The Barons’ War and Lady Nicolaa de la Haye

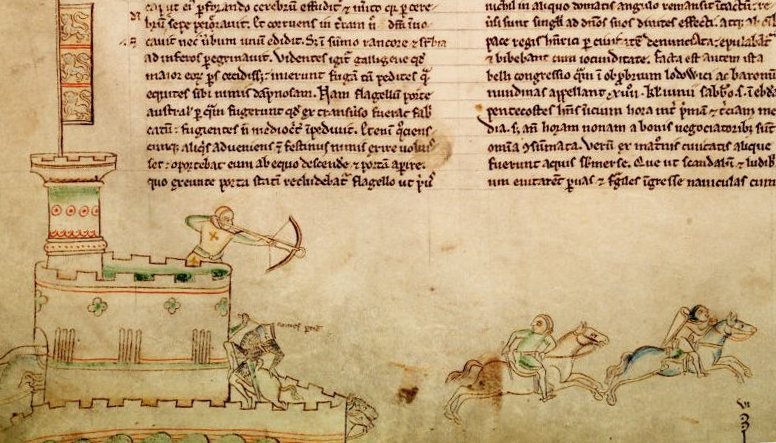

King John’s reign is notorious for his disagreements with his barons, leading to the signing of Magna Carta, civil war, and an attempt to Prince Louis of France on the throne. In 1215 Nicolaa de la Haye became castellan of Lincoln Castle, a title previously held by her father. She held the castle for John, and established a truce with one of the rebellious barons when they invaded the town of Lincoln.

King John visited Lincoln in 1216 and Nicolaa asked the king to be relieved of guardianship of the castle, saying that she was too old and wanted to be unburdened by the duty. John valued her staunch support, and declined her request. In fact, on 18 October he made Nicolaa sheriff of Lincolnshire – it was very unusual for a women to have such a position of direct power at the time, and shows how important Nicolaa was to the king’s efforts.

Though John died on 19 October 1216, the war continued with his supporters fighting for his son, the young King Henry III, while the rebellious barons continued to back the French prince. The war came to a head at the battle of Lincoln on 20 May 1217, resulting in a royalist victory which turned the tide in favour of Henry III. Nicolaa was instrumental in defending Lincoln Castle, but was removed as sheriff just a few days later.

Alice Knyvet stands up to the king

Buckenham Castle lays close to the village of New Buckenham in Norfolk. The circular keep, remains of which are the only surviving building works of the castle, is the earliest known in England dating to c. 1145-50. The castle was demolished in the 1640s by Sir Philip Knyvet, perhaps as a request from Parliament.

Contained in the Patent Rolls of King Edward IV’s reign is a story detailing the defence of Bokenham Castle by Alice Knyvet. In 1461, Edward IV claimed Bokenham Castle by virtue of legal inquisition. The castle was, at the time, owned and occupied by John and Alice Knyvet, who did not easily relinquish their estate. The king sent nine commissioners and an escheator to take the castle, possibly knowing that John was away and the castle would be easily handed over.

However, as they approach the outer ward, Alice appeared in the gatehouse tower with the drawbridge raised who kept the castle ‘with slings, parveises, fagots, timber, and other armaments of war’ (CPR, 1461-7, p. 67). We are told that Alice along with William Toby of Old Bokenham, gentleman, and fifty other persons were ‘armed with swords, glaives, bows and arrows’. Alice addressed the commissioners thus:

Maister Twyer ye be a Justice of the Peace. I require you to keep the peace, for I will not leave possession of this castle to die therefor and if ye being to break the peace or make any war to get the place of me, I shall defend me, for liever I had in such wise to die than to be slain when my husband cometh home, for he charged me to keep it (CPR, 1461-7, p. 67).

The narrative described in the Patent Rolls is telling for a number of reasons. Fistly, Alice does not appear to hesitate when royal officials approached her castle demanding that they legally had the right to seize it. Secondly, the fact that the royal commission waited until Alice husband, John, left speaks to their utter miscalculation of her authority and ability to militarily command the battlements. Ultimately, no actual physical fight took place, but Alice’s strategic placement of armed people on the towers meant the castle, at least, appeared to be well defended.

Queen Mary takes control

Though little remains of Roxburgh, in the Middle Ages it was one of the most important castles in Scotland. King David I ruled Scotland from here and it changed hands several times during the wars between England and Scotland. In 1460 King James II besieged the English-held Roxburgh in an attempt to capture the castle. He died when a cannon he was stood next to exploded. The gun might have been fired to mark Queen Mary’s arrival.

Mary took charge of the siege and summoned her young son to be present when the castle fell. The Scots captured the castle they chose to demolish it. James II’s prize had come at too high a price. The 9-year-old James III was too young to rule on his own so Mary was the power behind the throne for the next few years until her death in 1463.

Lady Anne Clifford and Brougham, Brough, and Appleby

By the time the English Civil War broke out in 1641, many castles were neglected or downright ruinous. While some were pressed into action during the conflict, many suffered further damage from siege or slighting.

Lady Anne Clifford had spent years trying to secure her inheritance which included a number of castles. In Westmorland, her castles at Appleby and Brougham had been besieged and damaged during the war, as was the case with Skipton in Yorkshire. From 1650 Anne used her considerable well to repair and restore these castles, as well as Brough which was gutted by fire in 1521. She established Brougham Castle as her main residence and created a garden on the site of the adjacent Roman fort. It is likely that without Anne’s intervention these historic sites would have slipped further into decay and may have become lost to us.