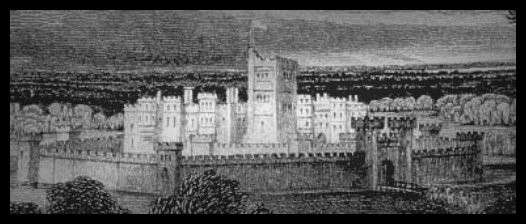

I’d heard of Lathom House, but the familiar reconstruction of this principal monument of Tudor England is a Victorian engraving that may bear little relation to historical fact. Those engravers never saw it, as it had long gone by then. No drawings survive, but enigmatic descriptions of nine (or was it eighteen?) towers, the space they occupied now thin air and branches.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Lathom House is in a garden – or rather, here lay its site. This garth is isolated, bounded by a sandstone wall and a ditch in a flat Lancashire landscape that in winter stretches the concept of fallow into a deeper somnolence. In summer its shrubs and trees burst into colour and scent, and you may be caught off-guard by the cry of its peacock strutting in the remnants of a nineteenth-century planting scheme. There is no sign at all of the medieval house, but for the occasional scrape of a trowel blade on revealed cobbles and footings.

Fifty yards from this lost garden is the rump of the last Lathom House, built in the 1720s to the designs of Giacomo Leoni. After two centuries, this Palladian mansion was demolished in 1925–9. It had provided a replacement for a house that was also ravaged – but not totally destroyed – during the civil war, and whose central ‘Eagle Tower’ was the principal monument of the Stanley family, kingmakers at Bosworth Field in 1485. After the battle brought Henry VII (1485–1509) to the throne they built to the scale expected for a residence of Margaret Beaufort as the Lancastrian king’s mother, and Thomas Stanley, the last King of Mann who presided over Lancashire and Cheshire with a view across the Irish Sea. Lathom was so grand it was termed ‘The Northern Court’ in 1572, with the claim Henry VII, who visited in 1495, had based Richmond Palace on its turreted skyline. It has recently been demonstrated that the king left his marriage bed here, having executed William Stanley his Lord Chamberlain on charges of plotting. It inspired the basis of a school of joinery centered on Lathom. Much of this furniture survived the civil war, as heavy beds were propped against the great gates against cannon fire, whereupon the chattels escaped with the family.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

The comparison of Lathom and Richmond is hard to substantiate, and so completely lost was this grand house that its location has been hotly disputed. In the last twenty years, the occasional archaeological investigations in the garden and at the dilapidated remains of the Georgian house have revealed a wide array of footings and salvaged cut stones. The Lathom Park Trust and latterly the Kingmaker 1485 project led by Steve Baldwin with Dr Rob Philpott, Dr Clea Paine and George Luke have championed a deeper understanding of the site and brought public access and involvement in archaeological discovery, training and recording.

The involvement of diverse groups at separate digs has resulted in the need for a collation and analysis of discoveries, which have not hitherto been catalogued in one place nor attributed with an original context. The Castle Studies Trust funded a project to analyse the scattered masonry and identify it as far as possible through comparative evidence. After several months of looking, measuring, thinking, discussing and researching, the results have set the diverse stones within a timescale stretching from the fifteenth century – some perhaps earlier – to the Jacobean age, exactly as expected if they were the remains of Lathom House.

The most diagnostic features include chimney caps, early seventeenth-century window mullions and sills, carved stones with oak leaves compatible with the Stanley arms, and the tantalising possibility of a medieval memorial slab. These offer a clear picture of the waves of construction, which peak at the era of Bosworth, and the turn of the seventeenth century. The latter may tally with another royal visit, that of James I in 1617.

I write this ahead of giving a talk on the findings to the local community. The biggest realisation is that Lathom’s Eagle Tower was almost certainly based on the polygonal Eagle Tower at Caernarfon – Edward I’s fortress – for which the Stanleys became responsible in the 1480s just at the time they rebuilt Lathom to represent their role as kingmakers. The internal area of this building and the number of stories tally closely with Caernarfon, allowing us to begin to reconstruct lost Lathom and – as importantly – appreciate its significance in the minds of those who knew it.

We don’t yet have the full picture, but understanding the masonry undoubtedly establishes the building blocks for the years of archaeology that lie ahead.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Jonathan Foyle will be speaking about his work at Lathom on Wednesday 25th October.