The final results are in and Dr Andrew Blackler, project lead for the Dating of the Towers of Chalkida, Greece, reveals the surprising findings of the project we funded in 2022 to try and date the hundreds of towers in the region.

In the autumn of 1204 forces of the Fourth Crusade, fresh from their capture of Constantinople, annexed central Greece. Studies have been undertaken of the major fortifications they constructed, but little is known about the hundreds of towers, which are today a ubiquitous reminder to the modern tourist of the medieval period in the region.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

The traditional interpretation is that they were built by the incoming westerners- the minor nobility – as part of a process of colonisation, to display and impose their power over the local Greek population. Yet, since no scientific study has ever been undertaken, we could not even be sure when they were built, and therefore why they were constructed or by whom – until now.

and the towers sampled (inset)

Following a two-year research program, funded by the Castle Studies Trust and led by Andrew Blackler, a member of the five-year ‘Hinterland of Medieval Chalkida’ survey, surviving towers in central Greece have now been dated using modern laboratory techniques. In October 2022 a team, including technical staff from the Institute of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology ‘Demokritos’ in Athens and from the Ephorate of Antiquities in Chalkida, took samples of wood and mortar from seven surviving towers on the island of Evia (Euboea). This is the second largest in Greece and runs two hundred kilometres down its eastern seaboard. The island, just seventy kilometres north of Athens, is separated from the mainland by a narrow strait only thirty-nine metres wide, the tidal flows of which even Aristotle failed to solve! Chalkida, its capital, became the Venetian administrative centre (as Negroponte) of its Aegean possessions in 1390 and, following its capture by the Ottomans in 1470, their capital of Central Greece for 350 years until the formation of the modern Greek state.

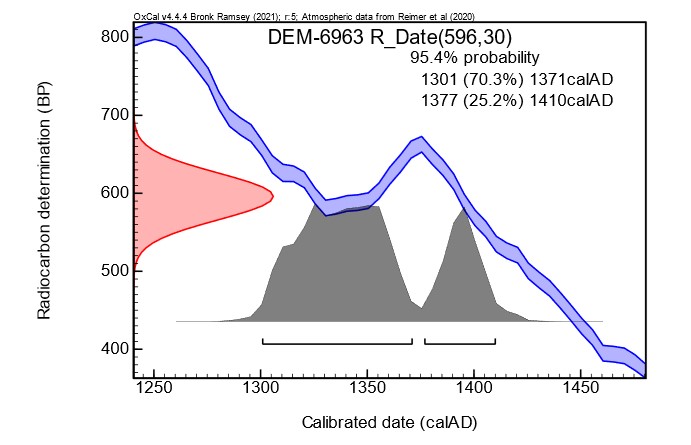

All of the towers (walls about 8 x 8 metres and height up to 18 metres) were in an advanced stage of collapse. Samples were taken of the wood inserted to provide internal lateral structural integrity to their walls, and of the mortar used to bind their rough stonework. This ensured that these materials were not part of a more recent repair or renovation, which would have been the case for beams used to support the multiple floors of the towers, but part of the original construction phase. The ten timber samples obtained were then subjected to a process of radiocarbon (14C) dating, whilst the mortar was analysed using optical and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and other techniques (pXRF and XRD) at the Demokritos laboratory.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

The results have been exceptional. Six towers from different topographic locations (coastal, floodplain, mountain areas) have been dated with 95% certainty to a period between 1270 and 1434. Unfortunately, the accuracy for most samples was only approximately +/- fifty years due to fluctuations in the cosmic concentration of 14C in the earth’s atmosphere caused by solar activity during the fourteenth century: there were therefore two possible dating ranges identified. Two samples were of sufficient quality that, using what is known as ‘wiggle’ analysis, more accurate dating was obtained.

The analysis of the mortar samples also demonstrated that two towers had two phases of construction. It is difficult to know whether this was a deliberate action or simply a reconstruction due to the collapse of the upper levels, given that the region is subject to frequent seismic activity. More importantly, since we could not identify any timber samples for one tower, it was possible to show that the chemical composition of this tower’s mortar was similar to two other towers in its immediate vicinity and thus was possibly also constructed in the fourteenth century.

The general conclusion, therefore, is that all the towers studied were probably built at least a century, or five generations, after the annexation of the region by western forces, and no towers were built immediately after the Crusaders took control. The ’colonial’ interpretation of their role is thus overturned or, at the least, requires reconsideration. Rather, their construction appears to have been a reaction by landowners to increasing instability in the region following invasion of the island by Byzantine forces in the 1270’s, the threat of attack by the mercenary Catalan Company who took control of Thebes and Athens in 1311, and a growing fear of seaborne assault by Turkish corsairs in the fourteenth century.