Dr Edward Impey, one of the UK’s leading castle experts and patron of the CST examines some C13 graffito can boost our understanding of castles.

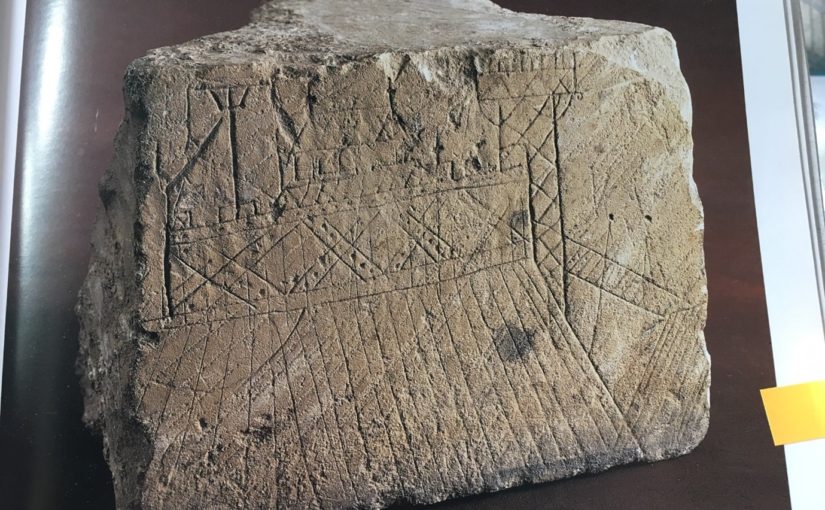

As every castle book reminds us, the defences of most castles before the mid-13th century, and the buildings within them, were built of earth and timber. The perishable nature at least of the timber parts, and their replacement in many cases in stone (obviously) makes their structural detail hard to understand, although Robert Higham and Philip Barker’s Timber Castles of 1992, and their publication of Hen Domen (Montgomery) in 2000 achieve a great deal in this direction. As most evidence is archaeological, however, it tends to be confined to plans and layout. Herein lies the importance of this graffito, scratched into a re-used ashlar in the early 13th century and found during the excavation of the long-demolished donjon in the castle at Caen in 1966: it shows, in elevation, what is unquestionably a timber-framed castle, or part of one – either a ringwork or a motte.

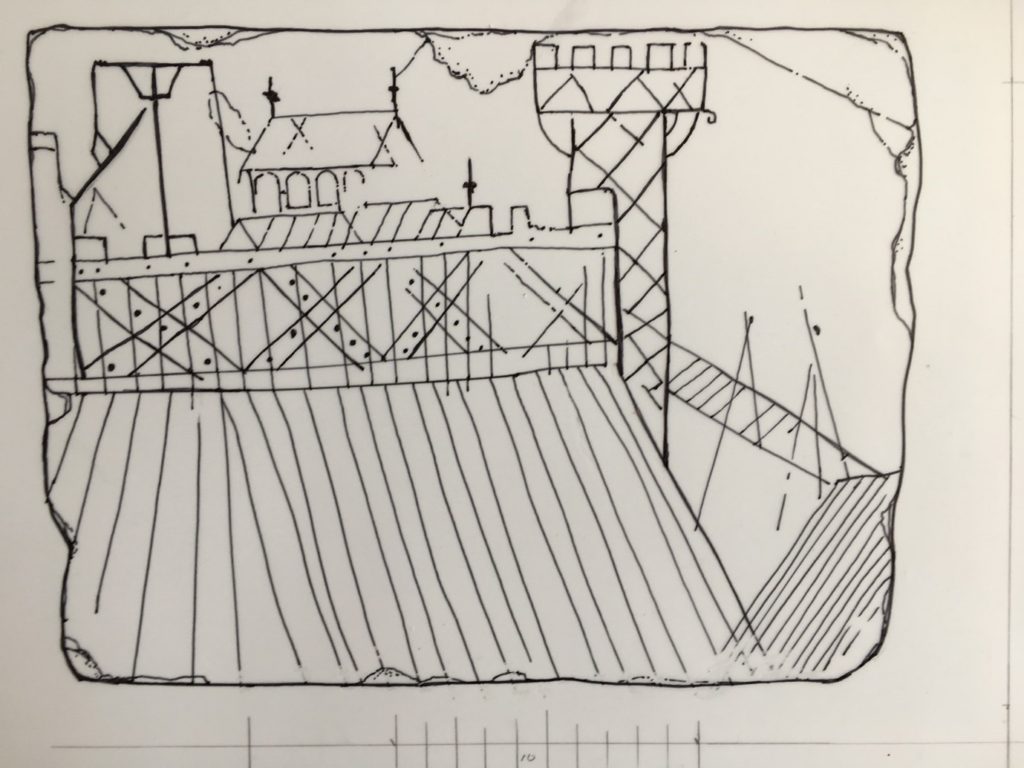

The graffito re-drawn, omitting the underlying mason’s tooling and lines probably unconnected with the original image.

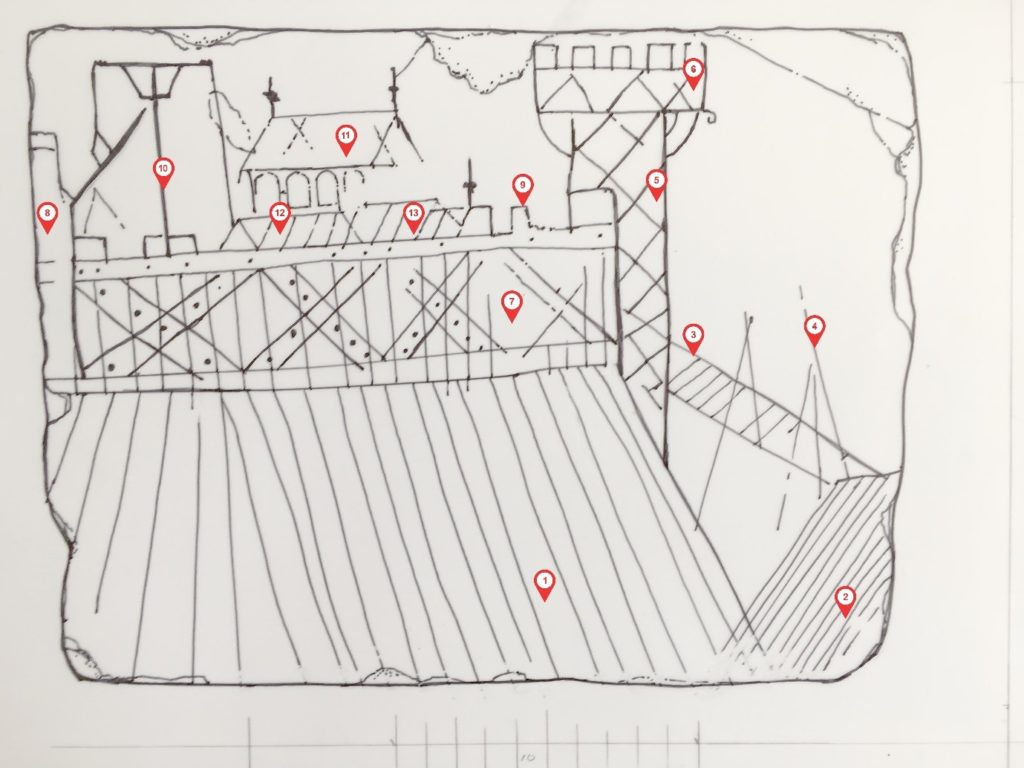

To begin our description with the mound on which the buildings stand, this is marked with a series of lines inclining inwards towards the top, which may be the draughtsman’s device to give it substance, or, possibly, represent baulks of timber covering the slope – a variant of the arrangement found for example at South Mimms (Hertfordshire) and elsewhere. To the extreme right, similarly striated, is what must be the counterscarp of the ditch, and springing from it, possibly propped by two trestle-like structures, is the bridge across it: this is of the so-called ‘flying form’ shown in the Bayeux Tapestry and found archaeologically at Hen Domen. At its top end the bridge abuts a tower, necessarily a gate tower, its side scored with the diagonal intersecting lines, probably representing cross-bracing of the form found in the bell towers at St Leonard’s, Yarpole (1195-6) and St Mary’s, Pembridge, of 1207-23 (both Herefordshire); variants are known in France and over forty post-medieval examples in central Europe. The arrangement is also shown in a carving at Modena cathedral, and in numerous 12th -and 13th– century bestiary illuminations of timber towers on the backs of elephants, prompted either by Pliny the Elder’s or the Books of the Maccabees. Siege towers could be similarly constructed, hence the French term beffroi.

1. Revetted earthwork slope

2.The moat counter-scarp

3.Bridge

4.Possible trestles supporting bridge

5.Gate tower

6.Oversailing platform at tower top

7.Timber wall

8.Possible second tower

9.Battlement

10.Hoist

11.Hall?

12.Second building within the enclosure

Third building

Abutting the tower is the battlemented wall or palisade, composed of edge-to-edge vertical timbers, reinforced by a horizontal rail at top and bottom and by massive diagonal or ‘X’ braces, face-nailed to the uprights.

Inside the enclosure, our draughtsman has shown at least three buildings. The most prominent has a pitched roof terminating in finials, with a row of four round-headed windows under the eaves. Conceivably this was intended as a chapel, but the windows more probably belong to the clerestory of an aisled hall, as survive in the single-aisled hall of c.1160 in the castle at Creully, seventeen kilometres north of Caen, and has been inferred in the 12th-century timber examples at Leicester castle and the Bishop’s Palace at Hereford. In front are two lower buildings with pitched roofs, one carrying a finial.

To the left of the hall is a structure consisting of a vertical pole, a cross-bar at the top, propped by diagonal braces. At first sight rather puzzling, this is clearly identifiable as a crane or hoist, thanks to the dozens of near-identical examples in medieval images, conveniently gathered together by Günther Binding’s compendium of 2001. To the right of the pole hangs a rope, taut as if being pulled or winched downwards, and which is carried over the cross-bar and two faintly-indicated pulley wheels, beyond which it hangs down again and appears to be in the act of hauling a large timber into the air.

The value of the depiction can be summarised as follows. First, it may be the only contemporary representation of a timber-built motte-top or ringwork complex, and is valuable in showing the whole apparatus of palisade, battlements, bridge, gate tower and buildings within. Second, along with the Abbaye aux Dames capital, it is one of only two known representations of face-nailed ‘X’ bracing – an arrangement by definition untraceable archaeologically – which would have endowed the palisade with immense lateral strength and was perhaps widely used. Third, this may be the only contemporary representation of a Romanesque aisled hall – if that is what it is – within a castle. Fourth, as the battlemented platform at the top of the tower oversails its sides, forming a machicolation, it is one a number of images showing that such things did not derive from hourds, but were integral at least to timber towers long before appearing in stone. Fifth, while it has long been assumed that medieval defensive towers in timber were structurally akin to 12th- and 13th-century bell-towers, this is, apart from the Modena carving, the only one to actually show this to be so. Finally, although representing a well-known type, the crane certainly adds liveliness and interest to the composition.

Who the draughtsman was is, obviously, unknown. So is whether the graffito represents a real or imaginary place, although the inclusion of the crane, in use, could be taken as a hint that a particular site, where building works were under way, was indeed intended. What is clear is that it is not a picture of the castle at Caen, nor indeed of Creully, both of quite different form.

Let’s hope that this blog and the forthcoming article (in French) will encourage the identification of other wooden castles scratched in stone, and help with their interpretation and of excavated evidence in the future.

Featured image: The graffito (reproduced by kind permission of the Musée de Normandie, Caen)

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

To find out more about the working being done at Caen you can visit her: https://caen.fr/actualite/un-parc-paysager-la-conquete-du-chateau

Bibliography

M. Baylé, La Trinité de Caen: sa place dans l’histoire de l’Architecture et du plate et du Décor Romans (Paris, 1979),

A.R. Boucher and R.K. Morriss, ‘The Bell Tower of St Mary’s Church, Pembridge, Herefordshire’, Vernacular Architecture, vol. 42, issue 1, pp.23-35

G. Binding, ed., Der Mittelalterliche Baubetrieb in zeitgenössischen Abbildungen, (Darmstadt, 2001), available in translation as Medieval building techniques, (Stroud, 2004).

M. De Boüard, Le Château de Caen (Caen, 1979)

R. Higham and P. Barker, Timber Castles (London,1992)

R.Higham and P.Barker, Hen Domen, Montgomery – A Timber Castle on the English Welsh Border (Exeter, 2000),

Karel Kuča & Jiří Langer, Dřevěné kostely a zvonice v Evropě (Timber Churches and Bell Towers in Europe), 2 vols.(Prague 2009)

N. Molyneux, ‘The detached bell tower, St Leonard’s Parish Church, Yarpole, Herefordshire, Vernacular Architecture, vol. 34 (2003), issue 1, pp.68-72