Excavation Director, and lead archaeologist for the past two decades in the investigation of Clavering Castle sets the scene for what they hope to find over the the next three weeks.

Norman knights fleeing the forces of Earl Godwin of Wessex coupled with miraculous encounters between King Edward the Confessor and St John the Evangelist form just part of the shady historical drama hidden behind the leafy tranquillity of Clavering Castle in north-west Essex.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

The scheduled site of Clavering castle is recognised as a rare example of a castle established in Anglo-Saxon England before the Norman Conquest. The castle has been subject of a twenty year programme of detailed historical and archaeological research by the Clavering Landscape History Group. This summer, archaeologists led by Simon Coxall of Warboys Archaeology Group, under a consent granted by Historic England and supported by the Castle Studies Trust, have a unique opportunity to explore by excavation this mysterious and previously unexcavated site.

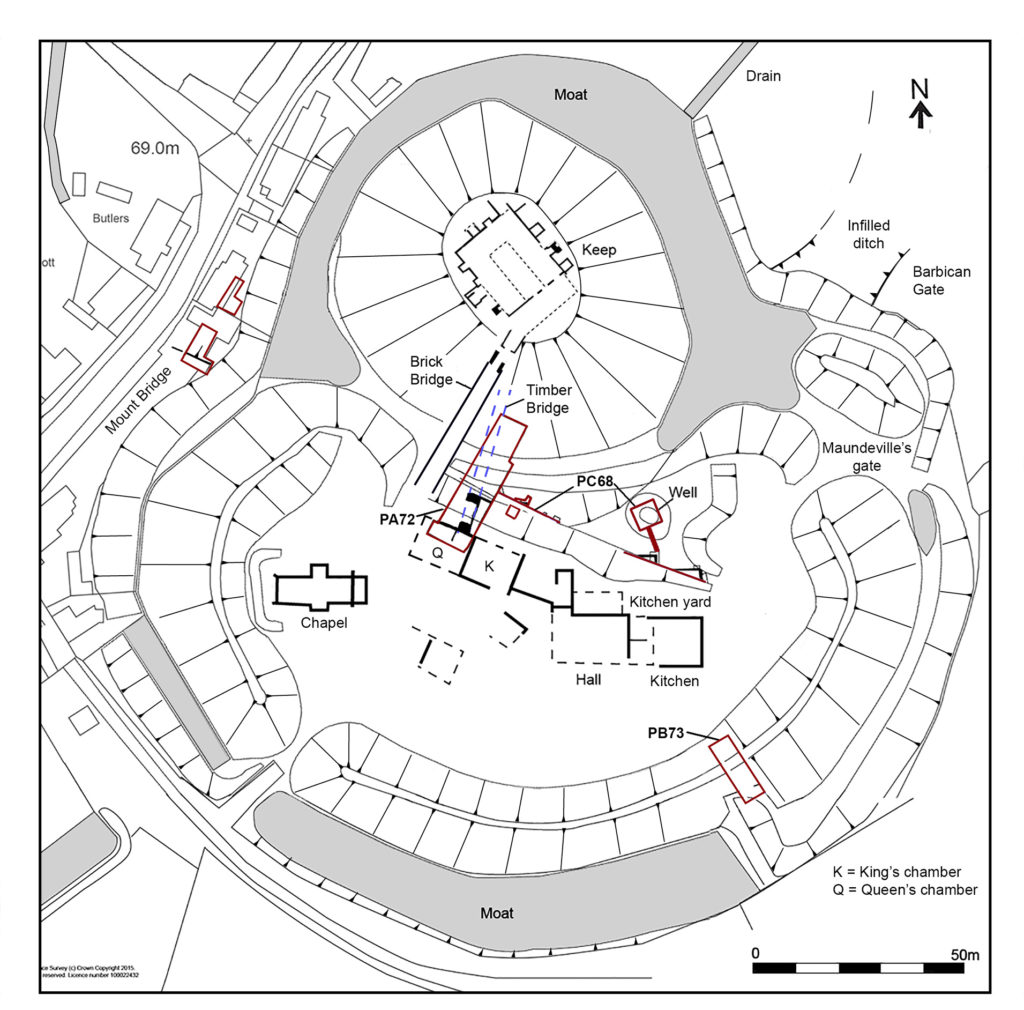

The castle platform which is entirely man-made is surrounded on all sides by imposing moated defences c4m deep and sits in the valley of the river Stort which evidence suggests witnessed significant diversion and management of its river system to accommodate the estate.

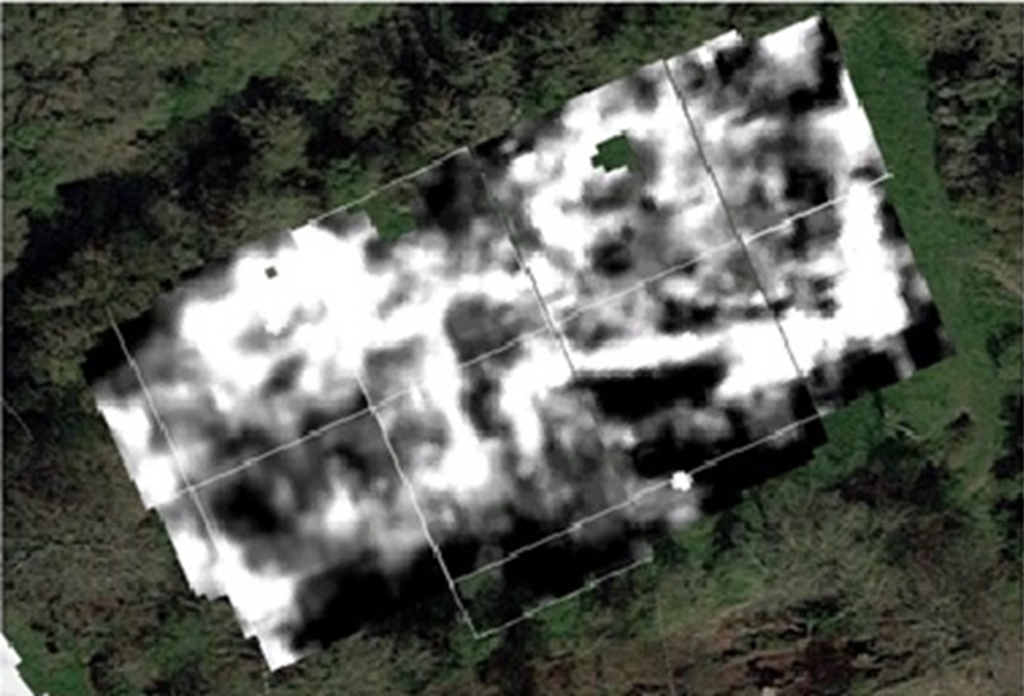

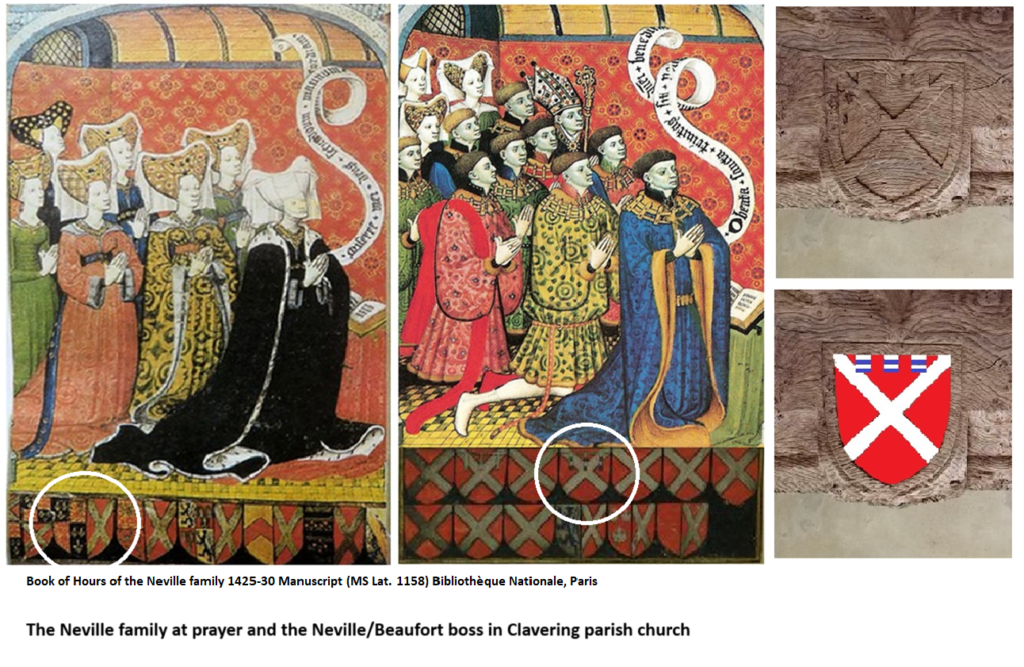

Geophysical survey suggests structures occupying twin courtyards once existed spanning across the sub-rectangular platform which measures c100m x 60m. The Castle platform abuts the parish churchyard to its south. Here further geophysical survey suggests the location of the now ‘lost’ chapel of St John the Evangelist which bore witness to Edward the Confessor’s aforementioned ‘Miracle of the Ring’. The twin courtyards appear connected to one another by an entrance court which issued out onto a bridged crossing of the moat connecting the castle with the family chapel where the alleged miracle occurred. It is suspected the geophysical evidence primarily relates to the powerful Neville family’s reconstruction of the castle site in the later 14th century, although some more ephemeral readings hint at the presence of earlier structures.

The Nevilles were arguably the most powerful baronial family in England during the 15th century and were through their marriage alliances with the Plantagenet royal family at the forefront of the dynastic conflicts now known as the Wars of the Roses. Clavering was selected by the Nevilles as their southern caput, these notorious northern lords presiding over their lordship and hundred of Clavering lying just a day’s ride from London. Clavering castle was successively held by the Neville Earls of Westmorland, Richard Earl of Salisbury, Richard Earl of Warwick and, through his Neville wife, George Duke of Clarence, the executed brother of the Yorkist kings Edward IV and Richard III. With the fall of the house of Neville the castle was seized by the Crown and stayed a crown possession until it was granted back to effectively the last Neville lord of Clavering – Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury (1473-1541) Though she refurbished elements of the castle and chapel in the 1520’s, as a devout Catholic and one of the last surviving scions of the Plantagenet royal family she too was executed on the orders of Henry VIII in 1541.

Beneath the levels denoting the Neville tenure of the lordship, archaeologists are hopeful of encountering earlier evidence of the de Clavering and FitzWymarc occupation of the castle. The de Claverings were, like the Nevilles, powerful lords of the north who feature extensively as Magna Carta sureties and later campaigning knights under Edward I and Edward II. With Robert FitzWymarc (c1030-1075) we return to the pre-conquest evidence that promises to push the history of the site back a thousand years to the dying days of Anglo-Saxon England.

This summer’s excavations will initially focus upon the key area around the entrance court connecting the castle platform with the adjacent churchyard. Such will seek to explore the entrance court and bridged crossing, the various phases involved in their construction, the materials used and its status, whilst testing the geophysical responses.

Digging deeper still, in the same key area archaeologists are hopeful of exploring the earliest evidence for the construction of the castle platform as revealed by the layers underlying the later medieval structures on site. In doing so fresh light will be shone upon the earliest days of castle construction in medieval England.