Little physically now remains of Holt Castle, however, one of the first projects the Castle Studies Trust was for leading buildings reconstruction artist Chris Jones-Jenkins and the late and much missed Dr Rick Turner to digitally reconstruct the castle using a mixture of historical sources and recent archaeological excavations to bring the castle back to life with a series of images and a video fly through. Here, in a piece first published in History Extra in 2015 explains how it was done.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

History:

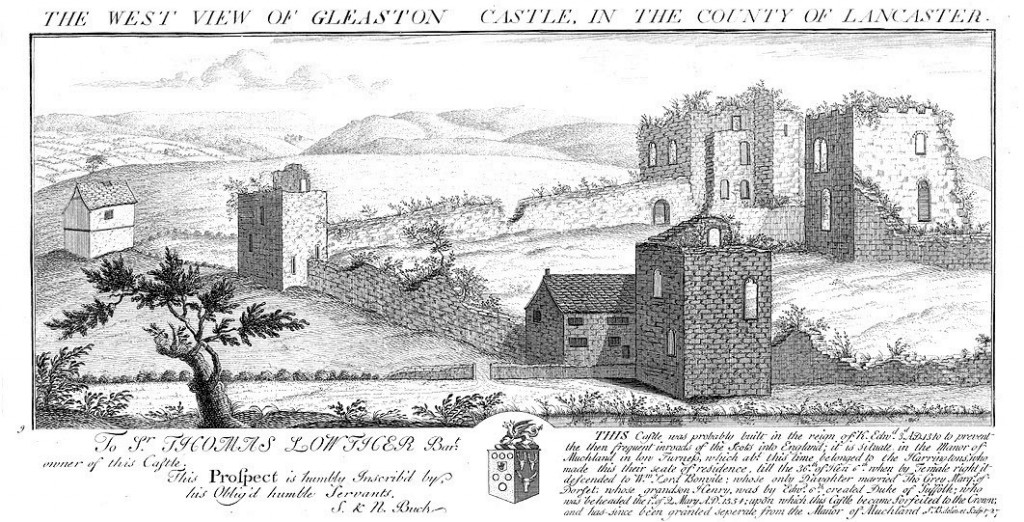

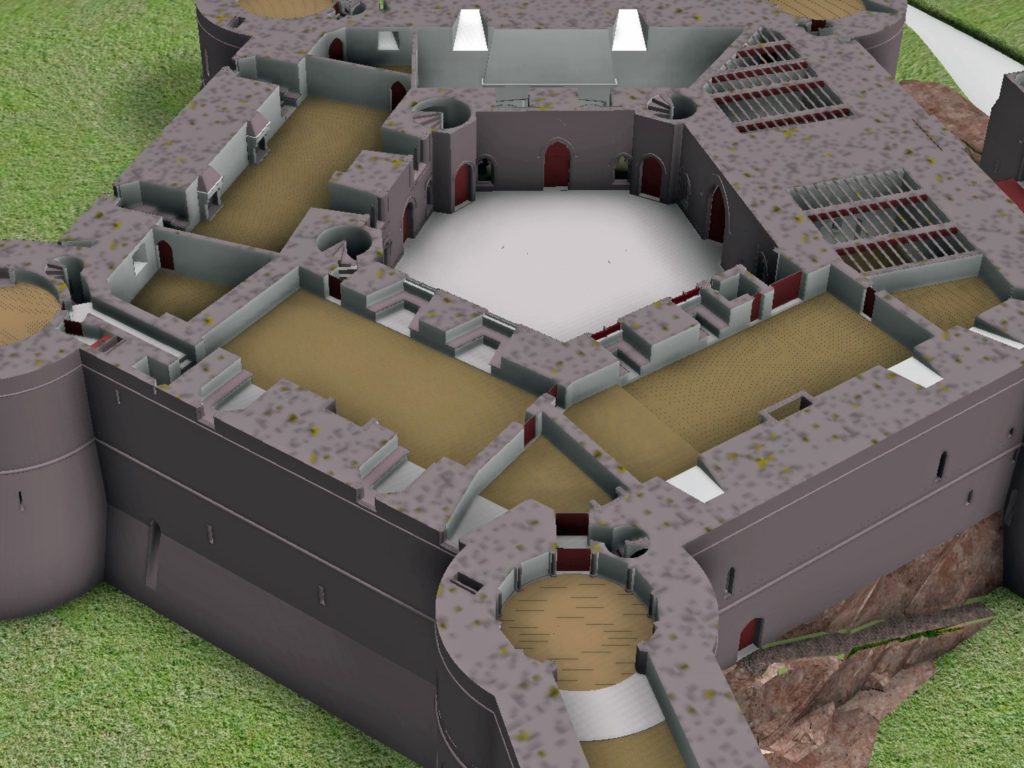

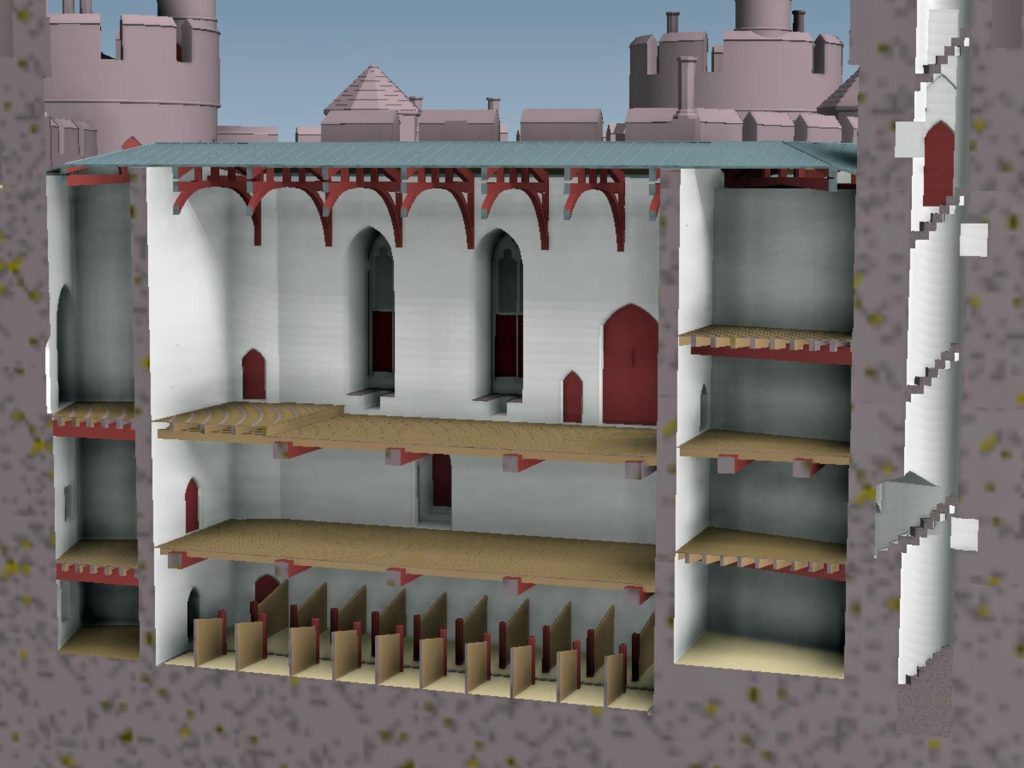

To secure his conquest of north-east Wales, Edward I created five new Marcher lordships in 1282, and gave them as reward to his political allies and close friends in recognition of their loyal service. The lordship of Bromfield and Yale was granted to John de Warenne, sixth earl of Surrey (1231-1304). It is not known when he started building Castrum Leonis or ‘Chastellion’ as Holt Castle was known in the Middle Ages. The castle is first referred to in 1311 some years after it was probably completed. Warenne’s master mason chose an open and relatively flat site above the west bank of the River Dee, close to one of the ferry crossings into Cheshire. This allowed him to create a symmetrical pentagonal castle with a tall round tower at each corner, and the main rooms ranged around an inner courtyard. There were up to three storeys raised above the original ground level, with the moat and up to additional three basement levels cut down into the sandstone bedrock. It was a revolutionary design and was one of a group of similar architectural experiments being undertaken by the other new Marcher Lords at castles such as Denbigh, Ruthin and Chirk. At all these sites geometrical complexity, architectural grandeur and the provision of well-appointed accommodation seemed to be more important than their defensive capabilities.

The sixth earl was succeeded by his grandson John, the seventh earl of Surrey (1286-1347). Described by Alison Weir as ‘a nasty, brutal man with scarcely one redeemable quality’, he was involved with the political upheavals of Edward II’s reign, including the loss of Holt Castle for a time to Thomas, earl of Lancaster. This John died without a legitimate heir, and Edward III intervened to settle his estates upon Richard FitzAlan, third earl of Arundel (c.1313-1376). His son, Richard the fourth earl (1346-1397) was one of the ‘Lords Appellant’, who had curbed Richard II’s powers and had the king’s closest allies executed or exiled during the ‘Merciless Parliament’ of 1388. It took nine years before the king was able to wreak his revenge on these powerful men. Arundel was brought to trial for treason at Westminster on 21 September 1397, and was convicted and beheaded on the same day. Richard II seized his estates and incorporated Bromfield and Yale into his new principality of Cheshire, with Holt Castle as its main stronghold. Building work was commissioned in 1398, which saw the Chapel Tower extended and included a water-gate, called ‘Pottrell’s Pit’ in later documents, linked to the river. Over the next year more than £40,000 in coin, jewellery, gold and silver plate was transferred from the royal treasury in London to Holt for safe keeping. When Henry Bolingbroke – later Henry IV – returned to England in 1399, he shadowed Richard II up the Welsh Marches and was quick to recapture Holt Castle. Despite being defended by 100 men-at-arms and being well provisioned, Henry’s men, including the French chronicler Jean Creton, were able to enter through the new water-gate and ascend ‘on foot, step by step’, to take the castle unopposed and so recover this vast proportion of the king’s disposable wealth.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Over the next 139 years, three more owners or stewards of the lordship of Bromfield and Yale were to be executed for treason. The first was Henry Stafford, second duke of Buckingham (1455-83). A year after his death, Sir William Stanley (c.1435-1495) acquired the lordship from Richard III. Despite his role at the Battle of Bosworth which brought his relative Henry VII to the throne, he was implicated in the Perkin Warbeck affair and was executed in 1495 after which Holt Castle reverted to the Crown. The last of this group was William Brereton (c.1487×90-1536) who was appointed steward of the castle where he held ‘great porte and solemnities’, before he was convicted of adultery with Anne Boleyn and beheaded.

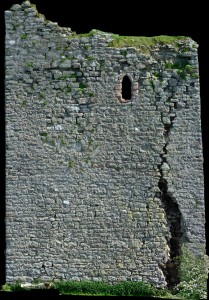

Holt Castle remained the property of the Crown and was to form part of the estates of the Princes of Wales. It was held for the king during the Civil War and in the 1670s, the buildings were sold off to Sir Thomas Grosvenor, who systematically dismantled nearly all the fabric and transported it to help in the building of his Eaton Hall, a few miles south of Chester. This has left us with the stump of rock and walling which survives today.

Reconstructing the Castle:

Two attempts have been made to understand the original the former appearance of Holt Castle: by Alfred Palmer in 1907 and Lawrence Butler in 1987. They had access to plans and views of the castle drawn in 1562 and 1620. The problem they faced was that these two sets of drawings are contradictory and they were hard to relate to what survived. Since 1987, new evidence has been made available:

- Documentary evidence for Richard II’s building work.

- The publication of a transcript of the Holt Castle inventory taken after Sir William Stanley’s arrest in 1495.

- The discovery of a new early-seventeenth century plan of the castle in the National Library of Wales.

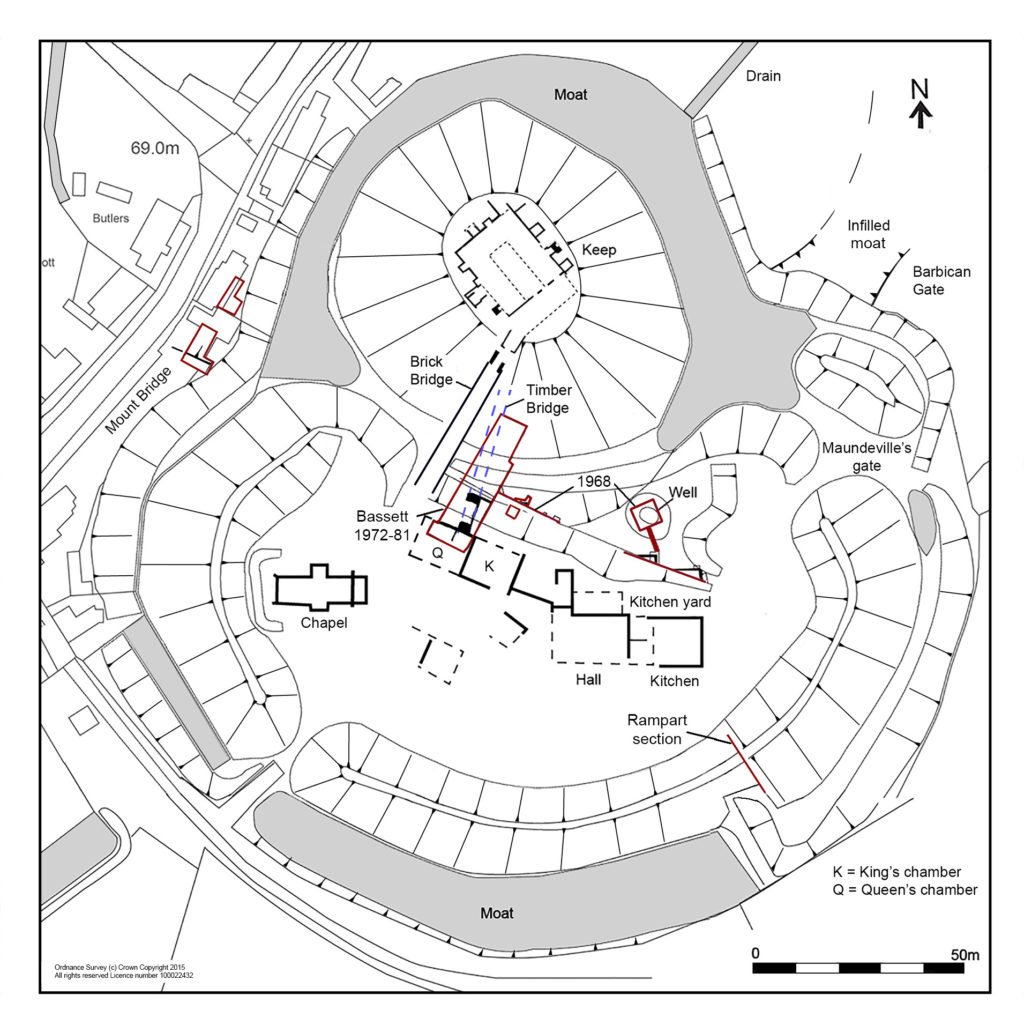

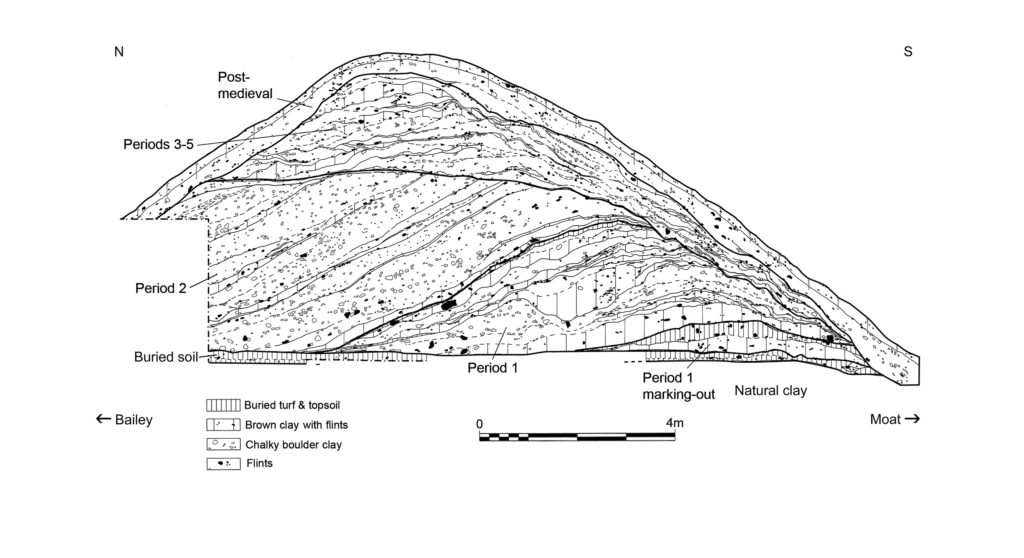

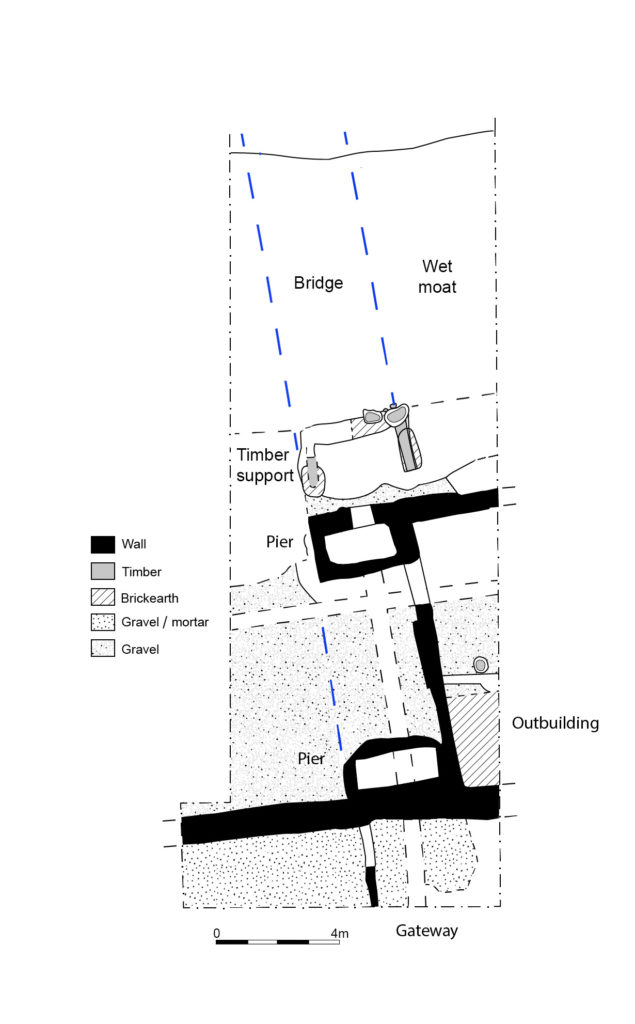

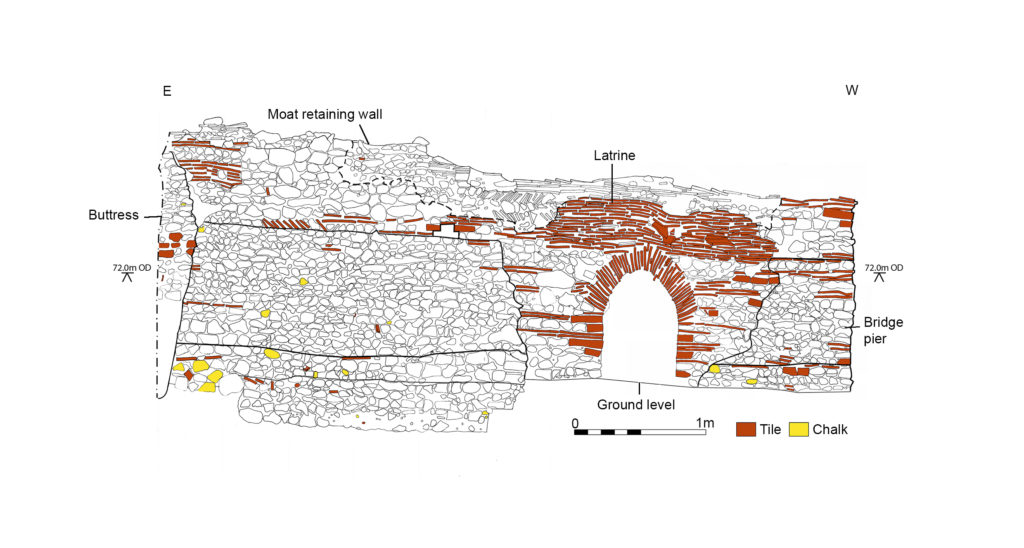

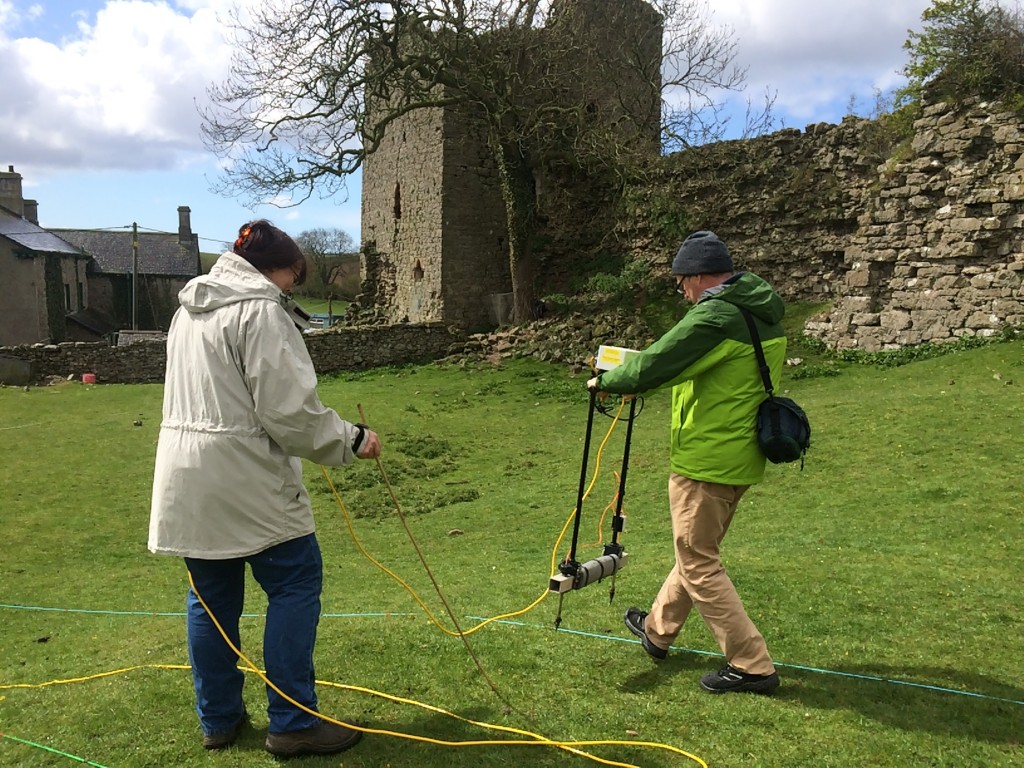

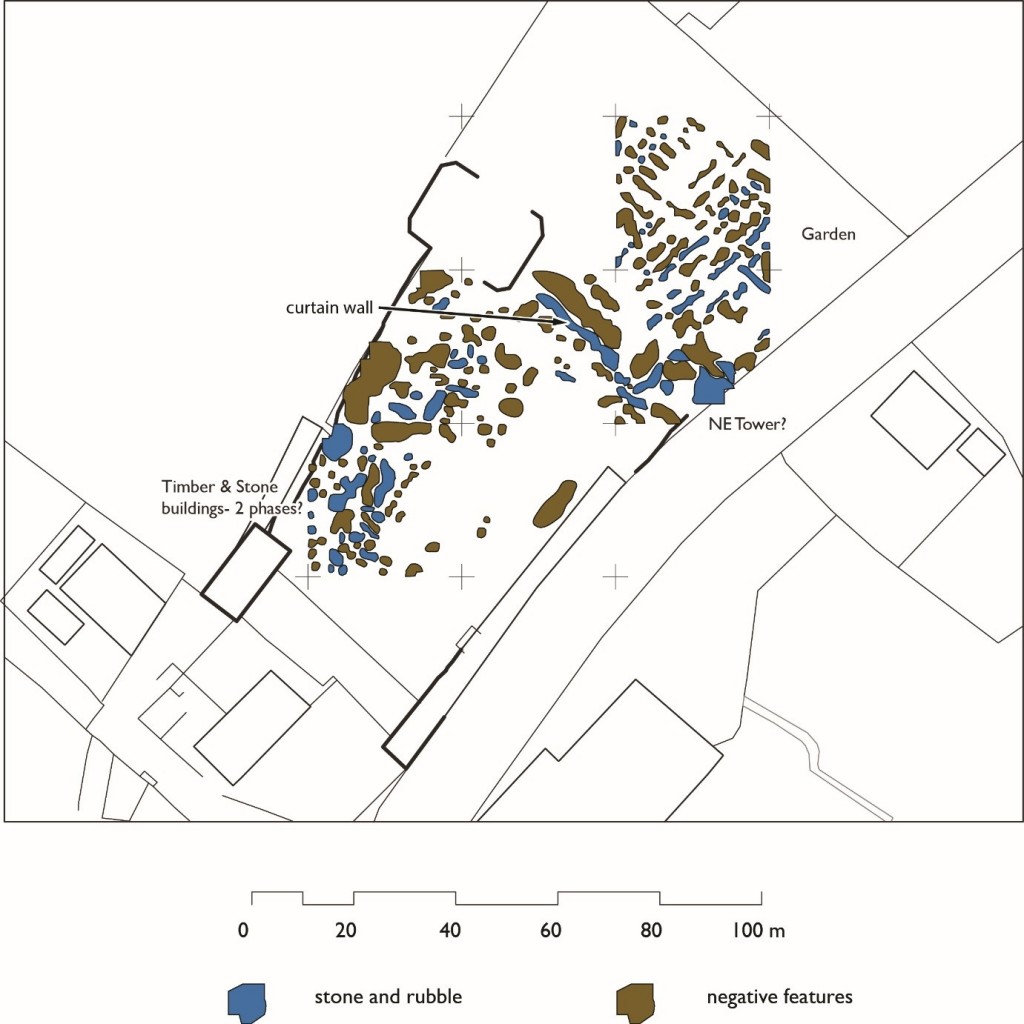

- A programme of masonry consolidation, archaeological excavation and survey led by Steve Grenter, Wrexham County Borough Council, in partnership with the Holt Local History Society.

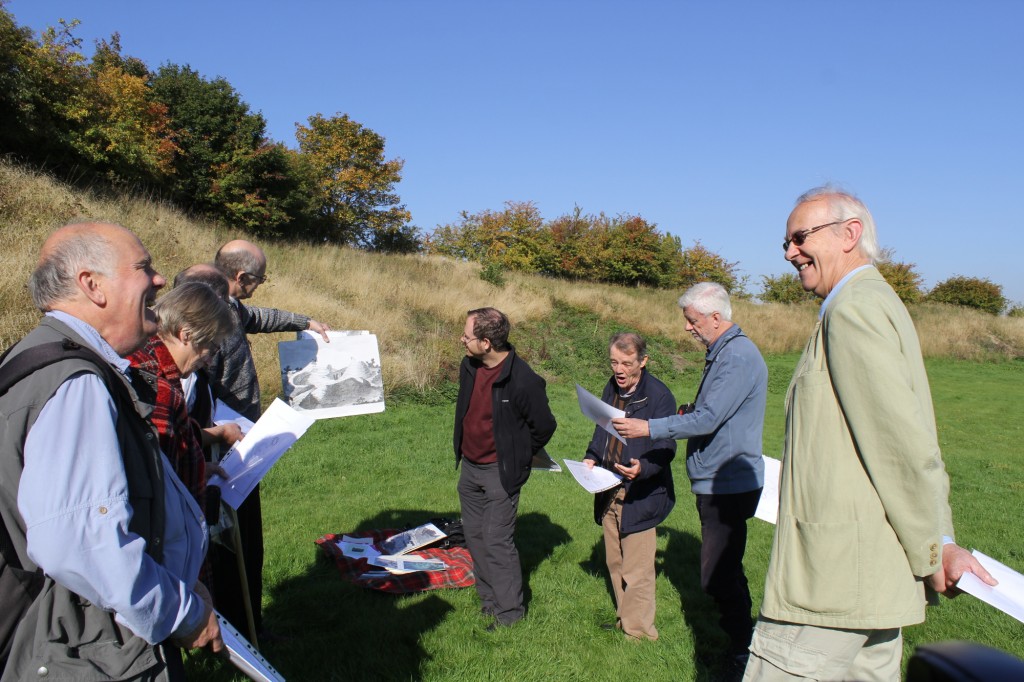

This new work prompted me to undertake another attempt to reconstruct Holt Castle. With the help of a grant from the Castle Studies Trust, I was able to commission the well-known castle reconstruction artist, Chris Jones-Jenkins, to develop a 3D digital model which was flexible enough to capture and assimilate the new data and modify the structure as new insights were gained.

The challenge has been to weigh each source of evidence and identify which strands should have precedence when contradictions emerge. A hierarchy was developed:

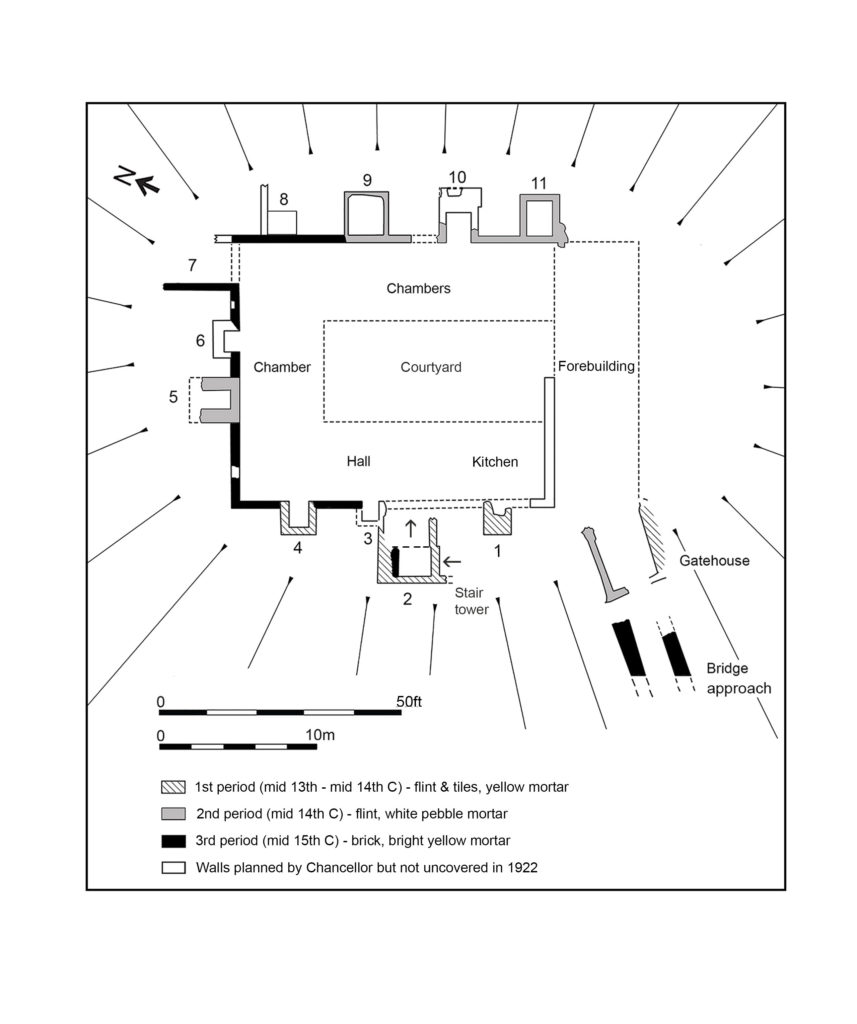

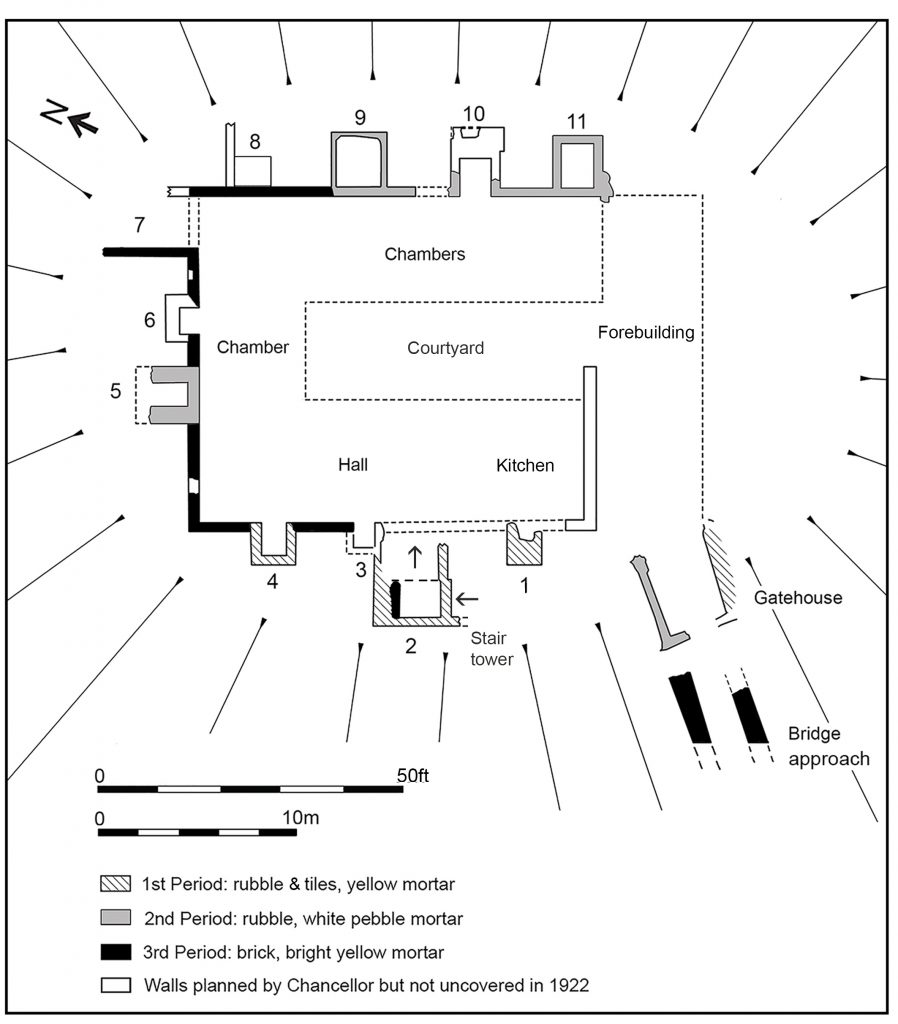

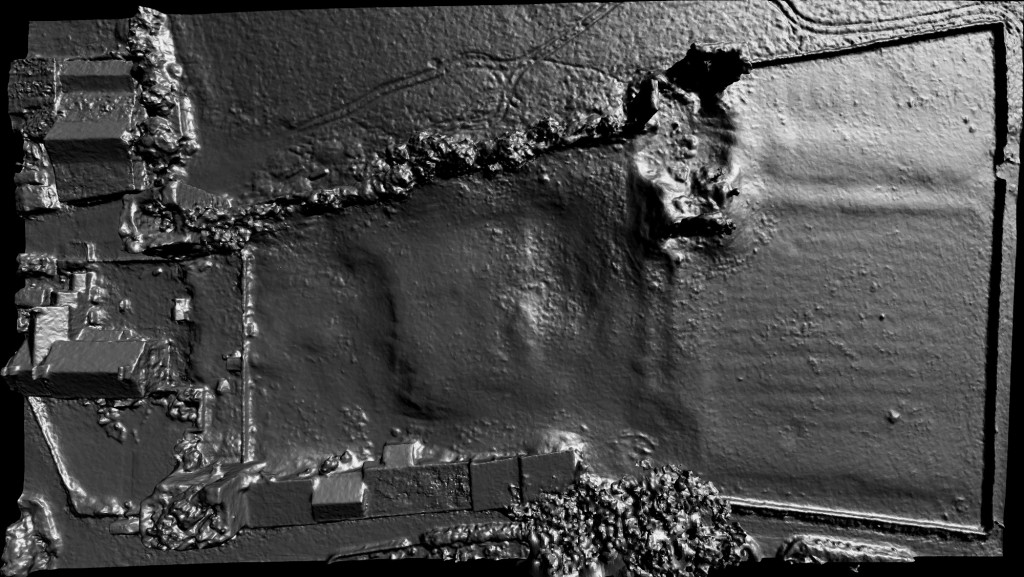

- The visible masonry of the castle and the modern topographical survey of the site provided the primary terrain model on which the remainder of the castle was constructed.

- The archaeological evidence for the rock-cut footings, the bases of three of the towers and the line of the channel leading into the water-gate provided other fixed points in the model.

- By considering the content and the potential reasons for the drawing of the three, early-modern ground plans and the two associated views, that of 1562 was assessed to be the most reliable for the details that it showed, the early seventeenth century plan for its dimensions, and those by John Norden of 1620 to be the most inaccurate, despite them being the ones most frequently published.

- The list of rooms and the route followed by the appraisers of the 1495 inventory provides the most comprehensive source for the internal layout of the castle. However, it became clear that those rooms without contents, such as the triangular ante-rooms to the towers and the latrines, were not listed.

- None of the views of the castle were architecturally detailed, and none showed all of the exterior or much of the inner courtyard. This information had to be derived from surviving details from other Edwardian castles in North Wales or from work undertaken in Richard II’s reign, when considering the projection from the Chapel Tower.

The development of the model became an iterative process between the historian and the artist. Different combinations of layout and floor heights were tried, building on the fixed points surviving at basement level and rising up in an effort to accommodate all the rooms. Suites of accommodation began to emerge. Sir William Stanley’s great chamber led off the high end of the hall and controlled access in one direction to his counting house and the chapel, and in the other to the Treasure House and the High Wardrobe, where all the valuables were kept. Across the courtyard his wife, Elizabeth, had her own great and bed chamber, linked to the nursery. Above her accommodation was a chamber for her gentle women, well away from the yeomen’s dormitory under the lord’s great chamber. One range was dominated by the kitchen, rising the full height of the castle, connected at basement level to a larder, pastry house, well house and a wine cellar on one side and offices for the cook and butler on the other. As was normal the constable had a suite over the inner gate, but unusually a stable for 20 horses was created in a basement below the hall with access for the animals across the moat and up a ramp into the castle.

Working on this reconstruction, our admiration only grew for the original designer. He created a symmetrical plan and external appearance but produced complex internal arrangements to meet his patron’s needs. Holt is as much a chivalric ideal as a practical castle. An animation of the reconstruction of Holt Castle has been produced by Mint Motion of Cardiff and can be viewed here:

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Feature image courtesy of Wrexham Borough Council