In September 2023, author, Neil Ludlow, with Phil Poucher of Heneb – Dyfed Archaeology (formerly Dyfed Archaeological Trust) carried out the first modern detailed survey of Picton Castle, Pembrokeshire, funded by the Castle Studies Trust. Neil Ludlow looks at what they found in this unique and enigmatic building.

Picton Castle in Pembrokeshire has long been something of an enigma. It has a unique layout – there’s no other castle quite like it – which has been much discussed, resulting in rather more questions than answers. And it’s been continually occupied since it was built, so it’s seen a lot of alteration. While outwardly it retains much of its medieval flavour, the interiors were extensively made over during the eighteenth century so that it now presents itself first and foremost as a Georgian country seat. But beneath this veneer, much medieval work still survives – though a lot of it is tucked away behind stud-walls, in cupboards, or is otherwise obscured. Yet no structured archaeological survey of the castle had been undertaken, while the documentary record for its medieval development is more or less non-existent. We don’t even know its precise date – it’s long been attributed to Sir John Wogan, an important official in Crown service and Justiciar of Ireland 1295-1313, but being baronial work it’s unlike Crown work where accounts usually survive.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

To try and resolve some of its many mysteries, the Castle Studies Trust generously funded survey, recording and research at the castle during 2023, which was carried out by the author, Neil Ludlow, with Phil Poucher of Heneb – Dyfed Archaeology (formerly Dyfed Archaeological Trust). A full photographic record was made, along with a full 3-D survey using a Leica RTC360 laser scanner. This was not without its challenges. The castle is still occupied, as the administrative hub for the Picton Castle Trust, which means that many areas are busy, working spaces, while others are used for storage – and nearly all of it is furnished.

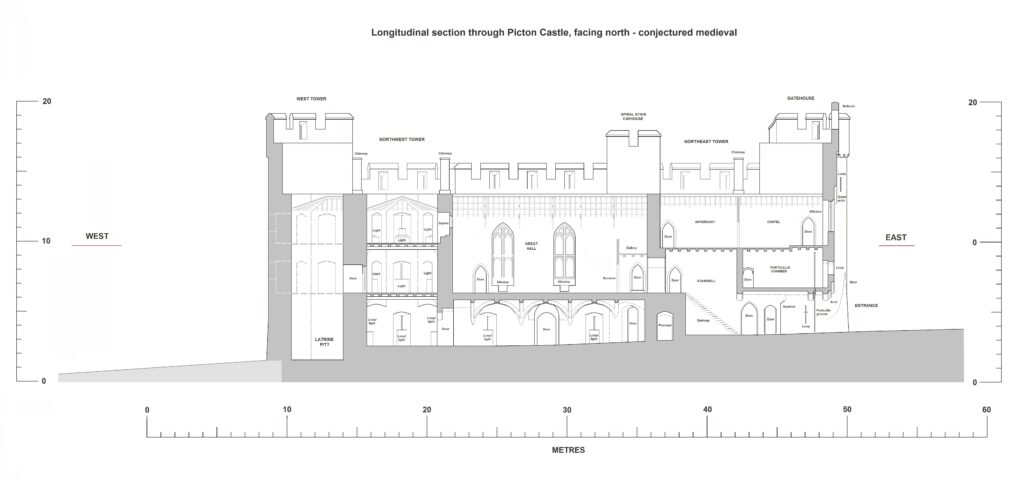

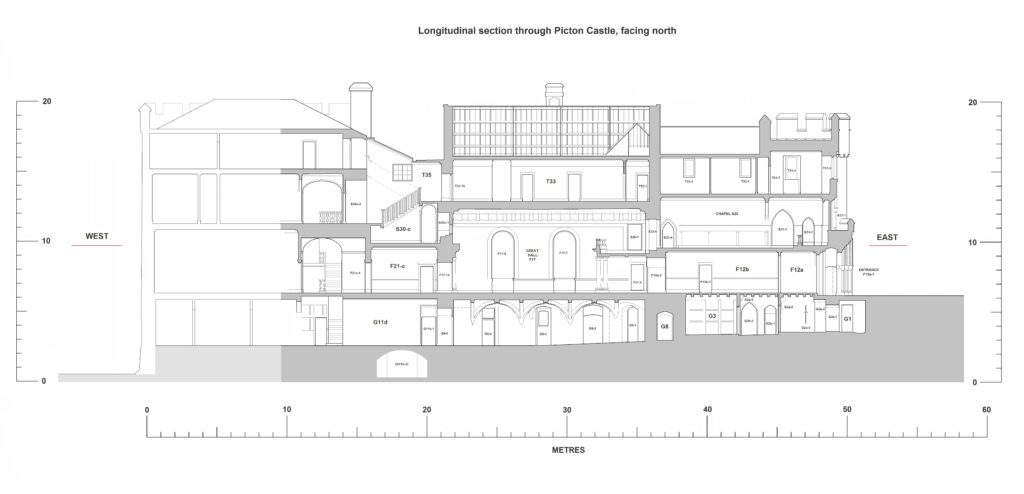

Picton’s unique layout makes it a castle of great importance. Most castles have at least some close parallels, but Picton is effectively one of a kind. In essence, it is a towered hall-block, inviting comparisons with castles like Nunney in Somerset, and the ‘towered keeps’ of thirteenth-century Ireland, for example at Carlow and Ferns. However, close study shows that it resolves as a central first-floor hall, flanked by services and a chamber-block to form a very early example of the three-unit ‘H-plan’ house. Here, though, the end units are processed out as D-shaped towers, two on each side wall. A terminal twin-towered gatehouse lies opposite a D-shaped tower formerly lying at the western apex – seven towers in all. The hall is open to the roof; the towers have polygonal interiors (two of them disguised beneath later fittings), and contain three storeys. The ground floor is mostly rib-vaulted. The gatehouse – unusual in buildings of this kind – led onto an equally unusual ‘grand stairway’ to the hall; a second ground-floor entry probably led to an external kitchen and bakehouse. Though very forward-looking in its layout, the castle belongs stylistically to the first two decades of the fourteenth century, and analysis of the sources suggests that it was most likely built by John Wogan between around 1315 and 1320.

The castle’s spatial disposition, access and circulation are meticulously planned, while the domestic appointments show a remarkable level of sophistication for the period, including what appear to be vertical serving-hatches between the ground floor and the service rooms above. At second-floor level, the east towers and gatehouse form two integrated suites of residential apartments either side of a chapel, in a manner firmly rooted within royal planning. The opposite pair of towers, at the west end, seem to have been united internally to form a residential chamber-block, for Wogan’s officials and guests, possibly served by latrines in the former west tower; the present partition walls are later.

Some aspects of the layout may show influence from northern Britain, or perhaps even Plantagenet Gascony. Detail shows influence from the castles of Gilbert de Clare, including the form of the spur-buttresses, the rib-vaulting and the arrow-loops. Execution of the design is however largely regional, showing great ‘plasticity’ of form and extensive squinching. There is surviving evidence for neither a defensive ditch, nor a surrounding wall until the seventeenth century, though an accompanying enclosure – containing the kitchen and other ancillary buildings – is likely from the first.

Beginning in around 1700, and spanning over 50 years, extensive works transformed the castle into an elegant country house, with magnificent and well-preserved Georgian interiors that include what seems to be only the second circular library to be built in Britain. Later campaigns included the addition of further wings and ranges. Work continued into the later twentieth century, with an extensive refurbishment in the 1960s. But the earlier work has largely survived, making the castle – along with its gardens – a popular visitor attraction.