English Heritage is pleased to be a recipient of a generous grant from the Castle Studies Trust to create a new reconstruction image of Penrith Castle (Cumbria, England). Grant co-awardee Will Wyeth (Properties Historian, English Heritage) discusses this work in the context of the charity’s ambitions for public history.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

The castle of Penrith, made of striking red stone, is arranged in four roughly equal ranges bounding a central off-square courtyard. Of the two towers there survives, the Red Tower retains its north-east wall and, and the White Tower a vaulted ground-floor chamber.

Scholarly consensus ascribes three major phases of construction in the castle: a primary phase of the very late 14th century and two 15th-century phases, the latter of which was the more extensive. It is this last phase, credited to Richard Duke of Gloucester, which is the focus of the reconstruction image.

The castle today is thoroughly urban, and sits within a public park popular with residents and visitors alike. There are several panels offering information about the castle, including an aerial reconstruction of the site in the mid-15th century.

Deconstructing the Reconstruction

The existing reconstruction remains an excellent image. The ranges and towers are carried to full height, the lost courtyard is rebuilt and populated with buildings, while tiny human figures are visible across the site. However, as with many aerial reconstruction images, it has limitations as a device for public history. The image does not aid site orientation for visitors unfamiliar with the ruins or Penrith proper; and life at a human scale is difficult to imagine.

The new reconstruction aimed to address these limitations as well as draw in a further source of guidance. The work of looking after and developing the public history of English Heritage’s properties is supported by a worthy army of volunteers. Penrith Castle is lucky to have one such volunteer, Joanna, who is a true steward of the site’s public history and has led several tours of the castle, gathering feedback on visitors’ responses to it, and the available interpretation. Through Joanna’s experience, we realised we needed a new image, and imagining, of the castle and its everyday inhabitants.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Rebuilding the Castle

It was necessary to start the process of identifying spaces in the castle from scratch. Several 16th-century surveys mention buildings and spaces with attendant measurements, but the detail is misleading. The missing portions of the site fabric today prohibit confidently identifying spaces such as a hall, chamber, kitchen, accommodations, etc. Certain architectural features survive which can help, but a convincing and comprehensive reconstruction was not achievable.

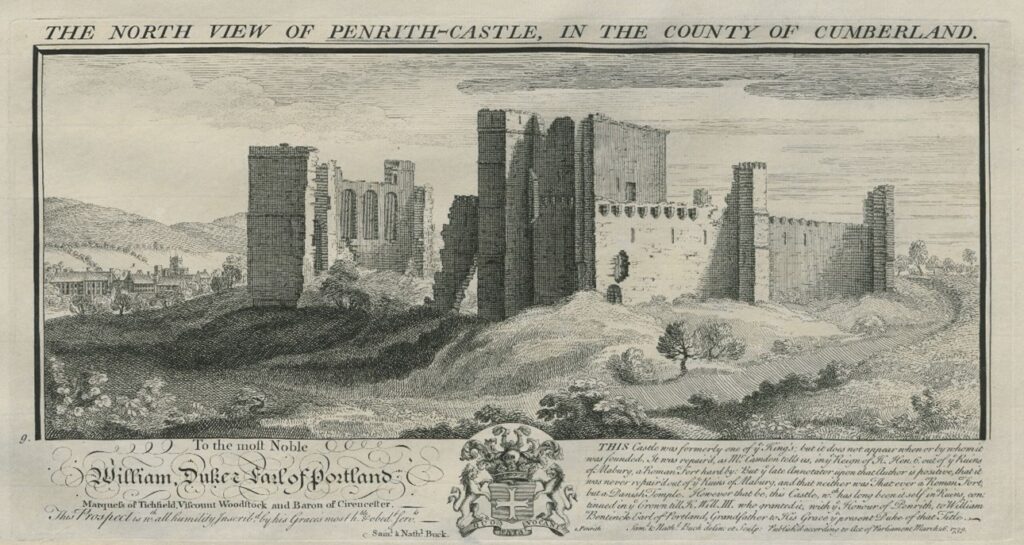

Some early images help to locate specific buildings. The Buck image of the castle (1739) illustrates the castle in a more complete state than today – including a complete section of walling where only the reveals and partial window-head of the ‘hall’ survives today – but it also testifies to the presence of a lost tall block positioned on the castle’s west corner (Figure 4).

The great hall was identified by the tall windows in Bucks’ image. This is an unorthodox position. It was unusual for a great hall to be positioned so close to the formal entrance to the castle (in the hall’s primary phase, positioned at the east end of the south range; in Gloucester’s time, just west of the hall). The kitchens which serviced it were also on the other side of the enclosure.

Other ideas were mooted. The presence of a chapel identified with some confidence at the upper level of the east corner of the castle precluded identification with this space in that capacity (see Figure 1). It is possible the three-windowed space was a private or state chamber. While feasible, this pushes the necessity of a great hall elsewhere in the castle where there is not space for it. The high wall outer wall of the surviving south-east range has few outer windows of any significance; the south-west range was, it would seem, dominated by the large tower depicted in the Bucks’ image and resting upon masonry identified with Gloucester’s work; while the north-west range in Gloucester’s time had a number of fireplaces at ground floor whose flues would rise through a first-floor hall set above them, making this alternative, hypothetical arrangement unlikely. For want of alternatives the present consensus, that that hall was in the positioned identified by the Bucks’ three-window wall, is probably correct.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

The New Reconstruction

The new image was developed in collaboration with artist Pete Urmston from an existing photograph (Figure 4, left). This captured several parts of the site which we wanted to reconstruct – the great hall with access stairs, Red Tower and parts of the Gloucester-era gatehouse. It incorporates the part of the castle most familiar to passers-by – the Red Tower – and an assemblage of standing features which in general visitors find difficult to understand. This perspective also granted greater flexibility to create scenes of human interaction in the foreground of the image which might populate the castle and convey a sense of Penrith’s medieval community.

The process of reconstruction begins with a line sketch superimposed upon the base photograph (Figure 4), and hereafter a sequence of amendments and insertions ultimately leads to the final image (Figure 5). The cutaway into the great hall, and beyond into the Red Tower, gives some sense of the grandeur and scale of lost interiors. The clerestory in the hall, inferred from antiquarian sketches and some degree of analogy with that at Middleham Castle, is defined by windows set on a wall carried by a projecting corbel table. A two-door timber screen of late 15th-century design covers off the lower part of the hall. The window-heads of the gatehouse first-floor echo surviving dressed stone fragments found at Penrith.

Perhaps most significantly, the castle is populated with a scene from its tenure by Richard of Gloucester – a meeting of castle staff with tenants and poor folk to hear pleas. A single figure who is attested at the castle and whose presence would be in keeping with a day-to-day scene in castle life in the late 15th-century is represented: Sir Christopher Moresby, depicted on the far left standing with a staff and wearing a green coat (Figure 6).

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Moresby supervises under-stewards seated on stools and by a trestle table. Just in front of the restored stair block where a figure descends, painted in Gloucester’s colours of white and blue, are two boys sweeping the yard (Figure 7). Their attention has been captured by a black and white cat standing on top of some barrels. Behind them, through the cutaway, are two figures in the hall basement. One is just entering while the other is sampling (perhaps illicitly) the stores of ale.

In the hall at first floor are three parallel scenes: well-dressed figures are assembled on a long bench and trestle table in the hall proper. A woman enters the screened area at the low end of the hall from the buttery in the first floor of the Red Tower, visible through the inner cutaway. Leaning upon the sole standing piece of wall that survives in this space today, two servants are bringing down a blue hanging.

The new reconstruction aims to place the people of Penrith Castle at the centre of its re-imagination, while bringing back its lost buildings and interiors. In time the image will feature on a new panel scheme in the castle. In the immediate short-term, Joanna the volunteer is already armed with the image and sharing the new light it brings to the castle with visitors.