Lead research on the Weathering Extremes: Medieval Climate Change at Caerlaverock Castle Dr Richard Tipping outlines what he and the team of researchers found during their research.

After an engrossing year of field and laboratory analyses, the team of researchers from the Universities of Stirling, St Andrews and Coventry, along with Morvern French and Stefan Sagrott of Historic Environment Scotland, try to summarise what happened at Caerlaverock Castle, on the Scottish Solway coast, some 600 years ago.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

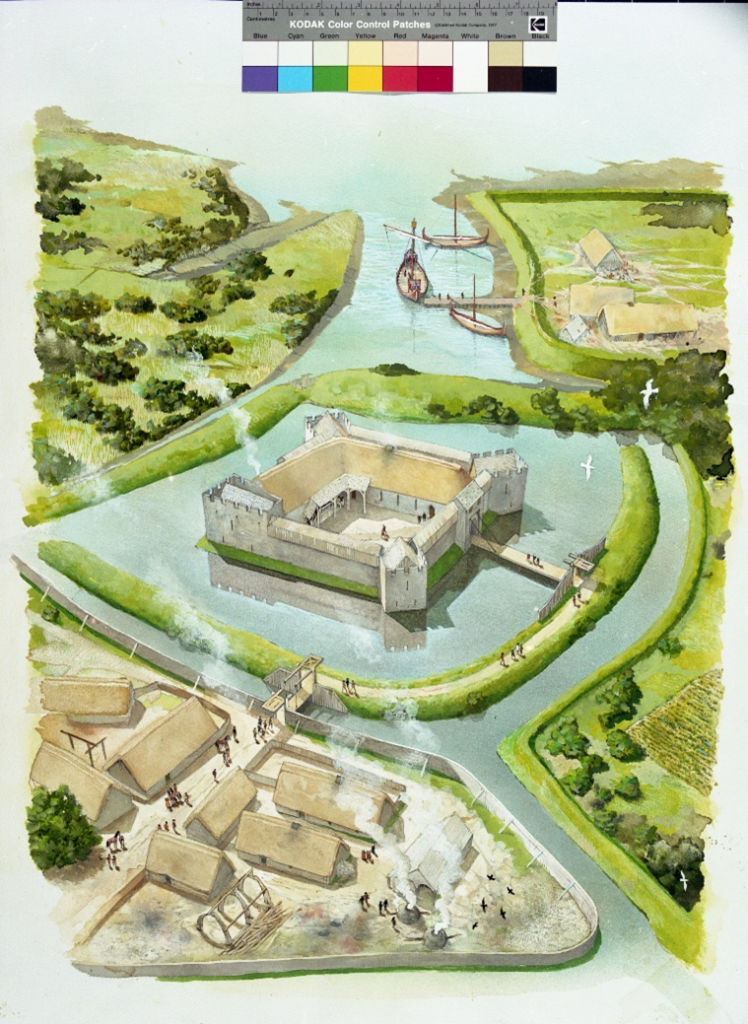

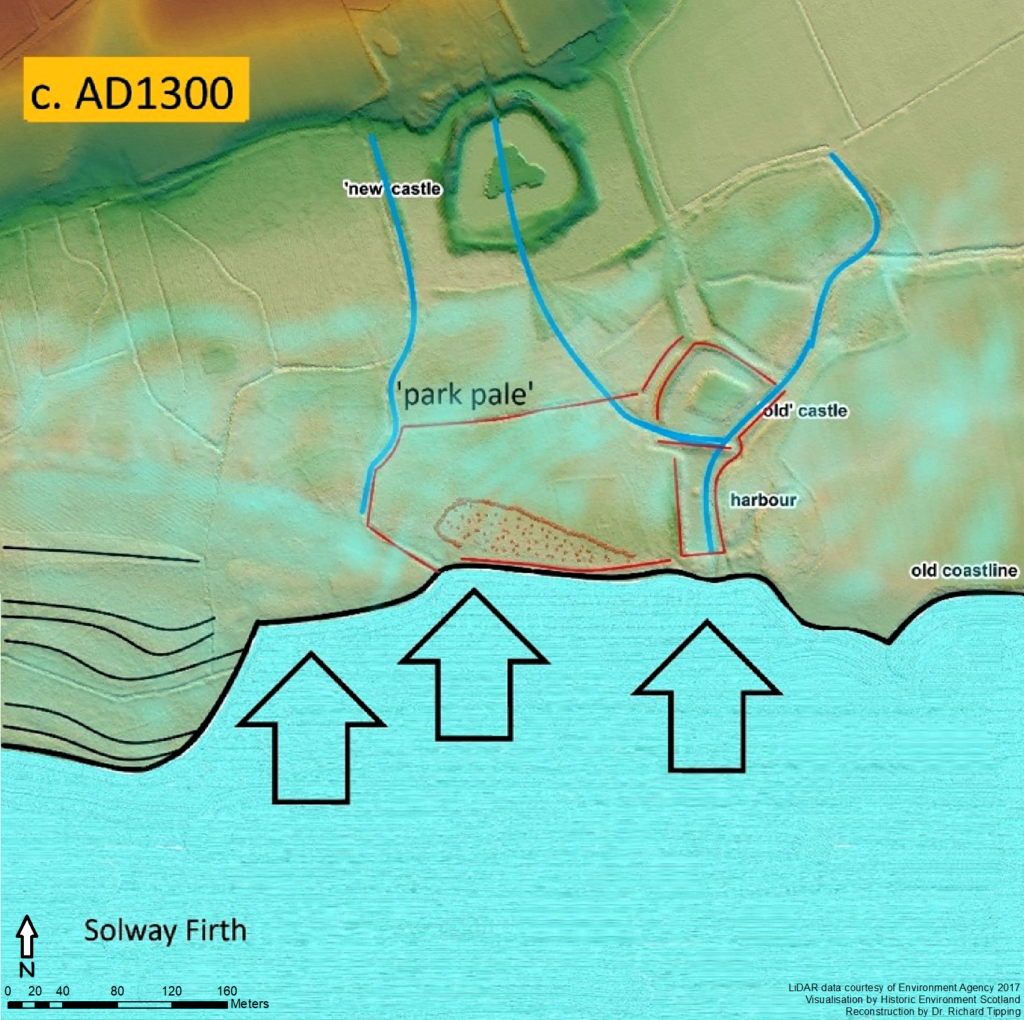

When it was built in AD1229-30, the older of the castles at Caerlaverock stood close to the coast. Salt marshes probably extended south, worked by salt-panners. But the Solway had been far from tranquil. On the coast, preserved intact for around 1,400 years, was a series of huge, 200m long, 20m wide sand and gravel ridges: barrier beaches created by extreme storm surges. They started to form around 200BC, in the late Iron Age, and probably continued into the 1st millennium AD. There were at least four (we don’t know if each was a single storm) that added 200m to the coast.

The builders of the old castle may not have given these much thought. But around AD1200, we think, extreme storm surges recurred, initially with an enormous event that ripped apart the earlier barrier beaches, eroded archaeological structures and impacted the coastal cliffs: we wrote about this event in our third blog . This had minimum wave heights >4.5m above highest ordinary tides. And these waves were not like those surfers play on; these were like tsunami, swelling and not breaking.

We think the builders of the old castle added what has been called a harbour on the coast: our fourth blog described us coring its sediments. These went back 6,000 years, formed when the so-called harbour was a tidal creek, and they probably record the storm surges of the 1st millennium AD. The creek was widened and maybe deepened around AD1200, but even so, waves at the highest ordinary tides could not have flooded the harbour: the harbour wasn’t a harbour. But it was the only way freshwater in the moat system could drain to the sea. It was also, of course, the quickest route for storm surges, increasing in frequency if not scale, to force their way inland. But they didn’t. The sediments in the ‘harbour’ from around AD1200 record still-water, low-energy deposition. We have to think that somehow the ‘harbour’ entrance was blocked off by people increasingly scared of the changing climate – not that they understood what was happening

Our first two blogs described the patient work of understanding sediments trapped in the moat system. Several different types of analysis converge to show that the moat system, inland of the ‘harbour’, was impacted by storm surges, at least twice in the 14th century. How come, when the harbour was blocked? We think the surges skirted round the ‘harbour’, pushing over low cliffs and across parkland to pour into the moat surrounding the old castle. We may not, of course, have recorded the earliest surges, only those after the moat system was dug. We still don’t know whether the storm surges caused the old castle to be abandoned. We think the wave energies were insufficient to undermine the structure. But wave heights will also have rattled the occupants, and we don’t know how big these were: we’ll keep on searching. The salt-panners, by the way, are not recorded after AD1304.

But around AD1277, the old Castle was abandoned and a new one built 200m inland. The final storm surge to impact the long-abandoned old castle was around AD1570, by which time a further six huge barrier beaches had been stacked up. But because its moat had to be filled from the same spring-line that fed the old castle, the new castle could not be located any higher than 7m above contemporary ordinary tides. This, we speculate, created a painful dilemma because this may not have been high enough to escape these medieval and later surges.

This project has demonstrated how our understanding of castles’ construction and landscape can change significantly as new techniques are employed. Also, medieval people were conscious of the effects of extreme natural weather events: a critical topic for the 21st century.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Historic Environment Scotland is grateful for funding received from the Castle Studies Trust, and for research done by Dr Richard Tipping, Dr Eileen Tisdall, Dr Tim Kinnaird, Dr Aayush Srivastava, Dr Jason Jordan, Busie Gisanrin, Neil McDonald, Carla Ferreira, and the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre.

In turn, Richard and Eileen would like to thank Historic Environment Scotland, and particularly Morvern French and Stefan Sagrott, for support and assistance in every aspect of the work, and the Trustees of the Castle Studies Trust for their generous financial support and interest. Stefan Sagrott’s LiDAR imagery of Castle Wood was the catalyst to this work. The Caerlaverock Estate provided access to Castle Wood. Grateful thanks for help with fieldwork go to Valerie Bennett, Finn Thompson, Kath Usher, Richard and Laura Bates, Tim Kinnaird, Aayush Srivastava, Morvern French and Steve Farrar. Lisa Brown (HES) facilitated the 14C dating programme and the re-assessment of archaeomagnetic dating at the old castle. The staff at the SUERC 14C Laboratory, University of Glasgow) are thanked for the provision of 14C assays. Carla Ferreira is thanked for assistance with BACON software. Tim Kinnaird and Aayush Srivastava (University of St Andrews) provided more than just OSL age estimates. Jason Jordan (University of Coventry) supervised the diatom analyses in the western moat undertaken by Busie Gisanrin. Neil McDonald undertook particle size analyses from the western moat and the outer ditch. Steve Farrar (then at HES) and Andrew Burnett enthused over the interpretations.