An enigmatic ruin

County Roscommon’s Ballintober Castle was probably built by Richard de Burgh, Earl of Ulster, in the early 14th century. It changed hands several times, but from 1381 it was under the control of the O’Conor family. After nearly being attacked in 1642, the castle was abandoned as a residence and the elements have left Ballintober as a ruin. The O’Conor family still own the castle today.

Despite Ballintober’s storied past and impressive ivy-clad remains, archaeologists first investigated the castle in 2008. When Niall Brady applied to the Castle Studies Trust for funding in 2013 the project to survey the castle offered the chance to push forward our understanding of the castle.

Though the castle now lies in ruins, parts of it stand up to 4m high (13ft). Ballintober Castle is rectangular, measuring 73.8m by 80.5m (242ft by 264ft). There is a tower at each corner, and on the east side the entrance is flanked by two further towers. The polygonal corner towers are thought to emulate the design of Edward I’s Caernarfon Castle in Wales. As well as being a military structure, emulating the most powerful of royal castles, Ballintober was a residence. Its comfortable accommodation revealed by the fireplaces marked it as a palace castle.

Ballintober is a ‘keepless castle’ which means it does not have a great tower such as the one seen at Trim Castle (Ireland) or Dover Castle (England). Instead it relied on its outer walls. There are a few castles like Ballintober. Richard de Burgh also built Ballymote as a keepless castles around the same time. Just 18km (11mi) to the south-east is Roscommon, which may have provided the template for Ballintober. It was built decades earlier in 1269 on behalf of Henry III. Ballintober is the largest keepless castle in Ireland, and is more than twice the size of Roscommon despite its royal patronage.

Surveying the ruins

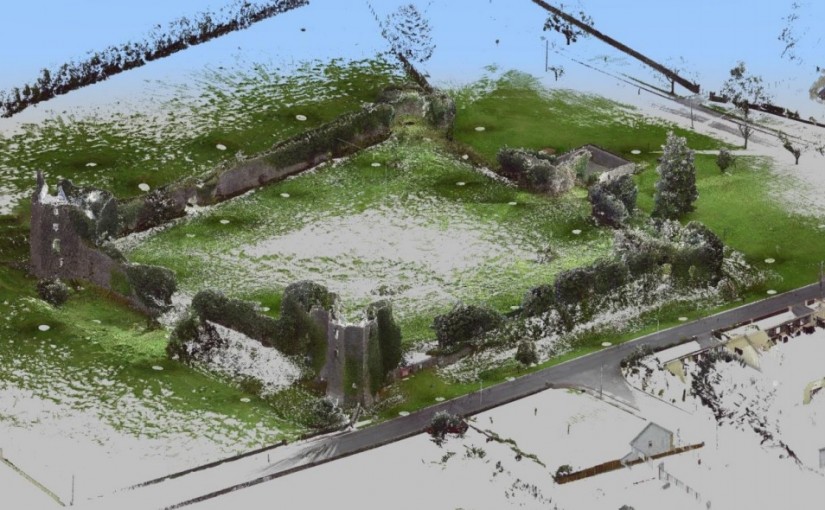

Laser-scanners were used to record the standing structure and as a result we have a 3D point cloud which can be used to create accurate plans, elevations, and views. The survey took three days to complete in the field, followed by considerable time processing and interpreting.

It’s told us a lot about the castle. The south-west tower has a fireplace on the ground floor, and would have once had a fine timber vault. It may have housed a high-status hall. While it’s possible the south-east tower is the oldest as it is the smallest of the corner towers, the north-west tower was substantially redesigned in the 17th century. The arrow slits are wider than those found at Roscommon and Ballymote, and may be wider. This might suggest that comfort was a consideration in their design. There are signs of later adaptation, with gun loops being added to accommodate gunpowder weapons.

The survey also shows that Ballintober Castle is asymmetrical, with the entrance off centre. One possible reason is that the design changed to encompass a larger area or perhaps it stands on an earlier fortification.

An eye to the future

Importantly, the survey paves the way for future work: from July to August this year Foothill College, California, ran a Summer Fieldschool at the Castle. ‘Castles in Communities’ is advertised on the Archaeological Institute of America website. Niall Brady was one of the fieldschool directors. We asked him how the excavations went:

“The CST-funded survey in 2014 was a very important precursor to starting the present work. The 2015 season went well. We focussed on questions associated with tracing missing lengths of the standing walls, rather than looking into the main interior. This was to give us some sense of the site’s stratigraphy, while also tackling obvious questions in a way that wouldn’t open a can of worms we couldn’t close. We also engaged the attention of a conservation engineer, who is now quite excited by what can be possible in future years, vis a vis conservation works on the standing remains.

“For the four weeks on site, the excavation results were good, showing 16th-century and later levels. We only really broke the ground surface in three discrete locations, and so look forward to going deeper and exposing medieval horizons next year. There was massive buy-in from the local community (the landowners and the villagers), who see the great potential that lies in our plans for the castle site and its living community about it.”

The work the Castle Studies Trust is not the end point of a journey, but a crucial stepping stone towards understanding medieval society.

For more information on Ballintober, read the full length report prepared by Niall Brady. Please donate so we can support more projects like the one at Ballintober.