In the Castle Studies Trust’s first year of grant awards it gave a grant to survey Ballintober Castle in County Roscommon, caput of the O’Conors. Project lead Niall Brady explains below how that work has been built on and what has been discovered since.

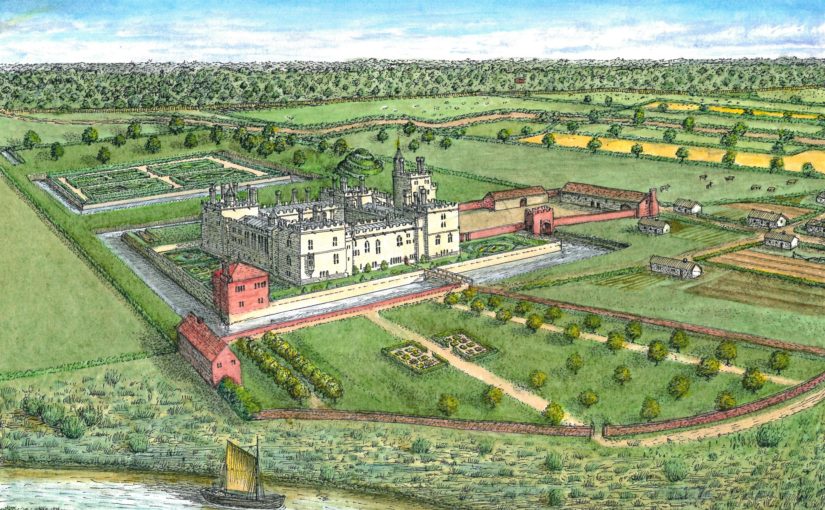

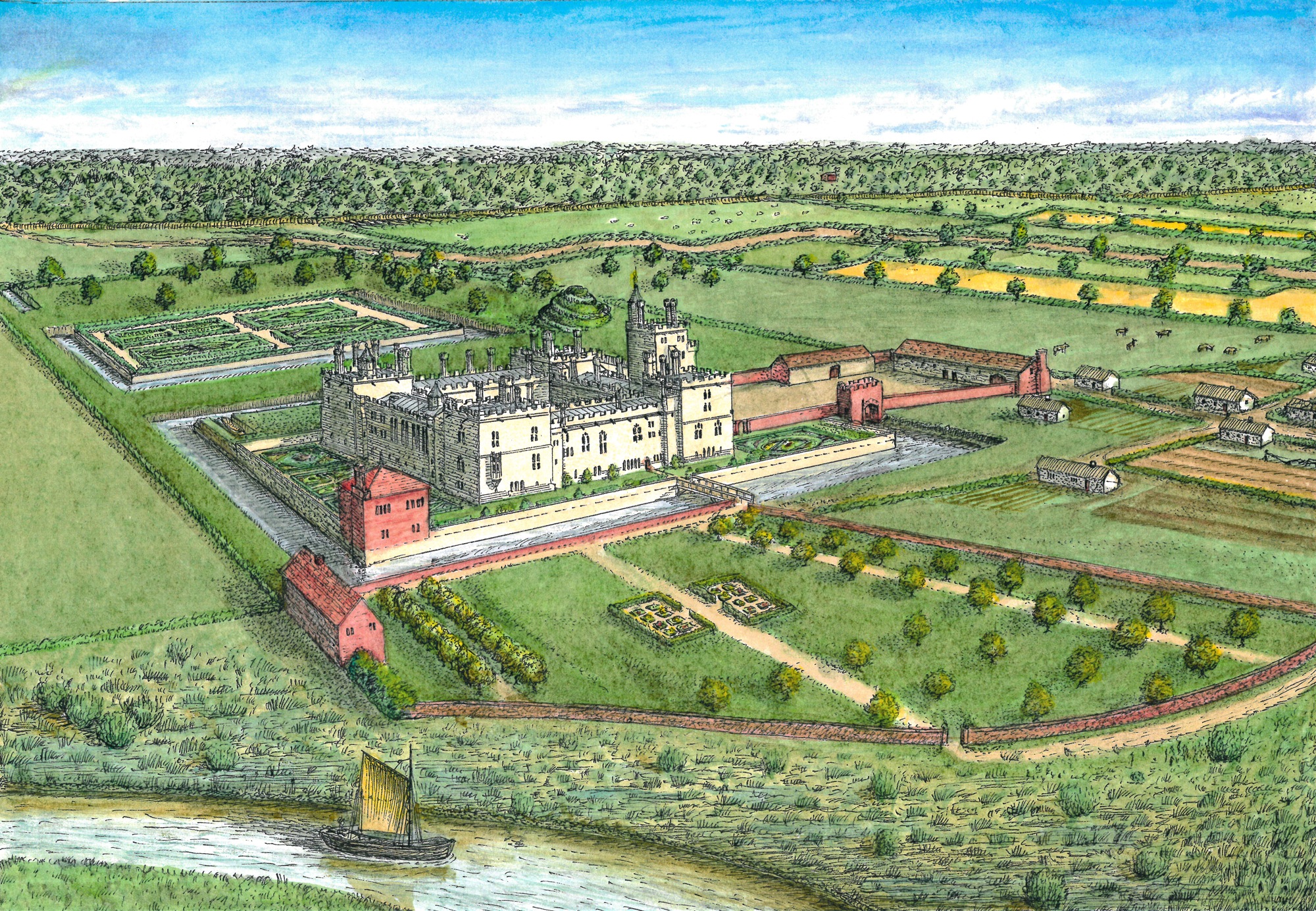

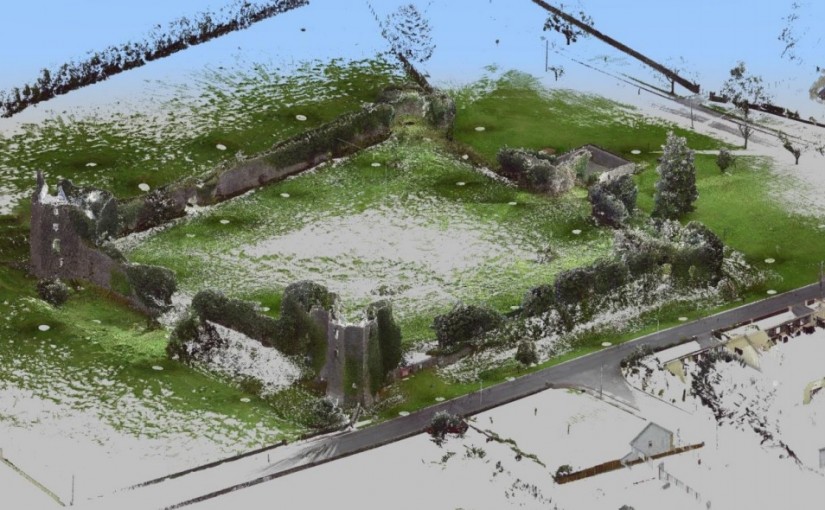

The Castle Studies Trust grant of 2014 for Ballintober Castle permitted a detailed baseline topographical survey of the 14th-century Anglo-Norman castle, constructed in the early 1300s by Richard de Burgh, earl of Ulster, and taken over by the O’Conor kings of the Connacht before the end of the century, after which it became the caput of the O’Conor Don line and was lived in continuously until the O’Conors abandoned the castle for more suitable accommodation at nearby Clonalis House in the 1700s.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

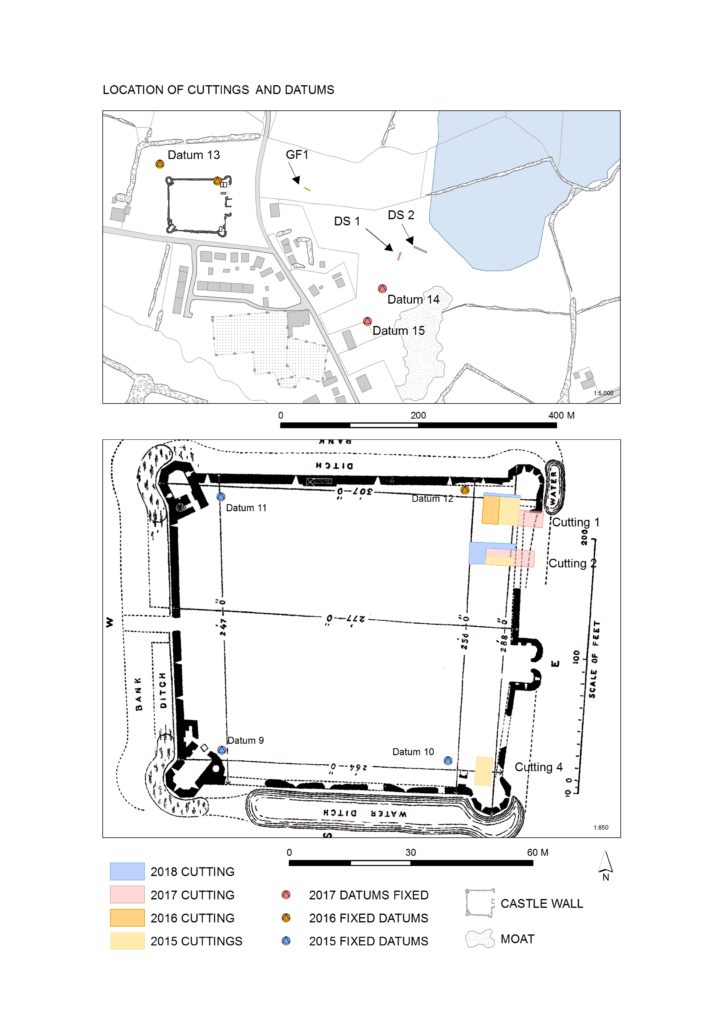

The castle remains a striking ruin in the small village of Ballintober and access to the site is prohibited because of its dilapidation. The 2014 survey feeds into a long-term plan by the O’Conors who retain ownership to rehabilitate the site so that it can be accessible once again and enjoyed. Since 2015, the Castles in Communities research fieldschool has taken a leading role in developing this initiative as a community-engaged anthropological and archaeological Summer fieldschool that sees groups of up to 70 students and staff coming over from America in July, working closely with the O’Conors in Clonalis House and the village represented by the Ballintubber Tidy Towns organization. Additional survey, coupled with geophysical survey, field survey and excavation has made great strides in revealing the complex history of the castle, while a conservation management plan for the castle was completed independently in 2016.

The fieldschool’s work has also extended outside the standing walls of the castle. In reaching eastwards across the present-day village, the project has confirmed the presence of a deserted settlement that would have been integrally related to the castle. In short, Castles in Communities has revealed the deserted manorial village that was associated with the castle and the findings indicate that the medieval settlement footprint was fully twice the size of the present-day village. Excavation within the deserted settlement area is focusing on taking cross-sections across former property plots and the houses within.

Photograph of cutting opened along the castle entrance in 2019, where evidence for two principal phases of construction have been identified. Siobhan Boyd, project director, explaining the findings.

Excavation inside the castle has progressed along the east side of the interior, where perimeter walls are lower and there is no risk of destabilizing standing remains. Attention has focused on the corner towers, and the perimeter wall. The southeast corner tower is circular in plan but its interior was robbed-out at some point in the past, leaving only a narrow and thin occupation deposit that retained post-medieval ceramics. The northeast corner tower is rectangular in shape, and excavation revealed a large building joined to the tower and running south from it. That building is late in the construction sequence and is itself joined to an earlier masonry structure that lies inside the walled perimeter. The indications for an early phase of castle building that might pre-date much of the standing perimeter walls is also indicated at the castle entrance, where excavation has begun to reveal two distinct phases of construction.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

The project will continue in 2021 after Covid-19 restrictions are lifted.

Niall Brady

Project Director (one of 6)

Castles in Communities

https://sites.google.com/view/irelandcastlesincommunities

email: nbrady@adco-ie.com