In part three of our dig diary, project lead Sophie Ambler talks about another type of digging, not of holes in the ground by through the archives to discover what if any historical evidence there is for Lowther.

Whilst the archaeologist are at work on site at Lowther, I’m attempting to piece together the site’s history from the documentary evidence.

Our biggest challenge is tracing the origins of Lowther’s medieval castle and village, which we think date to the late eleventh or early twelfth century. For most of England, historians have a phenomenal source for settlement in the eleventh century: Domesday Book. This was William the Conqueror’s enormous survey of landholding, compiled in 1086. It gives various details, settlement by settlement, such as landholders, land under cultivation, notable buildings and households (for an introduction to Domesday and the latest research, listen to this BBC History Extra podcast by Professor Stephen Baxter). Domesday thus helps historians to trace the process by which the Normans conquered England over the twenty years from 1066.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

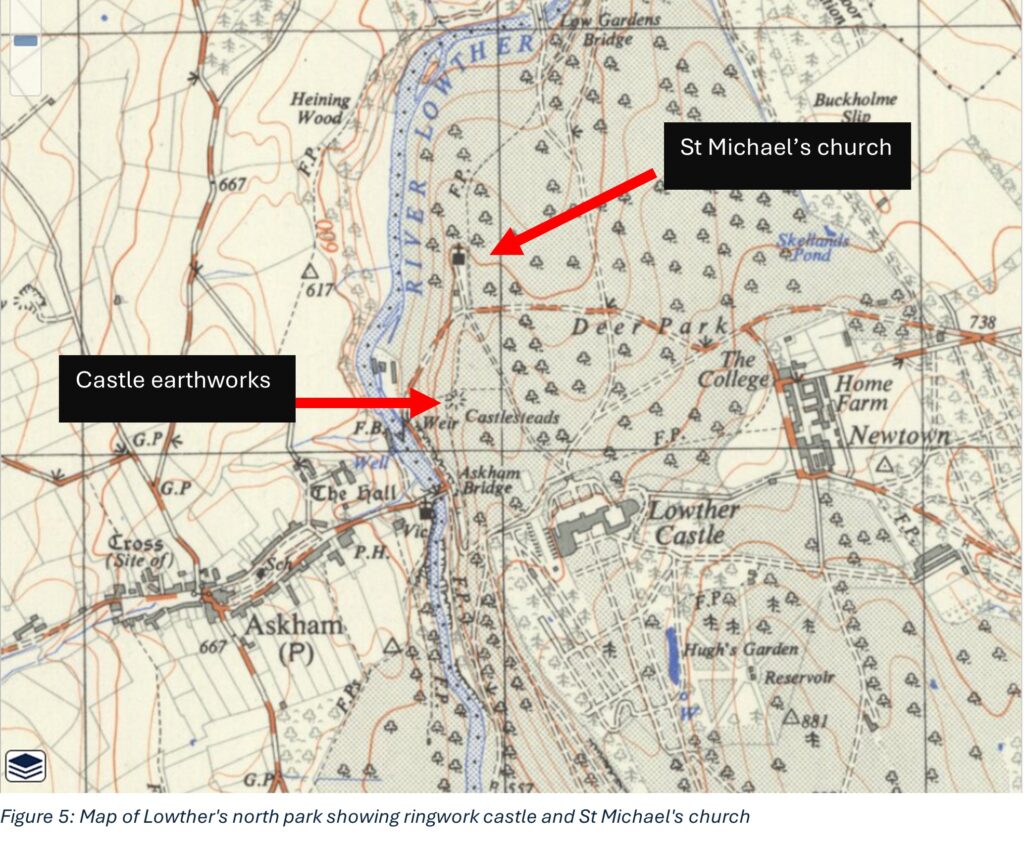

Frustratingly for us, the area of modern Co. Cumbria doesn’t appear in Domesday Book. Because this region wasn’t conquered by William I, it found no place in the Domesday survey. As discussed in our project’s first Dig Diary entry, the region was only conquered in 1092, by William the Conqueror’s son, William Rufus. The Anglo-Saxon chronicle states that William Rufus, following his campaign of conquest, ‘sent many peasant people with their wives and cattle to live there and cultivate the land’. This was, effectively, a process of Norman colonisation. We’re hypothesising that the ringwork castle earthwork and village at Lowther date to this era.

What was this region like when the Normans arrived in 1092? Here, historians have worked hard from patchy evidence for the Kingdom of Cumbria in the tenth and eleventh centuries. This was a Brittonic kingdom (distinct from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the south) but, as Professor Fiona Edmonds has described, parts of the kingdom were ‘multi-lingual and multi-cultural’ (including settlers we might think of as ‘Vikings’ and their descendants). These groups were encompassed by the term ‘Cymry’ (‘inhabitants of the same region’), from which the names Cumbria and Cumberland derive.

Who were the settlers dispatched in 1092 by William Rufus to colonise the Kingdom of Cumbria? There’s no hard evidence, but Dr Henry Summerson has suggested (in his book Medieval Carlisle) that they hailed from Lincolnshire. This theory has found some support from the late Professor Richard Sharpe, although he noted that evidence for a Lincolnshire connection dates to around 1100, so may represent a second wave of settlement.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

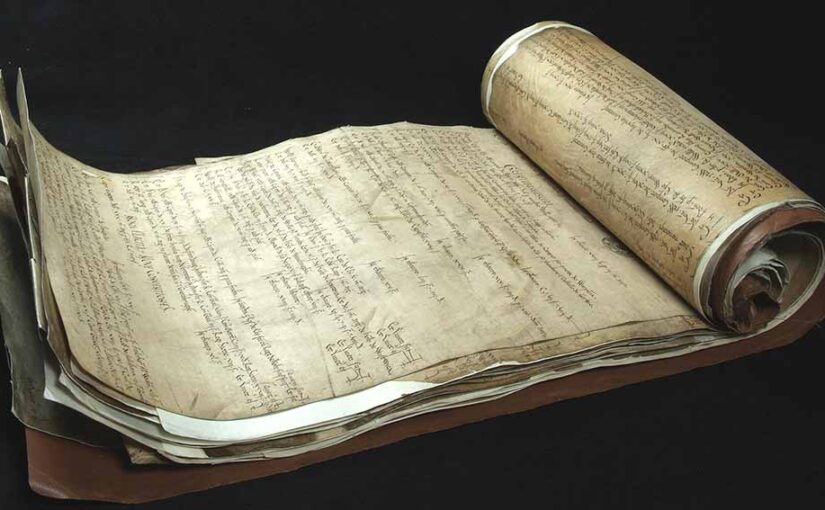

Our first major evidence for Norman rule of the region comes in 1130, under King Henry I (William Rufus’ brother). This is found in a Pipe Roll – a record produced by England’s central government detailing the Exchequer’s annual audit, so-called because the parchment membranes were sewn together at the top and rolled up to look like a pipe (read more on the Pipe Roll Society website). The first surviving Pipe Roll dates to 1130. Professor Sharpe used this and other evidence to reconstruct the early Norman administration of the region. He concluded that the Normans formed the shires of Cumberland and Westmorland out of the old Kingdom of Cumbria by 1130, and were administering these shires under the aegis of central government. Even then, however, both counties were run ‘as a territorial unit’ rather than shires proper, overseen by an administrator rather than fully-fledged sheriffs. (You can read Professor Sharpe’s analysis in full here). This is perhaps not surprising, given that in southern England the Normans could co-opt the governmental systems of the Anglo-Saxon state, including shires and shire courts. Cumbria was a different beast.

Is this all to say that written evidence can’t tell us much about the Norman conquest of Cumbria in general, or about our site in particular? Yes and no. It does highlight the importance of archaeological investigation in filling the gaps in written evidence – and suggests how findings from the Lowther Castle and Village project could be significant to both historians and archaeologists in tracing the process of Norman conquest and colonisation and its realities on the ground. On the other hand, we do have written evidence for the Lowther site dating from the thirteenth century onwards, which we can use together with the archaeology to trace the site’s biography. More of this in a forthcoming post!

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Follow the project on Twitter via the hashtag #LowtherMedievalCastle.