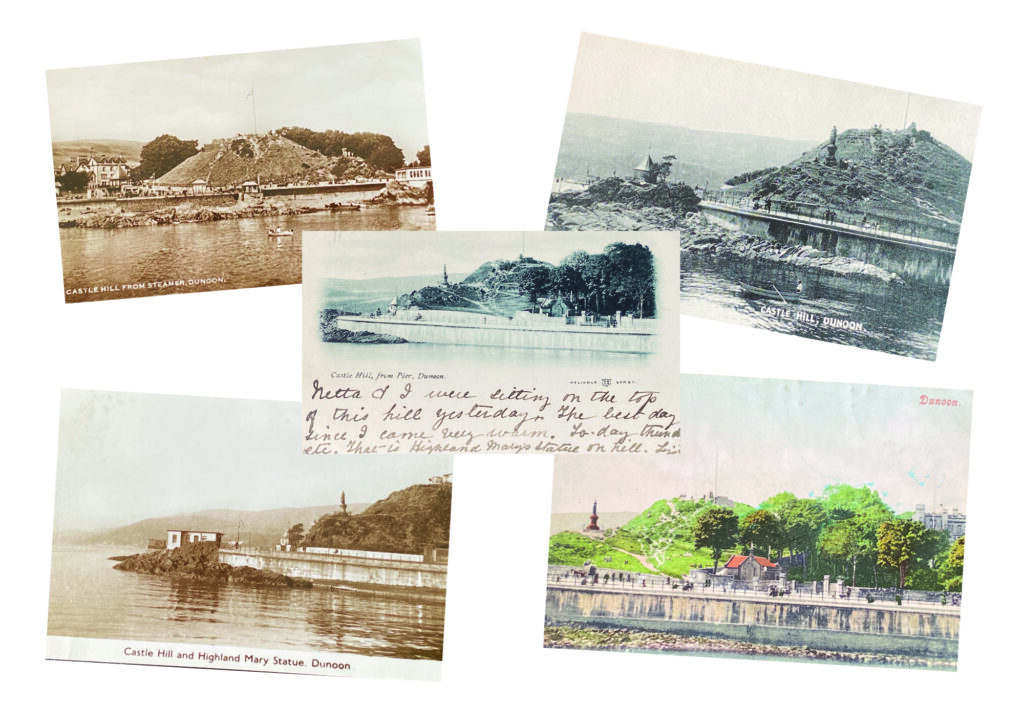

In her final blog piece (for now) Project Lead, Sophie Ambler, looks back at the three excavation at Lowther

The on-site investigation of the medieval castle and village at Lowther (Cumbria) has now drawn to a close. Over the past month, a team from Allen Archaeology, UCLan, and Lancaster University has been exploring the site through geophysical surveying, excavation and archival research. We now have a geophysical survey of the village to analyse alongside LiDAR and the original earthworks survey. Over the coming months, our small finds will be analysed, together with soil samples, in the hopes that they yield dating evidence, and a report will be prepared drawing together the results from our trenches.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Meanwhile, we have the chance to reflect on what’s been a thrilling month of investigation.

Uncovering the construction of the ringwork castle and assessing its situation has helped us to get a sense of the site’s place in the broader landscape. Since the area in which the castle stands is now wooded, this takes some imagination.

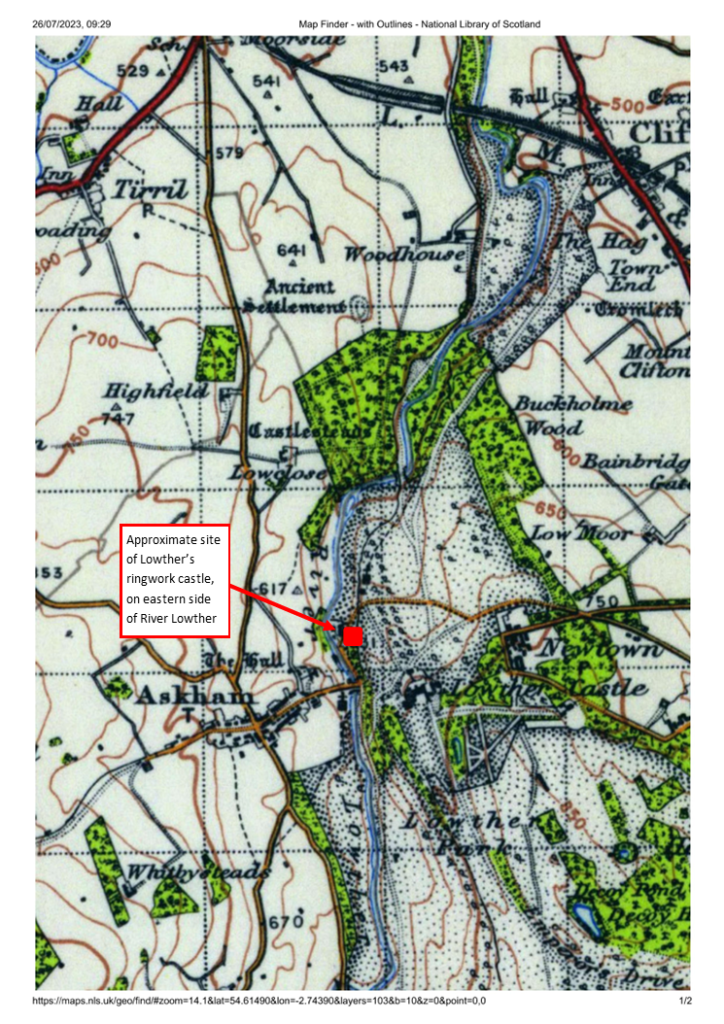

The ringwork castle is sited on the edge of Lowther’s western escarpment, which runs down to the River Lowther. The ringwork’s positioning is clearer in OS maps (image 1), where its proximity to the river and the steepness of the escarpment are evident. Today, one can get some sense of the impact of this positioning by heading eight hundred metres or so south to take the view over the escarpment from the Jubilee Summer House, in the grounds of the nineteenth-century castle (image 2, and view the panorama on Google Maps.), although the escarpment is far less steep here. Originally, the castle would have commanded wide-ranging views to the west, across the river to Askham Fell, and would have been a highly visible – perhaps dominant – landmark for miles around.

The scale and the construction of the ringwork castle has also become clearer. Again, given the tree coverage and overgrowth, it’s long been hard to perceive the earthwork’s size and form. It’s been hard also to capture the earthwork in photographs – but throughout the project Lowther’s resident photographer, Tony Rumsey, has been busy. His drone footage gives a much clearer sense of the site (image 3). To the top of the picture, the western escarpment drops steeply down from the earthwork to the river. In the foreground, Trench Two cuts into the earthwork’s northern bank.

The image also shows how the floor level of the earthwork’s interior is significantly higher than the exterior ground level. As Trench Two revealed, the ringwork was constructed as a large, roughly square mound with layers of earth and stone, with its banks built up further to gird the mound. Meanwhile, the interior was topped with a metalled surface. We expect that the banks would have been surmounted by a simple fence or palisade (Trench Two did not reveal any postholes to indicate this palisade, but this is not surprising given that the top of the bank has almost certainly been lost to slippage).

The metalled surface covering the interior of the ringwork is also clear in Trench Four (image 4). This trench takes in the approximate area of the ringwork castle’s entranceway, which cuts through the eastern bank. The entranceway may have included a wooden gateway, although we haven’t found firm evidence of one in Trench Four, and perhaps would need to open a larger area to be sure. Trench Three picked up a trackway (image 5), noted in the earthworks and geophysical surveys, which linked village to castle and brought visitors to the entranceway.

One of the highlights throughout the project has been welcoming visitors to the site. The project’s archaeology students from UCLan have been giving tours to those who’ve ventured down to the site during the course of the dig, keen to know more about what we’ve been uncovering. On Saturday 15 July, we were delighted to welcome representatives of the Castle Studies Trust and share with them our ongoing work (image 6), as well as members of several regional history and archaeology societies. We also had a visit from Professor Alice Roberts and the team from BBC2’s Digging for Britain (image 7), who plan to feature the project in their next series.

We still have further to go in analysing our findings and expanding our investigation of Lowther’s medieval castle and village, but are very pleased with how the on-site phase of our project has gone – not only in exploring the remains of an important medieval castle site, but also in training a new generation in castle archaeology, and encouraging public appreciation of castle studies. The project team is extremely grateful to the Castle Studies Trust for funding the project and for its support throughout, and would also like to thank the Lowther Castle and Gardens team for their help and hospitality over the past month. I’d also like to say a huge thank you to the indomitable Jim Morris, who has led the UCLan archaeology contingent, the hardworking and dedicated cohort of UCLan archaeology students, and the excellent Allen Archaeology team (Jonny Milton, Rob Evershed and Tobin Rayner).