Phase Two excavations at the putative partial ringwork castle at Lowther (Cumbria) will get underway on Sunday 12th May 2024. The project team leaders Drs Sophie Ambler and Jim Morris look at one they found in season one and look forward to what the want to will be examining in season two.

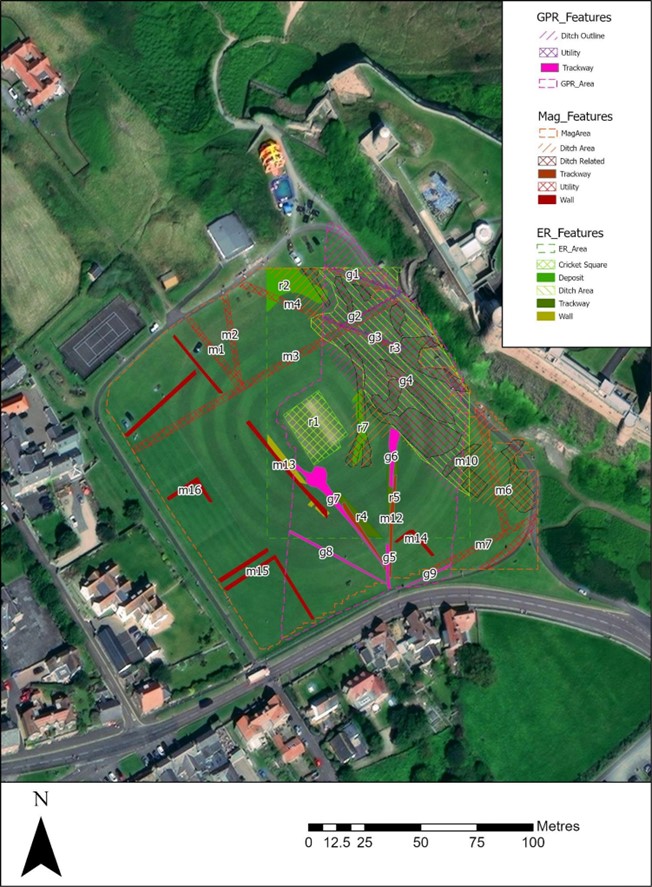

The Lowther Medieval Castle and Village Project unites History and Archaeology through Lancaster University, the University of Central Lancaster, and Allen Archaeology, with the support of Lowther Castle and Gardens Trust and the Lowther estate team. Phase One excavations in summer 2023, generously funded by the Castle Studies Trust (CST), saw a geophysical survey of Lowther’s north park and excavations of the ‘castlestead’ earthwork. Phase Two will see further excavations of the castle earthwork, funded by the CST, and a geophysical survey of the area to the north, funded by the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society (CWAAS).

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

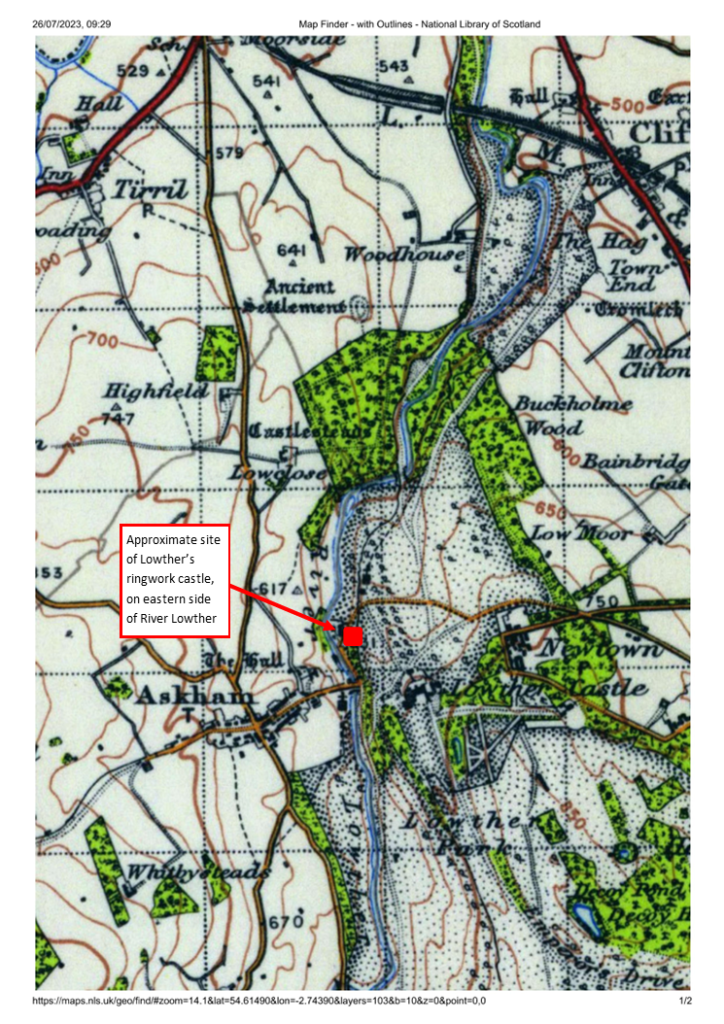

The site at Lowther is potentially of great significance for castle studies and the medieval history of Britain. We have good reason to think the site is associated with the second phase of the Norman Conquest: the annexation and plantation settlement of the Kingdom of Cumbria under William Rufus in 1092.

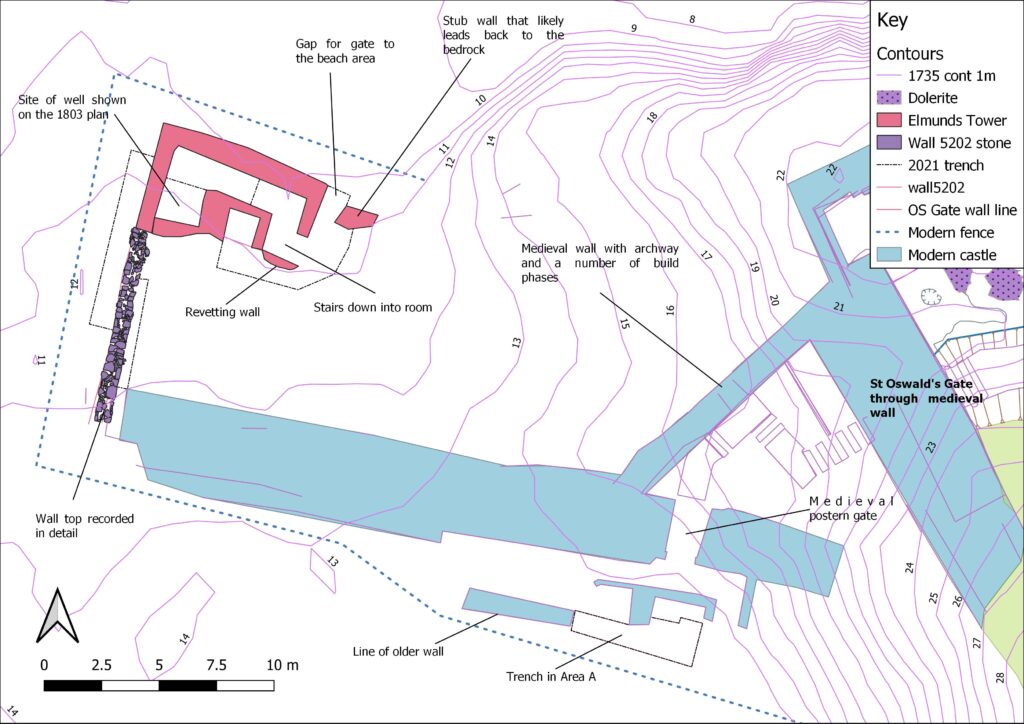

Thanks to the 2023 excavations and their interim report, we can begin to investigate how Lowther sits within ringwork castle typology. This is a partial ringwork, sited on the edge of a promontory, its banks built up on the landward sides. It thus took advantage of its landscape to be seen and to see. This conforms to a model for castle siting that aimed to produce (in the words of Oliver Creighton) ‘a conspicuous symbol of power with a panoptical viewshed over the surrounding territory’. At approximately 27m X 22m, Lowther sits at the smaller end of the ringwork spectrum. In that its central area is raised above external ground level, with landward circumferential banks elevated further, it bears comparison with ringworks of Norman Ireland.

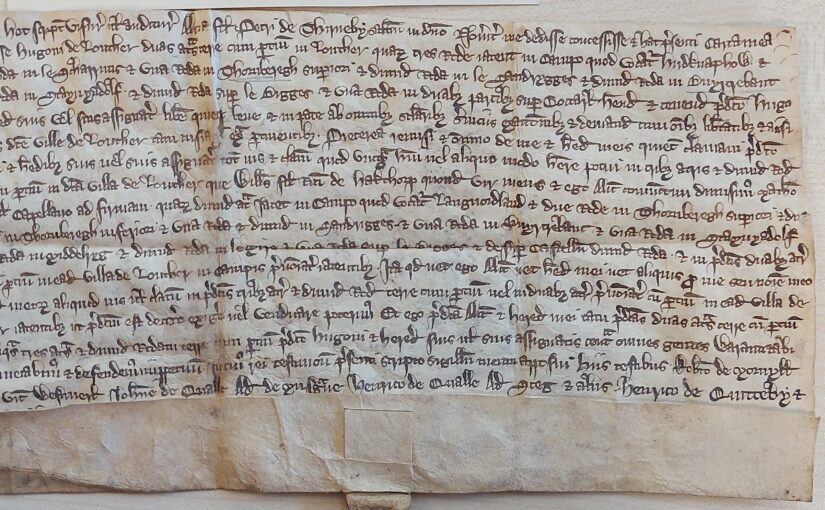

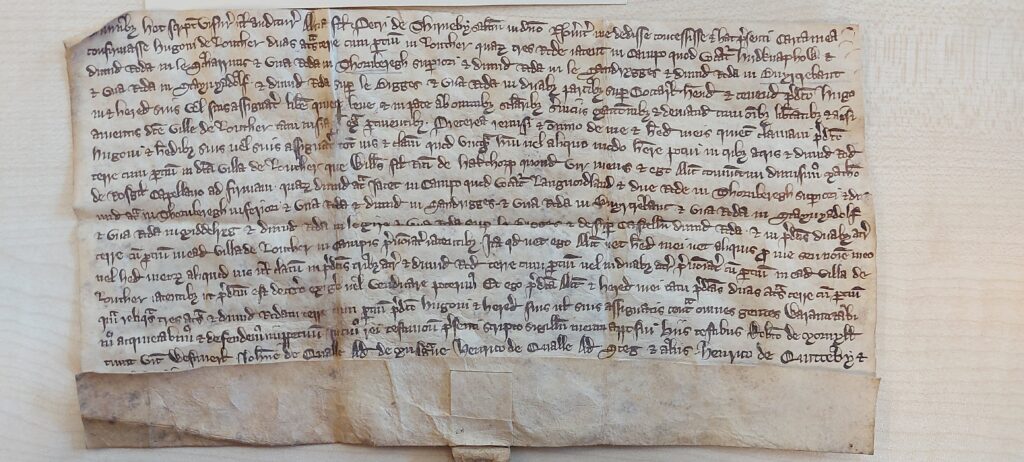

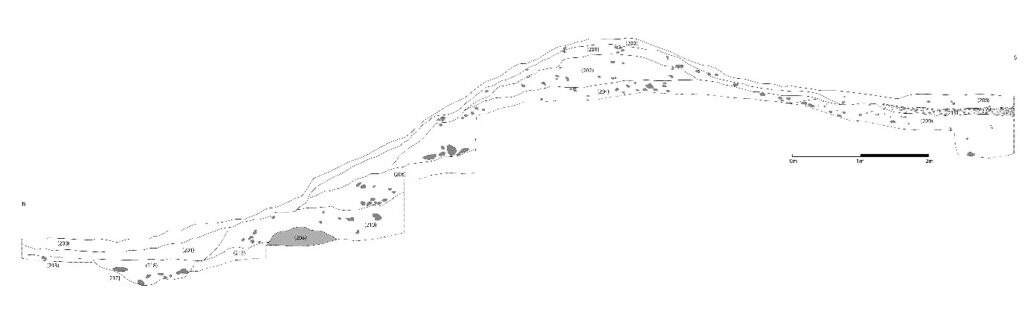

Trench Two investigated the construction of the castle’s north bank. This was one of our biggest undertakings in 2023: the trench measured 15m north-south, and 1m east-west, cutting through the northern bank, all excavated by hand. It was certainly worth the toil. A large block of limestone appears to represent the first layer of the castle’s construction; this is followed by at least four separate building deposits. Seemingly the bank was built up from a number of earthen layers with some smaller stone layers incorporated into the bank, perhaps for stability.

The trench’s southern part, within the castle interior, was also revealing. The stratigraphy, together with the clear level difference between the interior and northern exterior of the castle, suggest how the castle was constructed, first with a great mound, then with bank layers added around the northern, southern, and eastern banks to create the partial ringwork. No evidence has yet been found of a fosse associated with the castle, although Trench Two revealed a small feature at the far north of the trench, of a silty fill cut into the subsoil, running east-west (with a north-south width of 1.52m), possibly a drainage ditch the filled up gradually.

Trench Four began to uncover the castle’s entranceway, in a break in the eastern bank. The removal of topsoil and subsoil revealed a metalled surface, comprising river stones ranging from 0.04 to 0.11m, between 0.20 and 0.15m deep. This seems to be the metalled interior surface of the castle, starting at the entranceway.

Our 2023 excavation yielded little in the way of small finds, although this is not unusual for medieval Cumbria, and may also suggest that the castle was not long occupied. Meanwhile, in the hopes of finding good dating evidence, bulk soil samples of 40 litres (or 100% of a deposit if less was available) were taken from potentially datable features and layers for flotation for charred plant remains and for the recovery of small bones and artefacts. Bulk soil samples were processed using standard water flotation at the University of Central Lancashire. The results will be incorporated in the project’s final report.

Phase Two excavations will go further in investigating the castle’s construction – this time focusing on the interior. Can we identify a gatehouse structure? A potential comparator for Lowther is Castle Tower, Penmaen (Glamorgan), a partial ringwork sited on a promontory, of similar size and likewise with an entranceway gap: excavations here revealed a substantial Norman timber gatehouse, supported by six posts, and fosse. Phase Two will thus excavate an extended area over the entranceway and beyond. And can we identify interior structures (such as the small timber hall evidenced at Penmaen)? Phase Two will open a substantial area – a quadrant of the interior – to reveal the metalled surface, aimed at identifying postholes as well as maximising chances of recovering small finds.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Meanwhile, a partner investigation will get underway in the area around St Michael’s church, just north of the partial ringwork. The castle, village, and Norman church of St Michael’s represent a typical configuration for a medieval manor. The presence of Hogback and other stone sculptures (c.700-1000) at St Michael’s hints at an earlier religious site: can this be established and, if so, what form did it take and how did the Norman settlement overwrite it? And how far did the medieval settlement, attached to the castle, extend northward? Building on our geophysical survey from Phase One, Phase Two’s geophysical survey, supported by CWAAS, takes in the surrounds of St Michael’s.

There is more information on the Lowther Medieval Castle and Village Project on the project website. The 2023 investigation was also featured on BBC2’s Digging for Britain (Series 11 Episode 1), available on BBC iPlayer. The May issue of BBC History Magazine also includes an article on the early medieval Kingdom of Cumbria, placing Lowther’s ringwork castle in its broader context.

Excavations will run on weekdays at Lowther Castle and Gardens from 13th to 31st May 2024. The north park, where our site lies, is free to access. Visitors are welcome! Entrance to the nineteenth-century castle and gardens offers further opportunities to explore the site’s history: the partial ringwork castle features in Lowther Castle’s new exhibition. Information on visits can be found on the Lowther Castle website.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

You can find the interim report of last year’s excavation here: Grants and Results 2023 | Castle Studies Trust