Post graduate student Tom Davies explains how he has taken some of the latest civil engineering techniques to help understand the condition of the stone work of old buildings, using Durham Castle as a case study.

Durham Castle was the building of interest for my master’s research project in 2023/4. Durham Castle has an incredible history, being founded in 1072 on the orders of William the Conqueror, to being the seat of the Prince Bishops, to now being part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site and University College for Durham University. The Castle’s rich history and architectural significance makes it preservation crucial, ensuring that its historic features are maintained for future generations.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

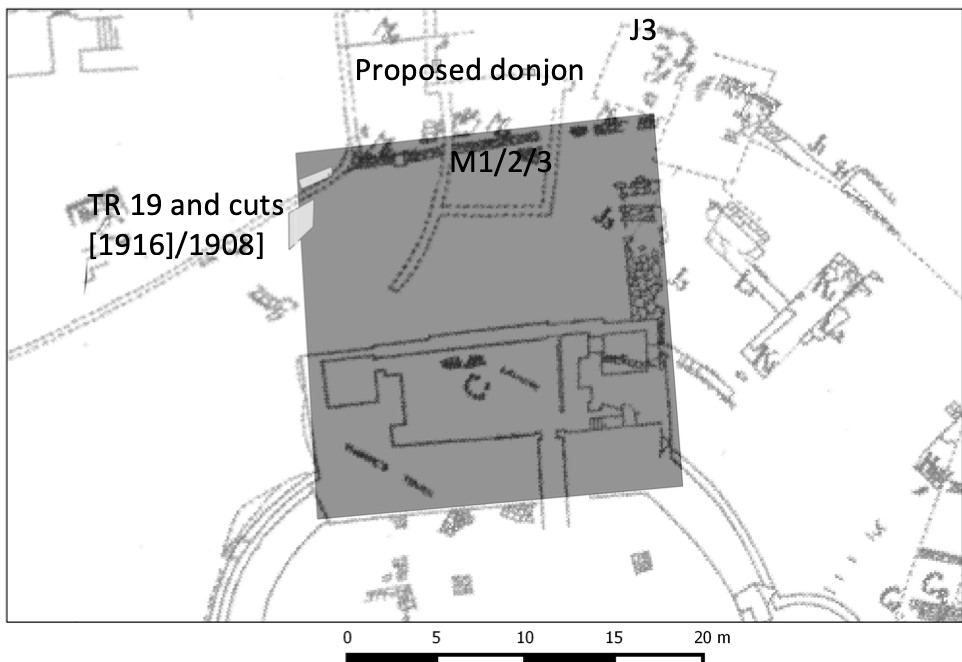

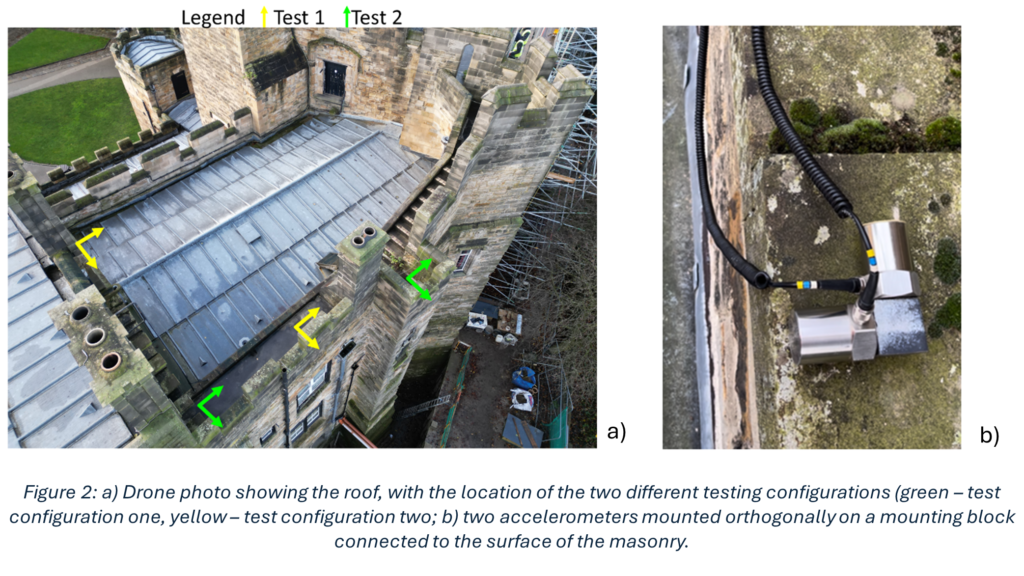

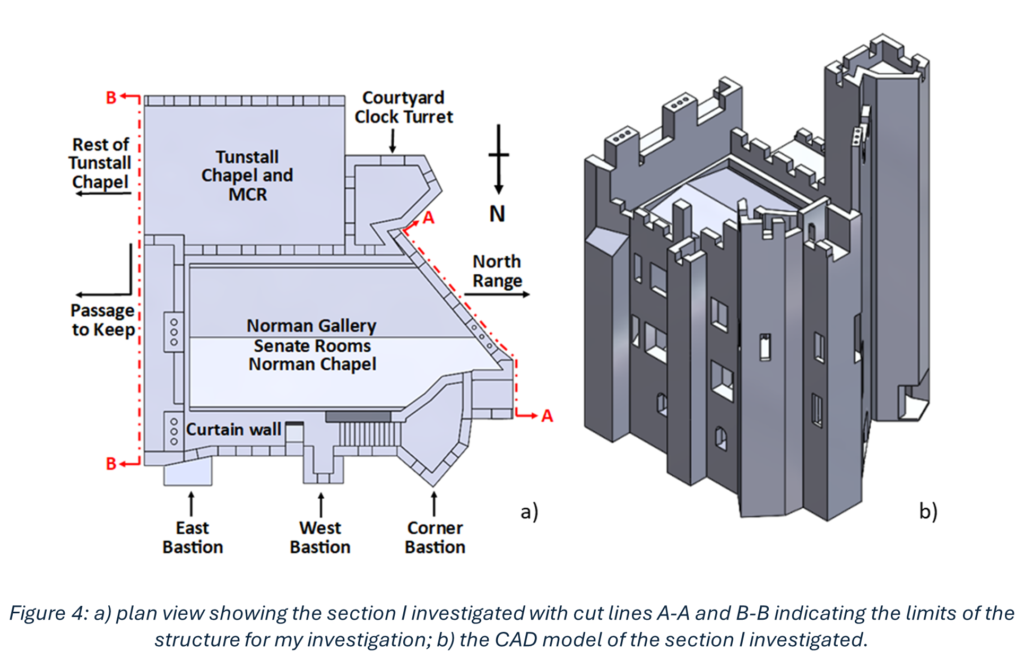

My research was based on understanding how a section centred around and above the Norman Chapel, the oldest building in County Durham, behaves under ambient excitation. Every structure experiences ambient excitation under normal operating conditions, it is the study of how a structure moves due to natural stimuli such as how it reacts to windy conditions and how it responds to when people move through the structure. Within the section I investigated, the Norman Chapel was on the ground floor, the Senate Rooms on the first floor, and some of the rooms of the Norman Gallery were on the second floor, with the roof above. These spaces, along with their remarkable examples of Norman architecture, make the conservation of this part of the Castle especially vital. The first non-destructive in situ testing I conducted was ambient vibration testing. This involves using multiple accelerometers in orthogonal directions (at right angles, seen in Figure 2) to record how the structure responds to ambient excitation, in this case measurements were undertaken on a windy day. Every building vibrates naturally at its natural frequency, which is determined by the building materials and structural connections of the building among other conditions. The taller the building, the lower the natural frequency, as they are more flexible. The Castle section I looked at is 3 storeys high, so one would expect a higher natural frequency than that of a structure such as the main tower of Durham Cathedral, which is 66m tall. The recorded accelerations were converted into frequency measurements which revealed information about the natural frequencies. This conversion is important, as when plots are made, it is possible to see different modes of vibration.

In order to characterise the masonry parameters that were used in the numerical model and subsequent simulations, another type of non-destructive in situ test was performed, sonic tests. Some tests were undertaken within the Norman Chapel, as this is the oldest part of the Castle, and its masonry has therefore been subject to the most deterioration of any internal section of the Castle due to its age. Additional tests on a masonry panel in a Gallery (corridor) just outside the Norman Chapel were conducted, this is because this Gallery is a very similar age to the masonry of the rooms above the Norman Chapel, from around the 1600s. From this, the different ages, and therefore state of deterioration, of the masonry within the Castle could be included.

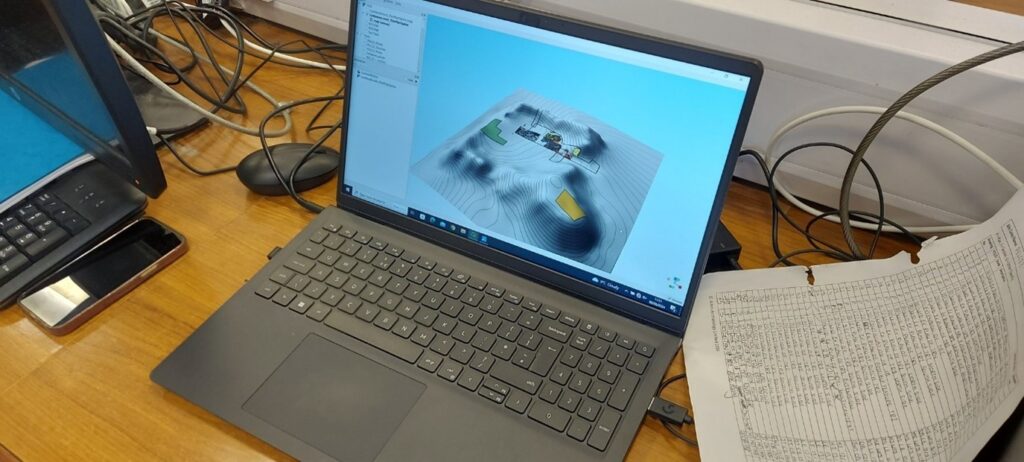

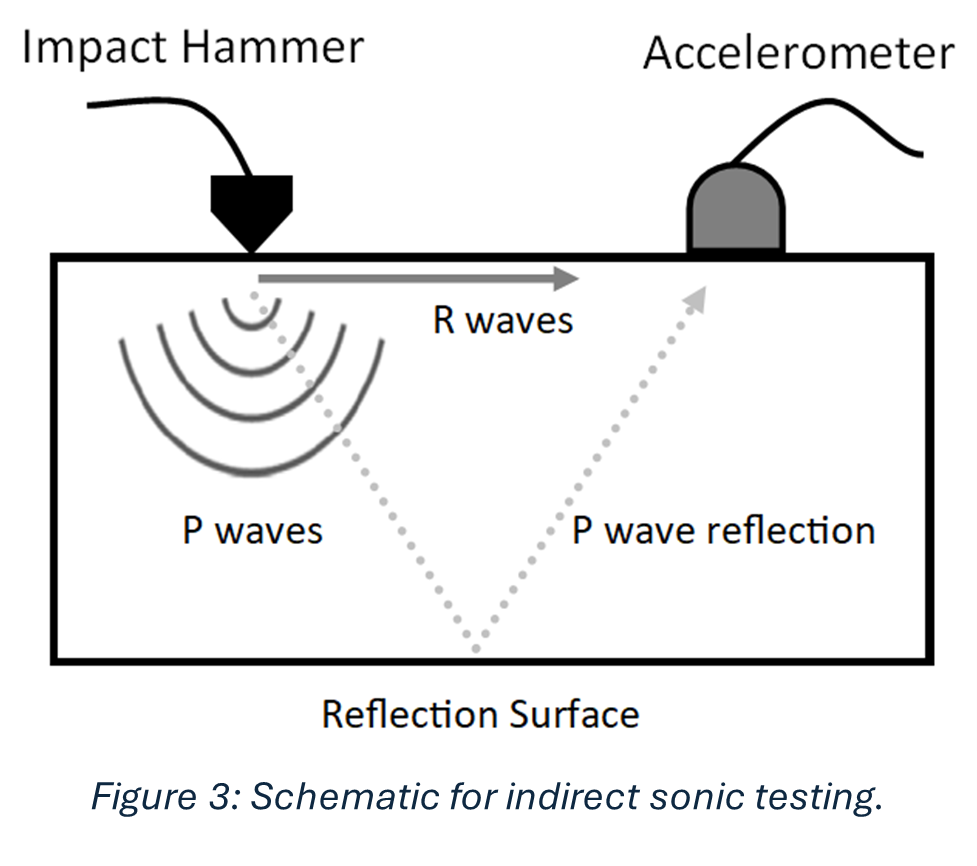

Sonic tests involve hitting the masonry, gently, with an instrumented hammer, shown in Figure 3, and recording the time it took for the subsequent waveform to be registered on an oscilloscope (a machine that shows waves) connected to an accelerometer. Figure 3 shows how this process works, there are two types of waves: P and R waves. The main difference is one travels along the surface of the stone, and the other travels into the stone and reflects off the back of it and returns to the surface. I will focus on the P waves (their names are quite confusing, but it is interesting to know that you can obtain the desired outcome, here the determination of material properties, using either wave). From the recorded wave you can work out the speed of the wave, and using equations you can work out material properties. This is an incredibly important in defining the characteristics of the material within the numerical model. I constructed a finite element model and applied appropriate boundary conditions to represent the foundations of the building, as well as the connections between the section I was investigating and the rest of the Castle. I used the results of the sonic tests mentioned above to determine the masonry material parameters. From the numerical simulations, global frequencies were determined and compared to the results of the ambient vibration testing. global frequency, I mean results that represent the structure as a whole, rather than only a little part of it such as the tower you can see in Figure 4b, or an individual wall. The goal of the finite element model was for its results to be as close to the results of the ambient vibration testing as possible, as this would indicate the model was good at replicating the actual behaviour of the building.

Looking forward, there is a plan to undertake a multi-year project to investigate Durham Castle on a much larger scale, building on the work I have done with the target of investigating the entire Castle. The most intriguing prospect is that when a full finite element model of the entirety of the Castle is built, simulations of different loading conditions can be investigated. This would allow different situations to be modelled and the results determined before any physical changes were done to the Castle.