Heidi Richards, doctoral research at Durham University, looks at Pendragon Castle and how medieval romance literature impacted later medieval castle building.

Since childhood, I’ve been fascinated by castle ruins, stories of King Arthur, and a golden age of chivalry that existed somewhere back in time between history and fantasy. Fast-forward twenty years, and I’m currently finishing my doctoral thesis looking at the impacts medieval romance literature had on late medieval English castles.

Former arguments in castle studies subjected castles into a martial vs. status dichotomy, but current research embraces the duality of these aspects of the castle, providing space to explore possible symbolisms built into castle architecture and wider landscapes.

My research explores the importance of romance literature and legend within medieval society’s most elite, and through wills, commissions, dedications, and gifts, we find that romances were highly valued. Of primary importance though, was Geoffrey of Monmouth’s (c.1138) Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain). While not technically a romance, this work brought legendary heroes into an ancestral pseudo-history of the kings of Britain (including Constantine and King Arthur) and provided source material for romance narratives and characters. Many members of the elite alluded to this highly prestigious “ancestry” to legitimize and justify power, especially within the political propaganda and ambitions of Edward I.

Edward I was indeed an Arthurian “enthusiast” (as he has been called in previous research). He hosted many “Round Table tournaments” (more theatrical than regular tournaments and usually included Arthurian role-playing) to celebrate significant events, such as his Welsh victory in 1284. He exploited his “Arthurian ancestry” in a grand ceremony at Glastonbury Abbey in 1278 to reinter Arthur and Guinevere’s bodies—essentially conducting a spectacular funeral for Arthur, during which he used “Arthurian” relics (including Arthur’s crown) to legitimize his “inherited” power. He also wrote a letter to Pope Boniface in 1301 to claim land in Scotland on the basis that it was once owned by his ancestor, Arthur. A grand feast was also held at Westminster in 1306, during which Edward I swore oaths on a swan, in typical romance style, and knighted Edward II along with 267 others.

Every effort was made to continue Edward I’s Arthurian prestige and chivalric legacy when Edward II succeeded the throne. On his deathbed, Edward I charged his closest barons with assisting Edward II as his reign began; one of whom was Robert Clifford, who organized an enormous, chivalric celebration for Edward II’s coronation in 1308.

Edward II soon began to show that he was not the chivalric king his father was, staunchly contradicting the values of Edward I’s chivalric legacy. Records claim that he enjoyed working in the garden (which was uncustomary and inappropriate for a king), he didn’t like hunting, he didn’t participate in tournaments, and he thoroughly annoyed the barons with his infatuation over Piers Gaveston. As baronial unrest and tensions increased, we begin to see Arthurian allusions made by Edward II’s principal opponents—the same ones closest to Edward I.

This brings us to Pendragon Castle (Cumbria, previously Westmoreland), inherited by Robert Clifford as the “castle of Mallerstang,” along with other nearby castles, including Brough, Brougham, and Appleby. Clifford renovated Brougham and Pendragon Castles in preparation to host Edward I during the Anglo-Scottish wars in 1300, but whilst his other castles were renovated in contemporary architectural styles, Pendragon retained its archaic image. Architectural archaism was a trend in castle construction, used to symbolise continuation of power and ancestral prestige. In 1309, Clifford was granted a license to crenellate, changing the “castle of Mallerstang’s” name to Pendragon Castle.

In 1312, Guy Beauchamp, 10th Earl of Warwick, presided over the trial of Piers Gaveston, whose greatest crime, according to the commemorative Warwick ancestral “Rous Roll” (c.1484), was stealing King Arthur’s round table. The Earls of Warwick already had long-standing connections with Arthur and displayed romantic “relics” inherited from their “ancestors.” Robert Clifford and Thomas Lancaster also participated in Gaveston’s trial and execution, and in 1322, Lancaster signed a treasonous document to James Douglas in Scotland under the pseudonym “King Arthur.” In 1327 and 1328, Roger Mortimer, the lover of Edward II’s queen, Isabella, celebrated the marriages of his children by hosting multiple Arthurian themed Round Table tournaments in the style of Edward I, each lasting several days and sparing no expense.

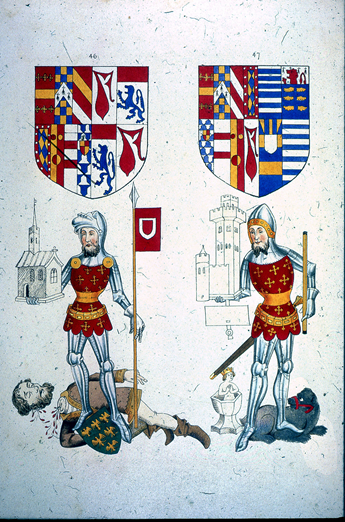

1845 edition of the Rous Roll, images 46 (left) showing Guy Beauchamp, 10th Earl of Warwick standing over the executed Piers Gaveston, and 47(right) shows his son, Thomas, portrayed with silver cup—heirloom relic of the fictional Swan Knight. The c.1484 original (British Library MS 48976), includes a caption below Guy’s image accusing Gaveston of selling “out of the land the round table of silver that was King Arthur’s and the trestles…”

Link to Guy Beauchamp’s image in the Rous Roll (c.1484) British Library MS 48976

https://imagesonline.bl.uk/asset/143267

In the wake of Edward I’s chivalric legacy, those who were closest to him (including Clifford, Warwick, Lancaster, and Mortimer) developed ways to emulate Arthurian prestige in their opposition to Edward II, and it is within this context that Pendragon Castle comes into view as one of several homages to King Arthur, Edward I, and the not-so-distant golden age of chivalry.