Dr Jonathan Clark, Historic Buildings Director, FAS Heritage and project lead for the Castle Studies Trust funded 3-D Reconstruction of C12 Lincoln Castle explains how it was done and the challenges faced in doing it.

A virtual 3-D reconstruction of Lincoln Castle as it may have looked in the late 12th-century has been completed by Peter Lorimer, Pighill Illustration in collaboration with FAS Heritage. The reconstruction was funded by the Castle Studies Trust and made possible through 15 years of archaeological research for the Lincoln Castle Revealed project. The project consisted of a £22m repair and restoration programme to conserve the site and renew the visitor experience funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund, Lincolnshire County Council and the European Regional Development Fund. The programme provided opportunities for research-led archaeology which yielded a wealth of new information about the site.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

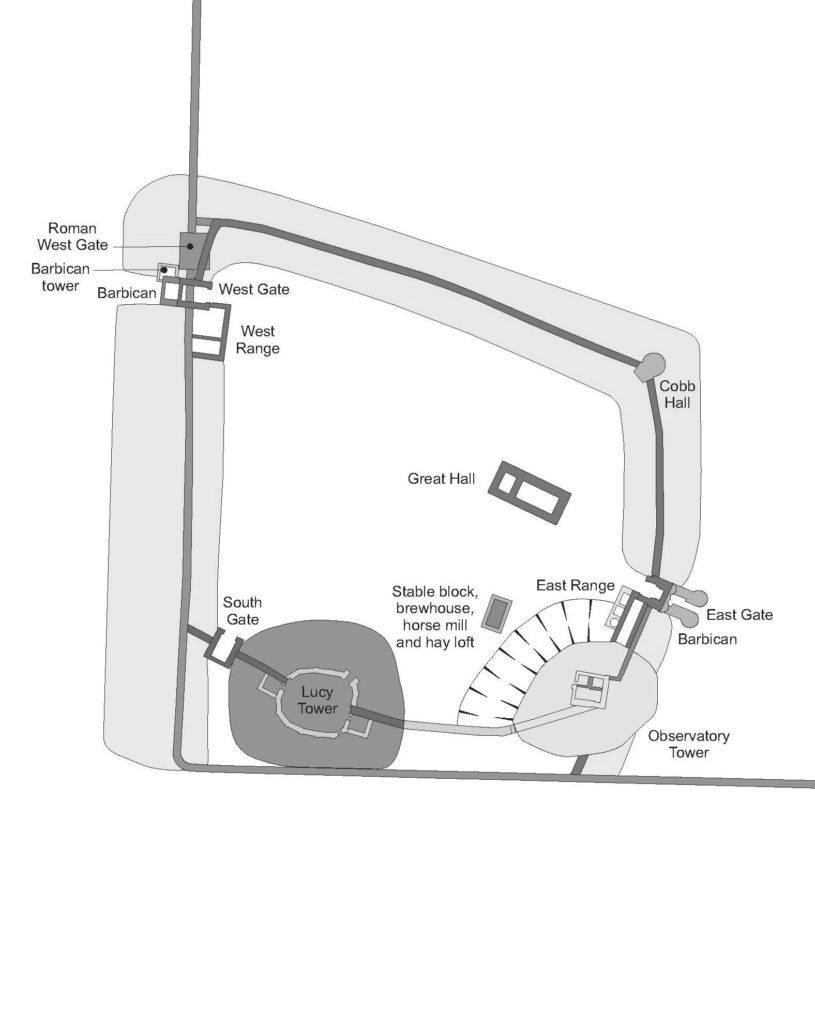

William the Conqueror established Lincoln Castle in 1068 in the walled enclosure of the former Roman colonia. The Lucy Tower motte was built in its southwest corner reusing the west and south walls to defend the new inner bailey. The next 100 years saw rapid development: originally earth and timber, the Conquest-period castle was replaced in masonry, a process now understood to have started by the 1080s including East and West Gates; by the early 12th century the stone enclosure of the bailey and internal gate ranges were complete, along with the Lucy Tower shell-keep and later Observatory Tower. Inner bailey buildings were also contacted during excavation including the Great Hall, stables, East Range and the Observatory Tower motte and ditch, all contributing information to the reconstruction. Evidence for a lost South Gate to match East and West Gates was found; along with a reappraisal of the early form of the Lucy Tower shell-keep it provided information about a former southern enclosure. This enclosure was abandoned, probably by the early 13th century, when the castle contracted to the form of the current enclosure.

It was the culmination of this intense century of development, arrived at by the late 12th century that was selected for the digital reconstruction.

Archaeological excavation and detailed building recording formed most information about the early form of the castle, but the assembly of the 3-D reconstruction led to reappraisal of other parts of the castle; previously unnoticed anomalies were discovered which required further analysis.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

The lost southern enclosure and South Gate were both identified from fragmentary evidence and establishing the exact position and size of the original south wall presented a challenge. When reconstruction began there was little information on this wall except a projection of the line of the southern colonia wall. This placed the south wall slicing through the Lucy Tower motte – a relationship which did not seem likely. However, recent work on this part of the motte during a programme of banks stabilisation provided more information. A substantial medieval masonry wall measuring 3m wide and traversing the Lucy Tower motte west-east was revealed. The wall is probably founded on the Roman wall indicates the motte may have been constructed against it, flattening its southern side.

The reconstruction provides a sense of where concentrations of occupation were; around East Gate and Observatory Tower, the Lucy Tower, the Great Hall and around West Gate. With the discovery of South Gate it is easier to appreciate how these areas were autonomous. Other areas within the castle, particularly the western side, are presented as large open spaces; without further investigation these zones cannot be reconstructed easily.

The Lucy Tower, sat upon on an enlarged motte, can now be shown with its original east and west chamber blocks, internal ranges and window overlooking the city. With the tower, wing walls and South Gate, these formed a discrete enclosure.

Detail on the form of the Observatory Tower in the late 12th century can also be added. The tower is shown as a gaol tower which replaced a predecessor developed by Earl Ranulf during the Anarchy, later commandeered to become the county gaol. A stone ‘skirt’ around the base of the motte and a motte ditch were found and formed a hard circuit detaching the gaol from the rest of the castle.

The reconstruction will be made available across a range of media. The analytical process and collaboration with Pighill Illustration provided an opportunity to translate the archaeological study of the castle into a tangible representation. It enables the results of the research programme to be conveyed to a wide audience and goes hand-in-hand with the publication of a book about the Lincoln Castle Revealed Project in July 2021.