Berkeley Castle Project Excavation Director Dr Stuart Prior takes a look at one of the many interesting discoveries made during the dig which is part of a new book looking at 15 years of excavation.

Between 2005 and 2019 the Berkeley Castle Project (BCP), conducted by University of Bristol, carried out excavations and survey work at Berkeley Castle, which have led to the publication of a new book. Excavations in 2015, of Trench 19, were able to gain insight into the early origins of the castle and the donjon that was constructed when the castle was built in stone by Robert FitzHarding in 1153–1154.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

It was originally believed that the first stone castle erected at Berkeley comprised a circular shell keep, but the BCP was able to shed new light on this aspect of the site’s past and its architectural evolution. In a Castle Studies Group Bulletin (CSG Bulletin 18, 2014), Neil Guy suggested that the castle may have had a square or rectangular donjon or keep that may have been modified as the basis for the Thorpe Tower by Thomas [III] Berkeley (1292–1361). Trench 19 was designed to look for evidence of the north-west corner and west wall of this postulated donjon. The argument here was that Thorpe Tower was not wholly created ‘as new’ in the 14th century but was instead a part-relic structure arising from a 1340s re-modelling of the 12th century castle. Namely, two corners and one side of a square donjon which abutted the north side of the ‘motte’, and for which the shell-keep encasing the motte was an inner (and elevated or upper) bailey.

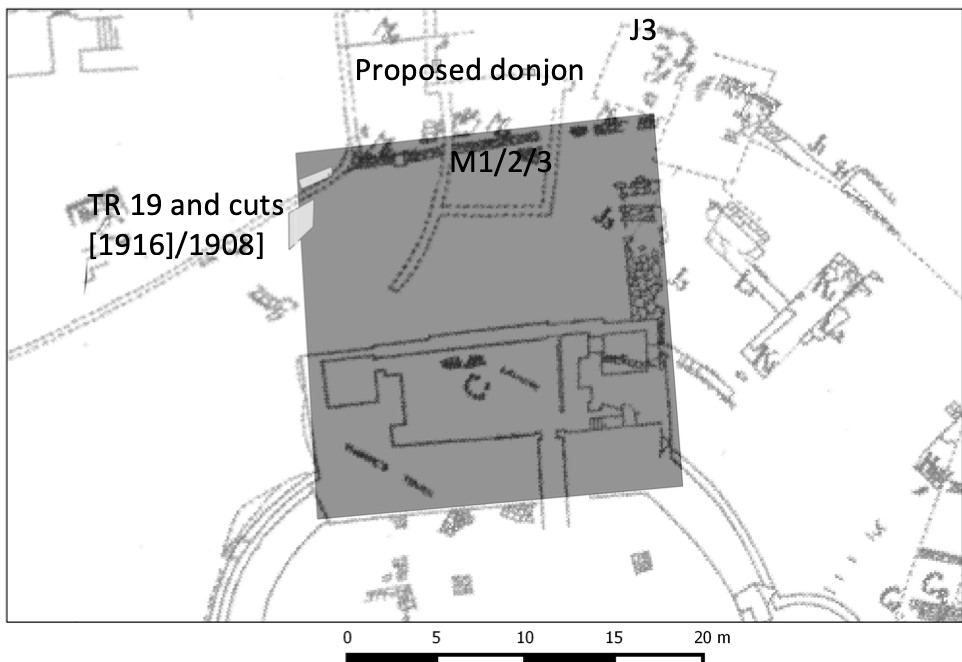

The archaeological remains observed in Trench 19 (Fig. 1) appear to demonstrate the presence of a heavily robbed-out building with structures of two later phases overlying it (Fig. 2). The orientation of the first structural phase (contexts 1912 and 1916) and the robber trench (context 1908) associated with it is in alignment with the south-facing elevation of Thorpe Tower. This orientation suggests that this first phase was associated with, and presumably connected to, Thorpe Tower. It is probable, therefore, that context 1912 represents a heavily robbed wall which is comparable, and most likely contemporary with, wall J3, identified by the 8th Earl, who was an amateur archaeologist, which extended from the northern elevation of Thorpe Tower (TBGAS, 1927, vol.49, 183-93 & 1938, vol.60, 308-39).

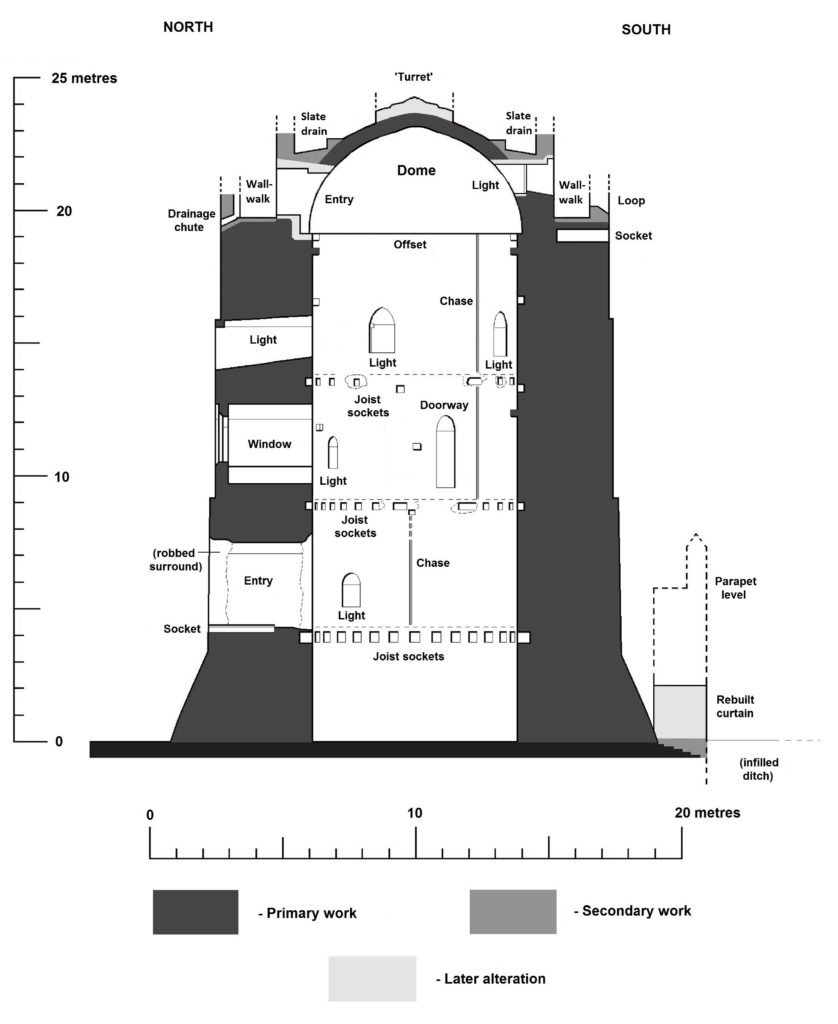

It appears then that the shell-keep and Thorpe Tower are of a single phase, most likely dating to the mid-12th century. While there is no evidence currently that contexts 1912, 1916 and wall J3 are contemporary with this primary construction phase, it must be noted that the wall (1911) overlaid context 1912 and re-used some of its stone. Further to the evidence from Trench 19, the rear wall of this fortification can still be seen, incorporated into the castle’s later form (Figs. 3 & 4).

Accompanying the donjon, there are several medieval documents that record the cutting of moats around Berkeley Castle. In The Cartulary of St Augustine’s Abbey, Bristol, an entry made between 1171 and 1190 records a grant made by Maurice de Berkeley [I] to St Augustine’s of a rent of 5s from his mill below the castle, some tithes of pannage, and common pasture for a plough team ‘pro emendatione culpe mee de fossato quod feci de cimiterio de Berchel circa castellum meum’ (charter no. 78; Walker, 1998, 46–7), which roughly translated means ‘in recompense for my offence committed upon the cemetery of Berkeley in cutting a ditch around my castle’. This suggests that Maurice cut a moat around his castle, which encroached upon part of the cemetery, and he was subsequently fined for his actions. The grant is again confirmed sometime between 1190 and 1220 by Maurice’s son, Robert [II] (charter no. 119; ibid., 69–70).

During this period then, the castle comprised an ovoid shell-keep with adjacent forebuilding, the curtain wall of the inner ward and the Norman Great Hall, all wrapped around the skeleton of the earlier motte and bailey. Excavations carried out by the 8th Earl between 1917 and 1937 (TBGAS 1938, 321) demonstrated that the shell-keep was already adequately defended by a moat that ran around its base on the southwest, north-west and north-east sides – which may have encircled the earlier motte and bailey – and records show that Maurice [I] dug a deep moat around the south-east side of the castle, presumably to complete the defensive circuit, and diverted the Newport brook and others towards the castle to fill it.

More information on the Berkeley Castle Project (BCP), on the castle itself, and on the excavations and survey work conducted by University of Bristol can be found here: https://www.archaeopress.com/Archaeopress/Products/9781803275680

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Bibliography

Earl of Berkeley, 1927. Berkeley Castle. Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society

49, 183-193.

Earl of Berkeley, 1938. Excavations At Berkeley Castle. Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire

Archaeological Society 60, 308-339.

Walker, D. 1998. The Cartulary of St Augustine Abbey, Bristol. Gloucester: Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society.