Alison Norton, PhD student at Christ Church Canterbury, who is studying medieval castles and landscapes in South West England looks at one of the castles she is studying as part of her research, Coldridge in Devon.

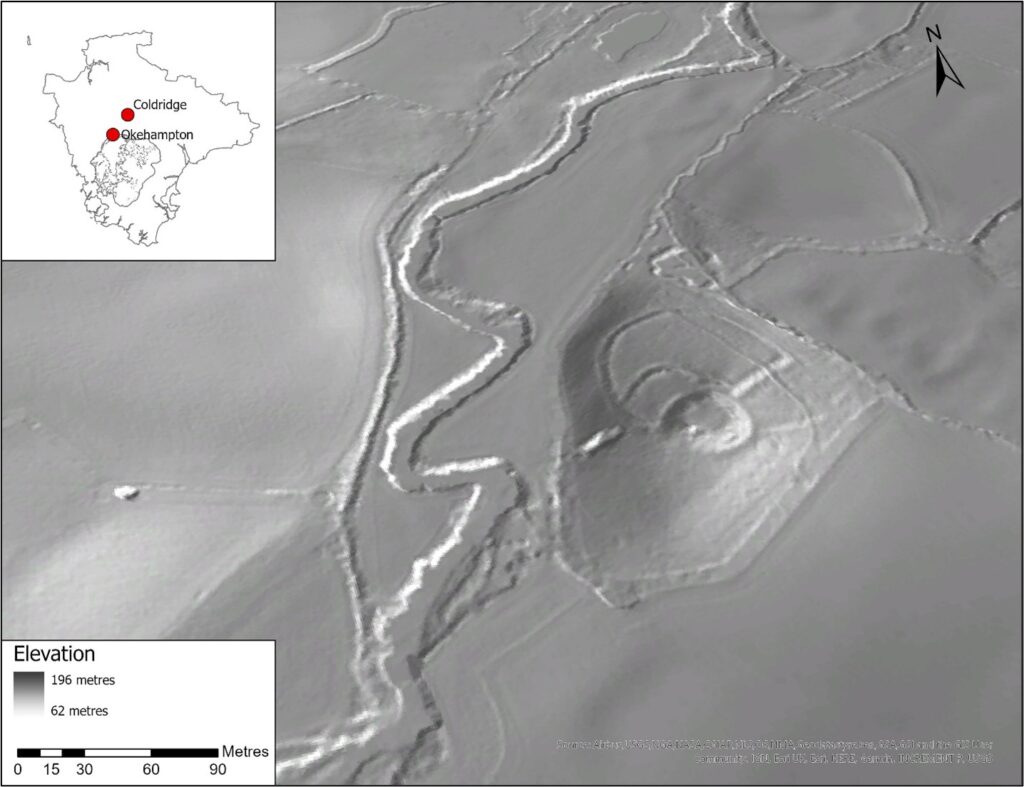

Coldridge Castle is a motte and bailey located in Mid-Devon, roughly 16km northeast of Okehampton (Figure 1). The castle sits within dense woodland, known locally as Castle Wood, along the eastern banks of the River Taw. Past investigations of Coldridge and its community are limited to gazetteer entries due to a scarcity of text-based and archaeological source material. This evidence gap has resulted in a lack of historical and archaeological context of Coldridge as an individual site within its surrounding landscape. To provide context and understand why castle builders chose this particular site, my research first utilised place name and landscape evidence. This source material provided a framework for me to computationally generate theoretical landscape models and test siting theories using GIS and LiDAR.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

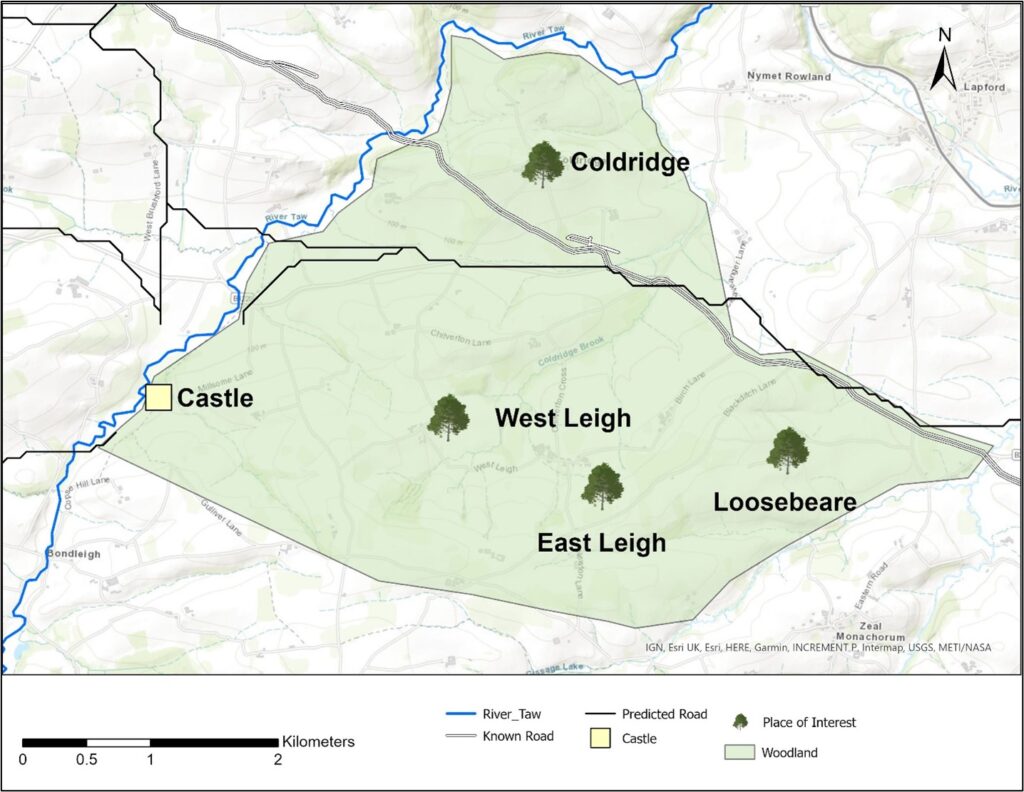

Coldridge (Old English for “charcoal ridge”) indicates a pre-Conquest landscape of the production and trade of charcoal. This resource was a valuable fuel source and was likely supplied to surrounding estates, such as Crediton and Winkleigh. As a charcoal-burning site, the community would have been integral to the local economy, requiring easy access to various trade networks. In addition, given charcoal-burners heavily relied on a continuous supply of coppice, Coldridge would need to be positioned in a well-wooded landscape. When expanding my landscape analysis to include surrounding estates, place-name, and supporting Exon Domesday, evidence highlights two manors, Leigh and Loosebeare, that indicate the local area was predominantly woodland (Figure 2).

It is very likely, based on this source material, that woodland associated with Leigh (Old English for “wood”) and Loosebeare (Old English for “place that pastures pigs”) was contiguous with that of Coldridge. This wooded characteristic of the castle’s surrounding landscape incorporates ideas of seasonality regarding visibility from and of the site. My initial thoughts about this seasonal element were as follows: I thought travellers moving along local trade routes would have limited visibility of the castle. This observation could also apply to the castle having limited visibility of movement within its surrounding landscape. Second, it felt possible castle builders were primarily influenced by the need to have targeted visibility over local production.

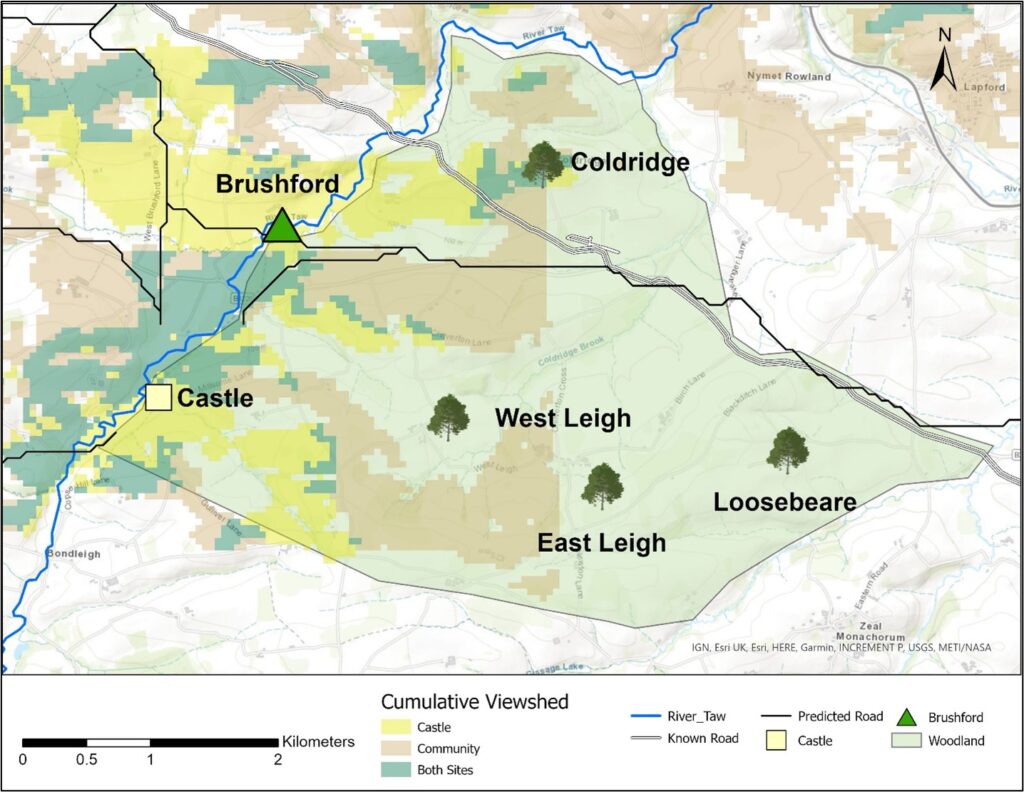

To test these theories, I applied least-cost path and viewshed analyses. The former is a tool that predicts movement between various places of interest. It takes topographic and elevation data and generates predicted routes that exert the least amount of energy or time to travel to and from said points. The latter is a tool that analyses visibility from a specific point within the landscape. Viewsheds show what is visible and not visible to an observer and can be adjusted to include various heights and distances. For example, a viewshed can determine what is visible within a 2km radius to an observer standing atop a 9m tower. Results from these analyses revealed the castle had concentrated views over its immediate surroundings, particularly the bridge in the neighbouring manor, Brushford. In contrast, the castle’s viewshed showed sporadic visibility over predicted routeways that could indicate monitoring movement to and from Coldridge was not a primary factor in castle siting decisions. When I applied viewshed analyses from routeways and surrounding estates, results showed travellers moving east towards the castle from Brushford and Winkleigh held more targeted views of Coldridge. Further research is in progress, though it is probable visibility over the production and trade of charcoal were the primary influencers for castle builders as opposed to sweeping visibility over the landscape (Figure 3).

If any other student would like to promote their work with a short blog post on our site, the Trust would be interested in hearing from you. You can contact us at admin at castlestudiestrust.org .