The excitement of Halloween has quickly set upon us at the Castle Studies Trust, and we thought we would explore the connection between witchcraft and castles. Castles have a long history as the walls that confined accused witches; the prisons that kept their magic at bay.

Grab your brooms and cauldrons, we are headed to Leeds Castle in Kent. Leeds Castle was famously purchased by Queen Eleanor of Castile, wife of King Edward I, in 1278. The queen enhanced its defences and possibly commissioned the lake that surrounds the residence. In 1321, the castle saw military action when it was captured by the forces of Edward II from Margaret de Clare, Baroness Badlesmere. The winter of 1381 witnessed Anne of Bohemia, Richard II’s first wife, stay at the castle on her way to her wedding. The castle, thus, had a long history of the seat of female agency and power. It was not until the fifteenth century that the castle was used to enclose and suppress queenly authority.

Joan of Navarre, Queen of England and wife of Henry IV is the only queen of England to be imprisoned for witchcraft. In the autumn of 1419, the duke of Bedford and Henry V’s council reported a case of suspected witchcraft in the highest possible circles. Queen Joan was accused ‘of compassing the death and destruction of our lord the king in the most treasonable and horrible manner that could be devised’.[1] The queen along with her confessor, John Randolf, a friar of Shrewsbury, had according to contemporary chroniclers dabbled in sorcery and necromancy. The royal court and much of the public opinion quickly became ‘feverish with rumours of witchcraft’.[2] Queen Joan was imprisoned for nearly three years, and all her servants and property were taken from her. She was first imprisoned in Pevensey Castle in Sussex and in the last two years of her house arrest she appears to have been kept at Leeds Castle.

Although imprisoned in the castle, Queen Joan’s surviving household accounts detail the purchase of luxury items, including minever and other furs, tartarin, silk laces, ords, and thread, sindon and Flanders linen.[3] The cash flow in the household accounts has led Alec Myers to conclude that these surely shows that the king did not believe that she had been practicing witchcraft in a treasonous way. The move to accuse and imprison Queen Joan had its obvious political and financial advantages for the king. Indeed, with the accusations of witchcraft the king was able seize all her possessions and revenues. Nevertheless, Queen Joan paid the price of her freedom for the accusation, whether it was false or not. The crime of witchcraft was used – in this particular instance – for the political manoeuvring of powerful men and the castle walls were meant to ensure the enclosure of a powerful woman.

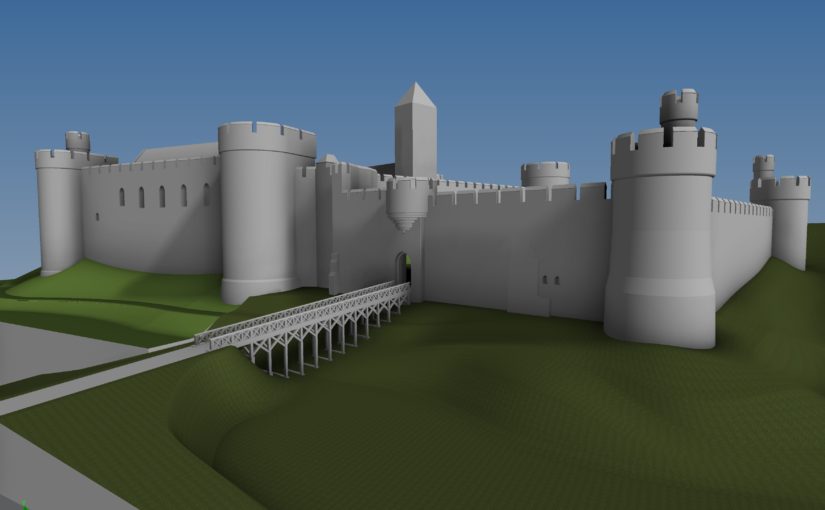

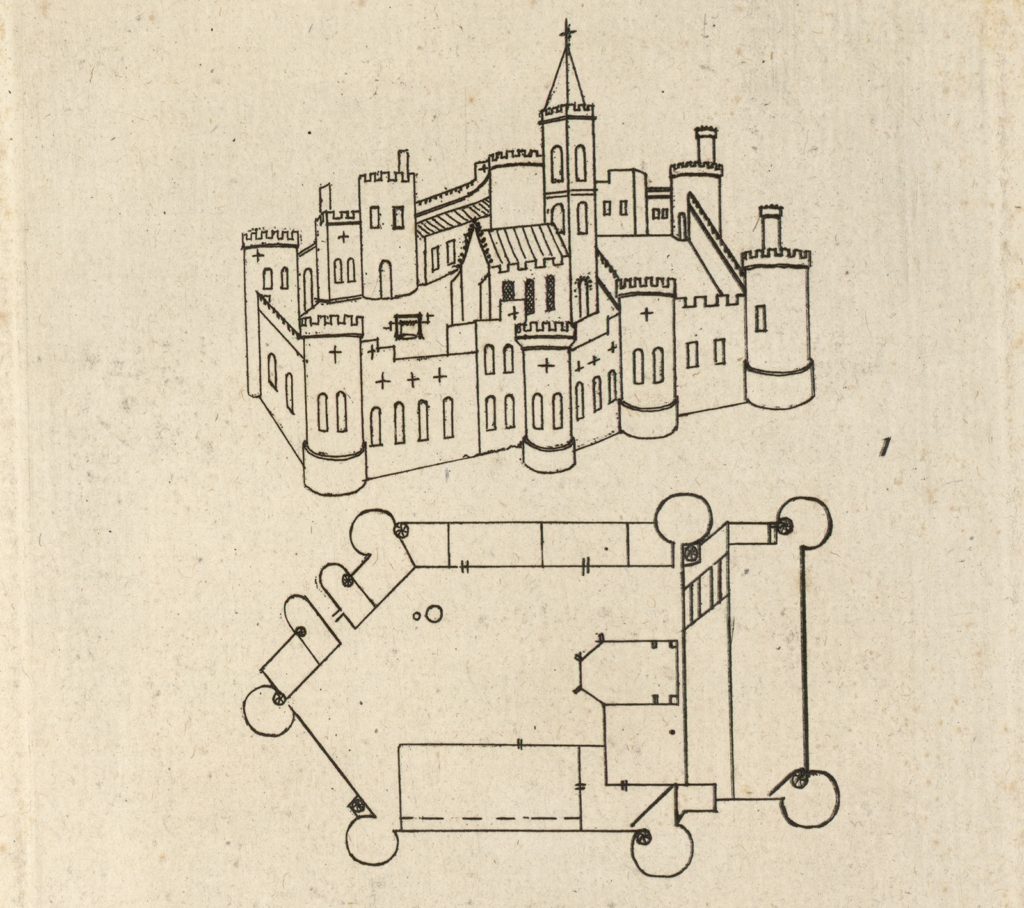

From Leeds Castle, we move to Lancaster Castle; a castle with medieval origins was used as a prison starting in at least the Tudor period. Nearly two centuries after Queen Joan was imprisoned, a castle would again contain the power of witches. In 1612, ten people convicted of witchcraft were held in Lancaster Castle soon to be facing the gallows. Their crimes included laming, causing madness and what was termed ‘simple’ witchcraft as well as sixteen unexplained deaths stretching back decades. Those accused included members of two major families which were headed by older widows, including Elizabeth Southernes and her two children, Elizabeth and James, and Anne Whittle and her daughter Anne Redfearne. Others were dragged into the affair: John and Jane Bulcock (a mother and son) Alice Nutter, Margaret Pearson, and Katherine Hewitt were all also involved in the trial as co-conspirators.

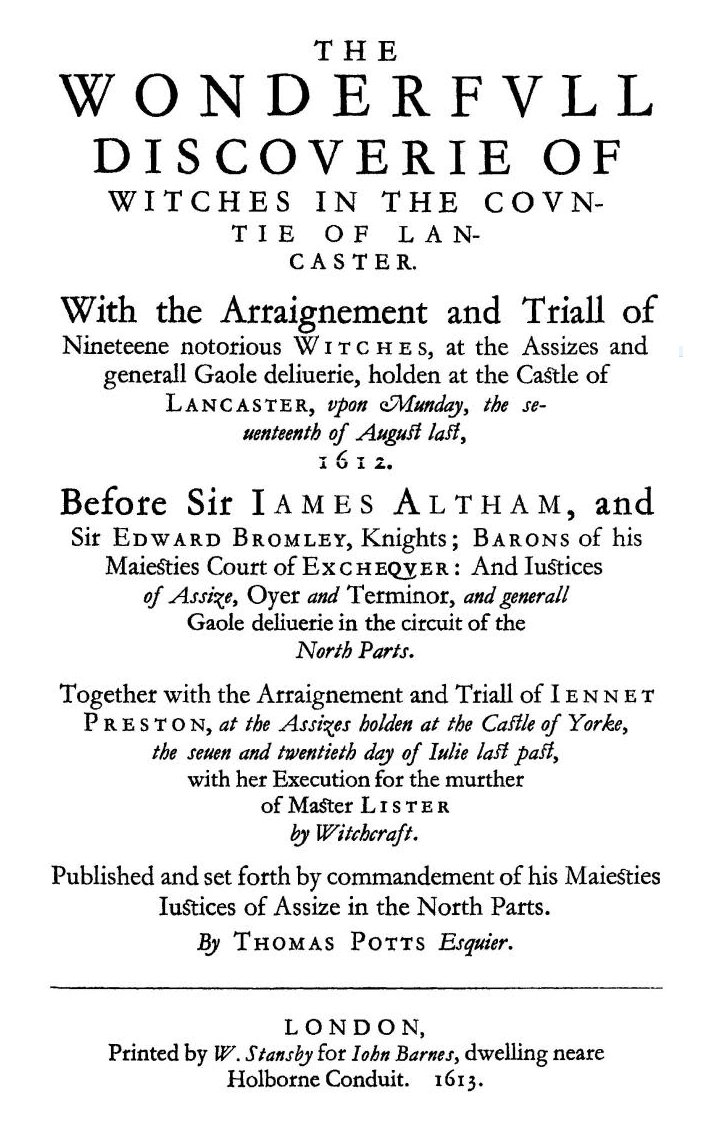

Five of the ten people were tried at the castle itself with Judge Bromley presiding, accompanied by Judge Altham. The judges were assisted by Lord Gerard and Sir Richard Hoghton. The prosecutor was a former high sheriff of Lancashire, Roger Nowell, and the clerk of the court was Thomas Potts of London. A year later, Thomas Potts published his account of these events in a book entitled: The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster. Potts chose to dedicate his book to Lord Knyvett, the man who had arrested Guy Fawkes in 1605; the Gunpowder Plot still a fresh memory for many across the country. The political and religious atmosphere played a clear role in the prosecutions and convictions of those imprisoned in Lancaster Castle in 1612.

The Pendle witch trials, like the imprisonment of Queen Joan, were bound up in the political, religious, and economic turmoil of the period. The role that the castle played in these persecutions may seem minimal at first glance; however, the power and significance that they held in these situation needs further investigation. The stone walls were thought strong enough to contain the magic that these people were accused of conjuring and that in itself is telling in terms of the force castles held in the minds of society. Castles did not only need to keep people out, but they were also used to keep people – and magic – from escaping.

[1] Rot. Parl., IV. 1186.

[2] Chronicles of London, ed. by C.L. Kingsford (Oxford, 1905), p. 73; Chronicle of London, 1089-1483, ed. by N.H. Nicolas and E. Tyrell (London, 1827), p. 107.

[3] See ‘The Captivity of a Royal Witch’ for the printed household account.