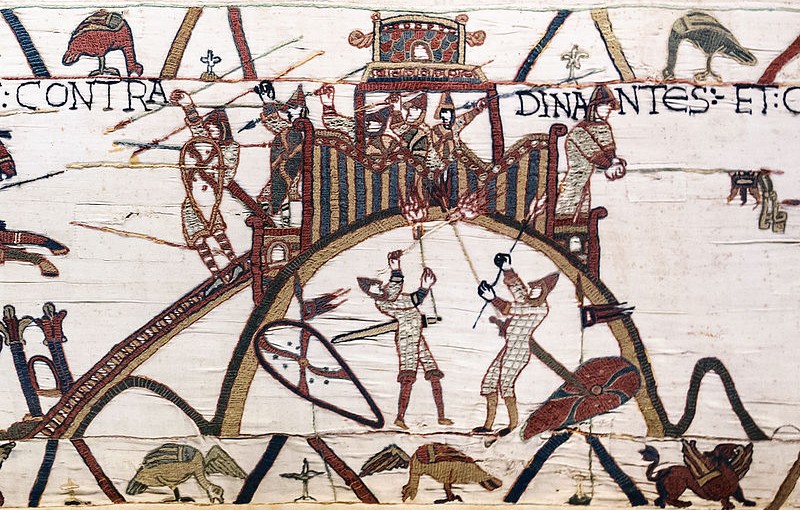

The only date in British history everyone remembers is 1066, when, on 14 October, William duke of Normandy defeated and killed Harold, king of England, and began a new era in this island’s history. Those interested in the castle know that it was William’s followers who brought it with them. 950 years on, it may come as a surprise to hear that what we know about castles built by the Norman conquerors in the years after 1066 is less than what we still don’t know: castle studies still matter and the work of organisations like the Castle Studies Trust is vital in encouraging better understanding of these monuments, and our own past.

Before 1066 the only castles in England were a handful built by Norman nobles who had been favourites of king Edward the Confessor. English nobles used a different type of residence and we will never know if they would eventually have followed the continental trend.

The Norman conquest did not end on 14 October 1066, it only began. William had wiped out the English royal family and much of the aristocracy but the battle of Hastings (and subsequent surrender of Dover and London) only secured him control of the south east. He then faced and defeated resistance and rebellions including that of Hereward “the Wake” in the Fens, while the people of York destroyed the first castle built there by the invaders in 1068 leading to the infamous “harrying of the north” in 1069. To understand the building of early Norman castles it’s important to bear in mind that the conquerors could not relax and believe they were secure for a number of years.

Castles featured from the start. From the quickly fabricated timber palisades put up to protect the army when it landed to the foundation of the new “Tower of London”, William ordered the construction of royal castles while also encouraging the bishops and nobles who had followed him to build their own. Many great stone castles standing today were originally put up as earthworks in the years immediately after 1066. In turn, the great lords who replaced virtually the entire English ruling class encouraged their own followers to secure themselves in their own castles. We don’t know the reasons why each was built: sometimes sitting on the previous owner’s (unfortified) hall, the new castle was evidently a visual statement confirming change of ownership, but may also reflect concerns about security by the new landowner, living among and exploiting a much larger peasantry speaking another language.

The larger castles have been well studied. The lesser ones have not. There are probably at least a thousand earthworks in what was then England, most of which have never been excavated, never dated, their function only guessed at. Many are called “mottes” with no more evidence than that they look like one. The old certainty that all Norman castles were originally of motte and bailey design has been replaced with awareness that the recognisable conical mound forming the motte was sometimes added later to a simpler enclosure defined by a ditch, rampart and palisade. The bailey too is proving more complex: why did some castles have two (or more), why are some so vast? Some now seem to have enclosed whole villages, others are too cramped for any but the smallest buildings. The CST-funded project at Caus (Shropshire) tackles this question.

950 years after William began the conquest of England, we are asking questions about Norman castles based not on old prejudices about what castles were, but on historical and archaeological study based in a better understanding of the reality of eleventh and twelfth century societies.

Dr. Peter Purton