As the Castle Studies Trust funded part of the project to learn more about Raby Castle comes to a close, the funding of the digital modelling of Raby’s exterior, the castle’s curator, Julie Bidescombe-Brown explores what they have found so far which includes a short preview of the model in its glory.

Throughout 2022, the team at Raby Castle has been working with Durham University Archaeological Services on a project funded by the Castle Studies Trust to drone scan and create a digital 3d model of the entire castle exterior. At the project draws to a close, Raby’s Curator Julie Biddlecombe-Brown reflects on the work undertaken over the last year, including both the planned outcomes and unexpected benefits of the work undertaken.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

‘At the time of writing this blog, I am waiting with bated breath for an email that marks the end of a truly game-changing project for Raby Castle. The email will include the final embedded link to a detailed digital model of Raby Castle’s exterior produced over a series of drone scans during the summer months of 2022. The sneak preview given to the castle team was breath-taking. When we applied to the Castle Studies Trust for support for the grant I had no idea of the level of detail that the technology now enabled. My initial application for funding was based on the creation of a digital model that could be used as the basis for future interpretation; a tool for presenting the castle to new audiences. What we have achieved has ended up to be so much more.

For those not familiar with Raby Castle, this beautiful building in the south of County Durham has remained the family home of the Vane family for almost 400 years. Harry Vane, twelfth Baron Barnard is the current owner and along with his wife, Lady Kate Barnard, has set out ambitious plans to ensure the future sustainability of the castle and wider estate. This project reflects their vision, setting out to better understand the estate so that responsible stewardship of rich heritage assets can see the castle enjoyed and studied by future generations.

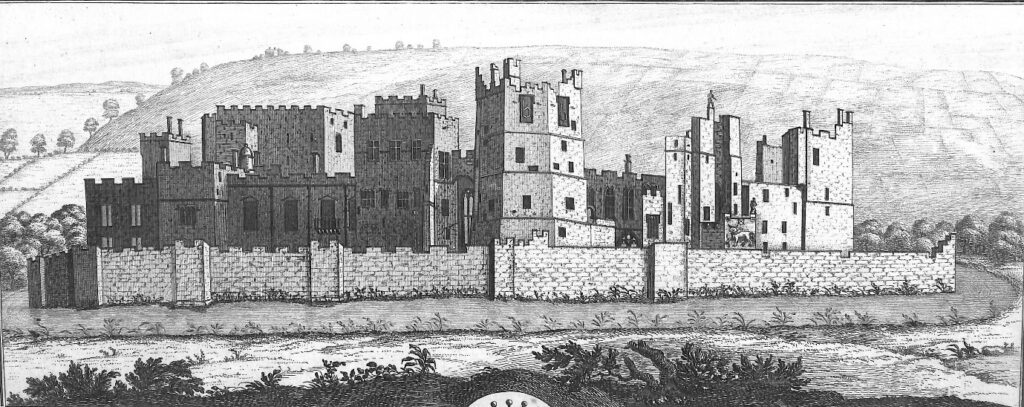

Going back to the castle itself: from the exterior, it is one of the most intact 14th century castles in the north of England, adapted over the centuries to provide luxurious accommodation for the two families who have lived here. First, the medieval northern powerhouse of the Neville Family who lost the castle after the failed Rising of the North. It was the Neville family who created most of what can be seen today, their license to fortify the castle having been granted by Bishop Hatfield of Durham in 1378. Second, the Vanes, later Barons Barnard, Earls of Darlington and Dukes of Cleveland came to Raby after purchasing the castle in 1626. Over two hundred years later, what remains the castle’s most comprehensive history was written by Catherine Lucy Wilhelmina Vane, the 4th Duchess of Cleveland, in 1870, a formidable scholar and biographer whose engaging narratives combine clear research of the sources available to her, with a delightful peppering of artistic license. Her handbook has also been a useful tool in this project, with descriptions of alterations, anomalies and observations that come with complete familiarity with a site. The Duchess clearly loved the castle and during the late 19th century welcomed guests from across the globe. Earlier generations of her husband’s family down-played the castle’s splendour. Courtier Sir Henry Vane, who bought the castle in 1626 twice received Charles I there; first in May, 1633; and again in April 1639. Charles is said to have been greatly struck by the size of the castle, and to have rebuked Sir Henry for speaking of it somewhat irreverently as a ‘mere hillock of stone.’ ‘Call ye that a hillock of stone? By my faith,’ said he, ‘I have not such another hillock of stones in all my realms.”

You can judge the latest capturing of ‘the hillock’ yourself, by viewing the model funded by this project. Available to the castle team in multiple formats, from a wireframe for digital manipulation to fully overlaid with photographs for a full ‘photo-real’ view, the scan has created a snapshot of the castle at a moment in time but helps us look backwards into its history and forward, securing its future. The Raby team is working with Heritage Interactive, sector AV specialists to adapt the model to be public facing and engage visitors with the story of the medieval fabric in a new introductory film that we will launch next year. But the model also gives us the potential to add to this; to explore later phases of development in the same way, to isolate, interpret and even digitally rebuild key features that have changed over time, such as the removal of the 14th century barbican in the late 18th century, creating the now slightly confusing Chapel Gateway, or exploring the remains of passages, staircases and windows that make no sense in the current configuration of the building.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

The base-line data has multiple benefits – in addition to creating new films, we are exploring 3d printing of a model of the castle in jigsaw puzzle-like sections for use with schools and other audiences – what better way to inspire a new generation of castle enthusiasts than to couple the challenge of a puzzle with a superb digital model? The level of detail will also be of huge benefit to the castle buildings team in monitoring condition, working in tandem with our conservation architects who can now view the fabric almost stone-by-stone. This will, we anticipate, not only help us to detect any building changes that might need attention but will also help us in master planning for the future.

A complimentary annex to the project, funded in-house is an archaeological report by Durham University Archaeological Services that will sit alongside the model. This collation and analysis of source material – including what we have learned about the existing fabric – has been led by Senior Archaeologist Richard Annis who over the course of 2022 has delved into every nook and cranny of the castle – peering under floorboards, climbing disused staircases and opening the door of every built-in cupboard to see what lies behind. This level of survey has never been done and when linked to the model, and an examination of known archival and other documentary sources compiled by a willing group of volunteers, we start 2023 with a far better understanding of this remarkable building than ever before. The report and model will be used together by the castle team including custodian, curatorial, archive and buildings teams, and of course our conservation architects as we care for and interpret the castle and will be available as a resource to scholars and academics, hopefully inspiring future research.

And of course, there is still research to be done! The project may have answered questions but has left us with many new ones. Over the coming months, or should that be years … we will continue to explore some of the puzzles of the building, from the origins of some of the towers, to vertical access routes. But what has changed over the last year is that we now have a superb data set as a starting point. Our thanks go to Archaeological Services Durham University and in particular Richard Annis for bringing their enthusiasm, skills, expertise and inquisitive minds to the project, and also, of course, to the Castle Studies Trust which provided us with the funding to enable it all to happen.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter