forests. He also held nearby Wrentnall.

Domesday records Pulverbatch as comprising two hides of land which paid tax, and there was land for five ploughs: two ploughs in the lordship with four slaves, while seven villagers had a further three ploughs between them. There were also two ‘radmans’ [riding men – the lord’s servants] in the manor. There was enough woodland for the fattening of 100 pigs. Before 1066, the manor had been worth £6 in tax; that had dropped to 20s in 1066, but by 1086its value had risen to 30s (Eyton 1854, 189).

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

The evidence suggests that the castle was built towards the end of the 11th century, either by Roger Venator or his son, also called Roger. Castle Pulverbatch is one of eighteen or more earthwork castles in south-west Shropshire that were built by the first Norman lords installed by Roger de Montgomery, himself one of three key lieutenants installed by William the Conqueror following rebellions in the Welsh Marches in the later 1060s. Documentary sources refer to the castle still being occupied in 1205, but there is no trace of a manor-house here in documents of 1292 (Gaydon 1968, 131).

Another motte and bailey lies 1.2km to the south-east, north of Wilderley Hall Farm (Figure 3, site 6), which at Domesday was held by another minor tenant of Roger of Montgomery, Hugh Fitz Turgis (Eyton 1854, 258). Probably, like Castle Pulverbatch, Wilderley was positioned strategically to command a route running northwards from the Long Mynd towards the Severn Valley (Gaydon 1968, 132). Little is known about the history of Wilderley so establishing any chronological link between the two castle sites remains challenging.

In 1254 Philip Marmion was granted the right to hold a weekly market at Pulverbatch on Mondays, and an annual three-day fair around the day [16th September]of St Edith the Virgin’, to whom the church in Church Pulverbatch was dedicated (Eyton 1858, 197).

At an inquest on the death of Philip Marmionon January 14 1292, his estate at Pulverbatch included a ‘capital messuage [house, yard, outbuildings and land], a carucate of arable land, and two acres of meadow. A Mill realised 30s…’ (Eyton 1858, 199). The latter was presumably on the site indicated by slight earthworks in a field identified on the tithe map as Upper Mill Meadow (Figure 3, site 3).

There is no clear dating evidence concerning settlement at Pulverbatch. The chronological picture is further complicated by the suggested early date for a church at Church Pulverbatch (Figure 3, site 4). The present building is medieval in origin, although it was largely rebuilt in 1853 (Newman and Pevsner 2006, 203–4). (A lovely watercolour of the pre-19th century form of the church is held by Shropshire Archives, and a small version can be accessed via their online catalogue: https://www.shropshirearchives.org.uk/collections/getrecord/CCA_X6001_19_372B_4)

The church lies within a circular, embanked churchyard, which has been suggested as indicating an early, possibly pre-conquest origin, drawing upon other examples from the Marches (Rowley 1972, 81), although this hypothesis is untested in the county (see Ludlow 2009, 71-76 for discussion of examples from south-west Wales). A number of other circular churchyards are known in Shropshire (Cardeston, Stanton upon Hine Heath, Llanymynech, Loppington and Leighton, inter alia), but the importance of that at Pulverbatch is heightened by the presence of additional earthworks to the north of the churchyard, occupying a high point within the wider landscape (Figure 2, site 5).

A number of authors have speculated about the development of the medieval settlement sited immediately north and west of the castle (figure 4). Little earthwork evidence survives of this settlement, although a slight bank was recorded in the 1980s by Stillman on a triangle of land known as Pinfold’s Close, directly to the north of the castle’s outer bailey. This triangle was suggested as a possible plot division (see Figure 2, site 2) and subsequently recorded as a property/field boundary by Wendy Horton on a site visit in 1991 (Shropshire HER PRN 03703). Sadly, this area has been extensively disturbed since then, and little trace of any earthworks was found during the 2017-2018 survey work.

Higham and Barker see the village ‘growing up around a castle founded in previously open countryside’ (Higham and Barker 1992, 200) while Rowley suggests that its regularity indicates a deliberately planned settlement unit laid out by the lord of the manor in the 12th or 13th century (Rowley 1972, 86). Creighton goes further in identifying the development at Castle Pulverbatch as representing a nucleation point, “a regular settlement” growing up adjacent to the “new seigneurial centre” (Creighton 2002, 203). This would accord well with the manor of Pulverbatch becoming the caput baroniae, or principal manor of the baronry of Pulverbatch by the end of the 12th century (Gaydon 1968, 131). Stillman suggests that the settlement around the castle may have been a fairly speculative endeavour from the lord of the manor that was ultimately unsuccessful, with settlement shifting downhill to the modern settlement at Church Pulverbatch (Stillman 1980, 18). There is no evidence of the settlement at Castle Pulverbatch ever expanding into ‘anything more than a small farming community’ (Gaydon 1968, 132).

This relationship between the development of a settlement, and the development of a castle site has been little explored in the region. Whilst the extensive work at the motte-and-bailey site of Hen Domen in the 1970s revolutionised our understanding of the likely former structural complexity of timber castles in general (Higham and Barker, 1972), there has been little opportunity to further investigate the significant group of motte and bailey castles in the Vale of Montgomery and SW Shropshire, including inter-relations between settlements and castle.

Some of these complexities can be seen at the site of Caus Castle, was subject to a detailed programme of earthwork and geophysical survey in 2016, also funded by the Castle Studies Trust (Fradley and Carey, 2016). Although a castle of quite different status, size and setting to that at Pulverbatch, work here provided evidence of a castle, borough, market (and later fair) in states of flux, and indicated that the fortunes of the castle and the fortunes of the town were not always aligned.

A number of other small, earthwork castles in this part of the march would repay such further study. We might think the castle at More, for instance. A motte and bailey castle developed here from an earlier ringwork castle, with its associated earthwork remains of a deserted settlement, with the remains of house plots and toft boundaries (figure 5).

Non-intrusive landscape survey, as funded by the Castle Studies Trust, allows us to place these sites in some context, and allows a glimpse at the bigger seigneurial, tenurial and topographic picture of these earthwork castles.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Featured image Castle Pulverbatch bailey from motte top.

Bilbliography

Ashby, D., 2018. ‘Castle Pulverbatch, Shropshire: Ground Penetrating Radar Report’, unpublished report, ARCA, University of Winchester.

Carey, G., 2018. Capturing the Castle: recent survey work at Castle Pulverbatch Motte and Bailey, Shropshire, Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological and Historical Society 93 pp.31-44

Cathcart King, D. and Spurgeon, C., 1965. ‘The Mottes in the Vale of Montgomery’, Archaeologia Cambrensis 114 pp.69–86.

Creighton, O. and Higham, R., 2006. ‘Castle studies and the ‘landscape’ agenda’, Landscape History 26 pp.5–18

Creighton, O. H., 2002. Castles and Landscapes. London: Continuum

Donaldson, K., and Sabin, D., 2017. ‘Castle Pulverbatch Motte and Bailey, Shropshire: earth resistance & magnetometer survey report’, unpublished report, Archaeological Surveys Ltd., report no. J708. Shropshire HER ESA 8253.

Eyton, R., 1854. Antiquities of Shropshire Volume 6. London. John Russell Smith.

Fradley, M. and Carey, G., 2016. ‘Archaeo-topographical survey: Caus Castle, Westbury — a preliminary report’, unpublished report. Shropshire HER ESA 8179.

Gaydon, A. (ed.), 1968. The Victoria History of Shropshire: Volume VIII. London. Oxford University Press.

Gelling, M., 1990. The Place Names of Shropshire. EPNS, Vols. LXII/LXIII (Part One).

Hannaford, H., and Silvester, R., 2015. ‘Desk-based studies of four castles in the Welsh Marches: Castle Pulverbatch, More Castle, Wilmington Castle & Hyssington Castle’, unpublished report, SCAS, report no. 371. Shropshire HER ESA 7514.

Highham, R. and Barker, P., 1992. Timber Castles. Exeter: University of Exeter Press

Ludlow, N., 2009. Identifying Early Medieval Ecclesiastical Sites in South-West Wales In: Edwards, N. (ed.) The Archaeology of the Early Medieval Celtic Churches London: Routledge, pp.61–84.

Pevsner, N. and Newman, J. 2006. Buildings of England: Shropshire. London: Yale.

Rowley, T. 1972. The Shropshire Landscape. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Stanford, A., 2017. ‘Castle Pulverbatch Processing Report’, unpublished report, Aerial Cam, report no. C-P-01042017.

Shropshire HER ESA 8254.

Stillman, N., 1980. ‘Castle Pulverbatch: a field survey of a motte and bailey earthwork in Shropshire’, unpublished report, University of Birmingham. Shropshire HER ESA 1137.

Thorn, F., and Thorn, C. (eds), 1986. Domesday Book: Shropshire. Chichester