Aerial photo of Pembroke Castle from the west, showing parchmarks (Crown Copyright RCAHMW, AP_2013_5162)

New work by Neil Ludlow and Dyfed Archaeological Trust (DAT) has revealed the remains of long-vanished buildings, and other features, at Pembroke Castle. Pembroke is famous for its large round keep, built by earl William Marshal, and a number of stone domestic buildings are preserved in the inner ward. But the large, outer ward has been an empty space since at least the eighteenth century.

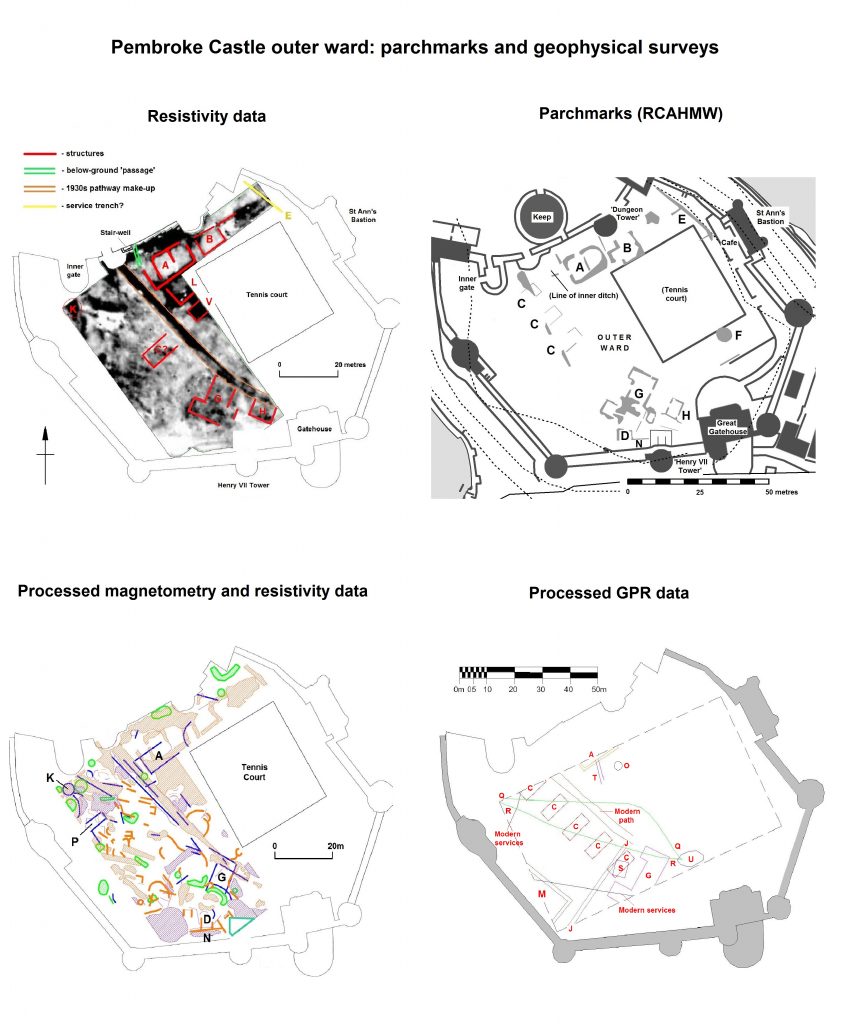

In 2013, routine aerial photography, by Toby Driver of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales (RCAHMW), revealed a number of ‘parchmarks’ in which the outlines of buried walls could be seen, as shorter grass, in the castle. He contacted Neil, who applied to the Castle Studies Trust for a grant to carry out further work at the castle. Thanks to their funding Neil, in partnership with DAT, was able to undertake a full geophysical survey of both the inner and outer wards in May 2016.

Three different methods were applied. Magnetometry, which measures magnetic variation below the ground, was carried out by DAT while Tim Southern undertook resistivity survey, which measures electrical resistance, on DAT’s behalf. Both processes can reveal buried walls and ditches and Ground Penetrating Radar, which can detect features to a depth of over 1.5 metres, was also undertaken in the outer ward, by Tim Fletcher of TF Industries Ltd..

Survey in the inner ward suggested that two or possibly three previously unknown buildings may lie beneath the grass, but they couldn’t be dated or characterised. At least one of them may, however, be connected with food preparation as neither a kitchen nor bakehouse has yet been conclusively identified at the castle, which would have been necessary to feed the people who made up the earl’s household, his retinue, and the garrison.

The results in the outer ward were outstanding – and surprising. Even allowing for later disturbance, which was slight, the area seems to have been largely empty of buildings during most of the Middle Ages – in contrast to the busy, congested scene that’s normally imagined. This area was enclosed with an impressive curtain wall and towers in the mid-thirteenth century but may always have been envisaged as an open space – for ‘civil’ assembly, for military gatherings, for pageantry and display or for leisure, or perhaps all four; a garden was certainly present by the fifteenth century, and may have been laid out around 1300-20.

Some buildings were however present. A large rectangular building M against the southwest curtain wall, and a possible smaller lean-to N against the southern curtain, are both probably medieval; was the large building for storage, or was it domestic? To account for the apparent absence of a well in the castle, a number of local stories had developed including one which involved a system of water-pipes; the discovery of a possible well, O, may solve the mystery. Most exciting of all was the confirmation that an arrangement of parchmarks G, recorded in 2013, belong to a free-standing, winged mansion-house. Its form suggests that it’s from the late fifteenth century, and it may have been the building within which King Henry VII was born, which is known to have stood in the outer ward.

A ditch formerly separated the outer ward from the inner ward, and a buried masonry structure K, opposite the inner gate, may be a bridge abutment. This ditch was possibly infilled to improve the setting of the fifteenth-century mansion, and garden. Alternatively, the infill may belong to the Civil War period (1642-48) when the castle was held against the Crown, and then against Cromwell. Two former buildings A and B, which overlay the infilled ditch, may date to the Civil War; one of them was associated with a below-ground ‘passage’ that may be a gunpowder magazine. The castle again saw military use during the Second World War, when five ‘Hall-huts’ C were built to house troops based at the castle.

While a number of the other features denote modern service trenches, some may belong to early use of the castle site. A linear feature J may represent the boundary of a burgage plot, perhaps confirming that the outer ward was laid out over part of the town; if so, some of the patchwork of smaller, formless features may also be urban in origin. Others may be hints of prehistoric occupation.

While the results show what can be achieved through geophysics – and generous grant-aid – more work is required before they can be fully understood. In particular, even limited excavation in the mansion may confirm its date and form, and suggest how the outer ward was used during the fifteenth century. The mansion seems to have contained a latrine, so with luck some good palaeoenvironmental evidence has been preserved. Pembroke is a castle of national significance, both architecturally and as a setting for major historic events: it will repay close study.

One thought on “Geophysical survey at Pembroke Castle”