The Castle Studies Trust have awarded five grants totalling £35,000 to support research into castles. This is a record amount for the Trust, and as we enter our tenth year as a charity, we could not have managed this without our supporters.

We will bring you updates from these projects throughout the year as the teams get stuck in. But first, let’s get to know them a bit better. They are from across England, Scotland, and Wales and take different approaches to understanding castles.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Bamburgh

Standing on a rocky outcrop on the coast of Northumberland, Bamburgh’s history stretches back to the early medieval period when it was home to a palace of the Kings of Northumbria. Bamburgh Castle itself was owned by royalty at various points, and rebuilt in the 18th century.

Bamburgh is a massive site: its history has been illuminated by excavations, and there is still more to learn.

Dr. Joanne Kirton and Graeme Young of the Bamburgh Research Project plan to carry out a geophysical survey and a masonry survey of the castle’s outworks.

Dunoon

A castle at Dunoon was first mentioned in the late 13th century but may be older. The ruins visible today date from the 14th century. It stands on a hill on the coast of the Firth of Clyde. The castle was besieged and captured multiple times over its centuries-long history and became a royal residence.

Despite the castle’s royal links, little is known about its layout and dating. Dr. Manda Forster’s team at DigVentures will carry out geophysical surveys (resistivity and magnetometry) of the mound and the area around it to find out where there may be buried walls, foundations, or other archaeological remains.

They will also organise workshops for the local community to learn how geophysics work. So as well as learning more about the castle, they may inspire the next generation of archaeologists!

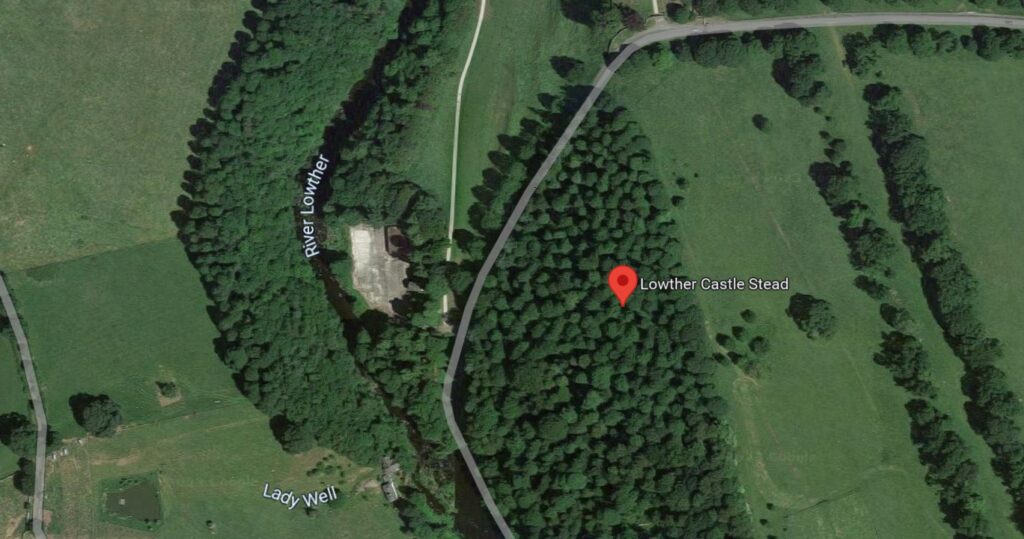

Lowther

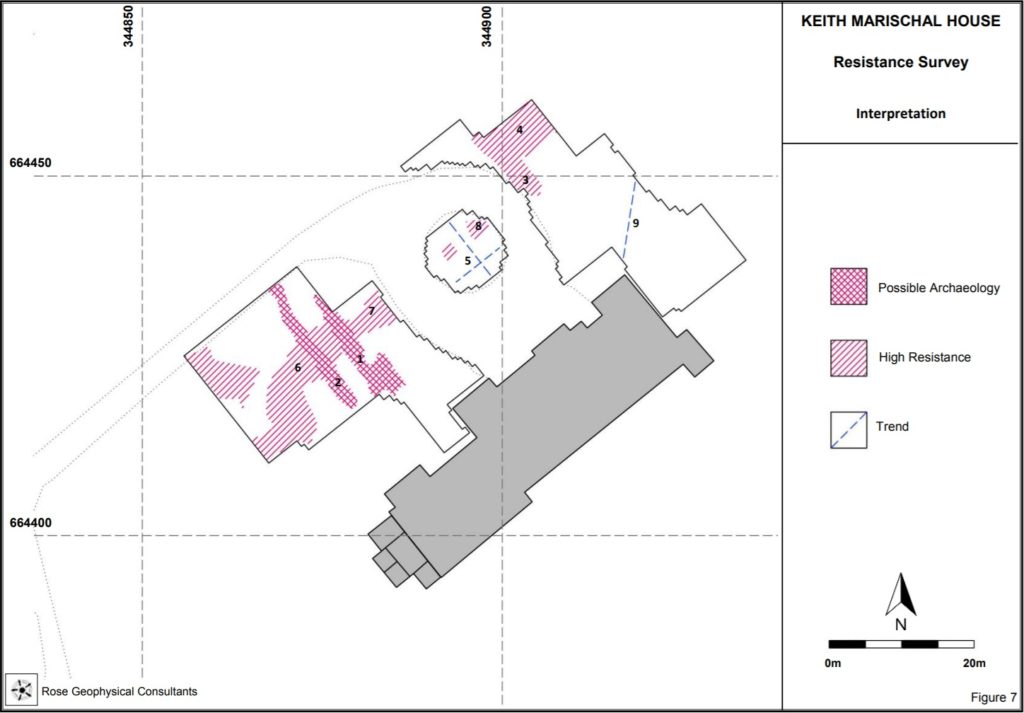

The present Lowther Castle was built in the 17th century, but a few hundred metres north lie the medieval remains of a castle and possible deserted village. Lancaster University Archaeology Unit surveyed the earthworks in the 1990s, but there has been no other archaeological investigation since.

Being able to date the site would be a crucial step in understanding the Norman influence in the region. Could this be part of the remains of the Norman conquest of the Kingdom of Cumbria in the late 11th century?

Dr. Sophie Ambler has devised the project to carry out geophysical surveys at Lowther Castle followed by excavations. Working with the University of Central Lancashire and Allen Archaeology, this aims to establish the site’s building chronology.

Picton

Pembroke’s Picton Castle is a medieval building with later alterations and additions. It is uncertain when it was built and by who, but it is likely to have been established in about 1300 by Sir John Wogan. Picton has an unusual layout but may have parallels with French medieval castles.

Neil Ludlow and the Dyfed Archaeological Trust will carry out a measured survey of the building, recording its structure and creating a photographic record of the site. This will be an invaluable resource to understand the site, and help show the castle’s development over the centuries.

Wigmore

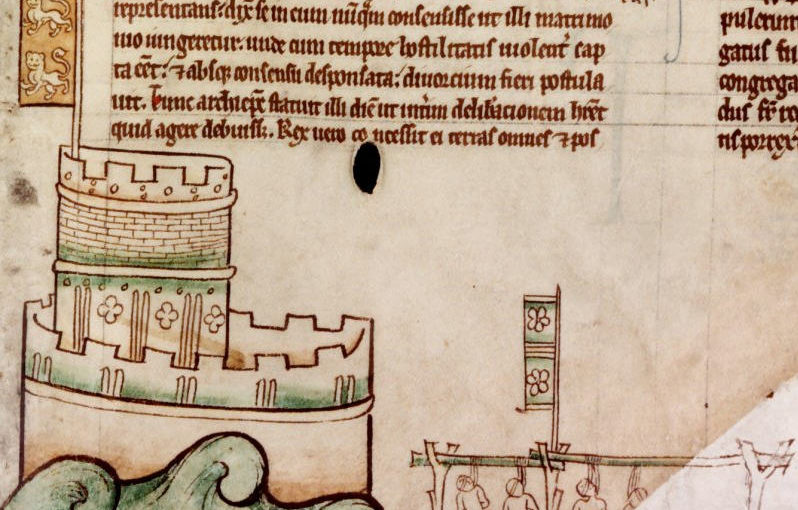

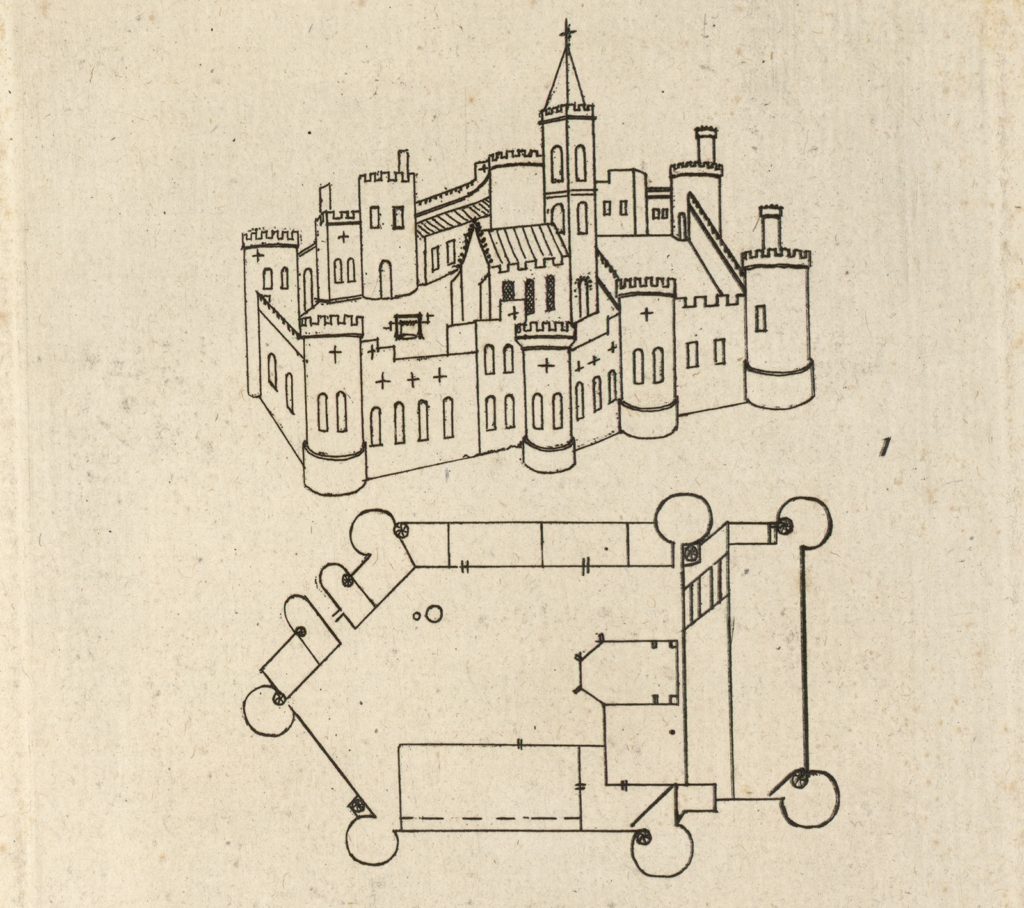

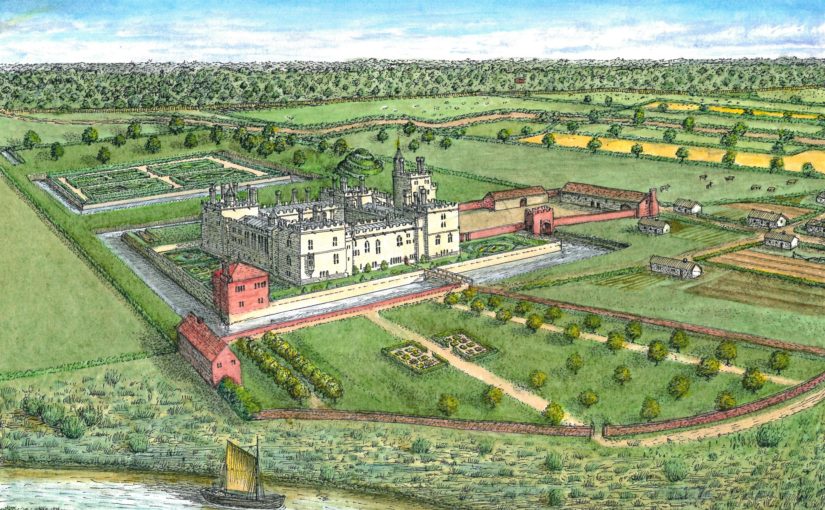

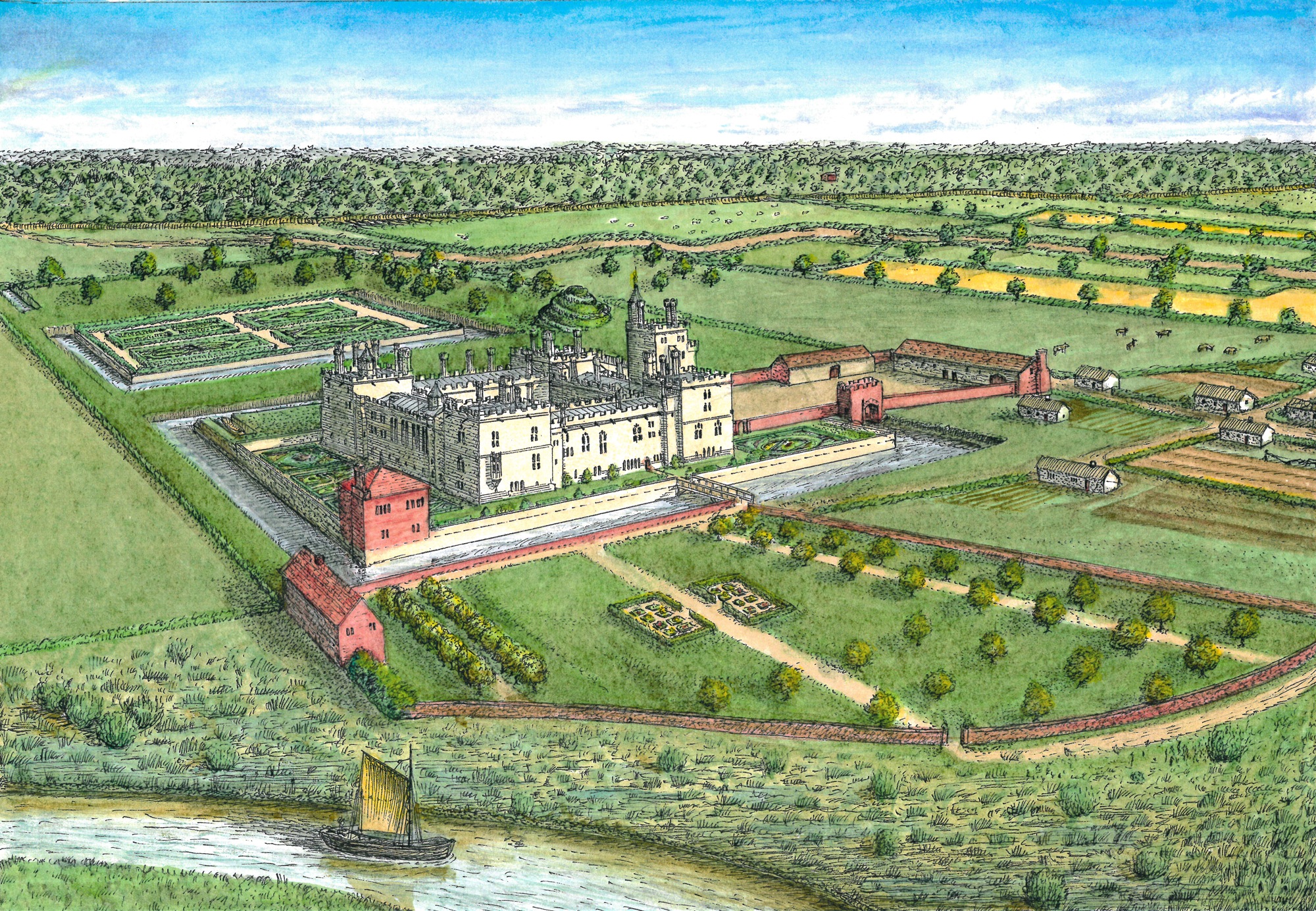

Wigmore was amongst the early castles established in England in the wake of the Norman conquest. It was founded by William Fitz Osbern, Earl of Hereford and later became the home of the Mortimer family. They were an influential family in the Welsh marches, and they developed the castle to reflect their growing power.

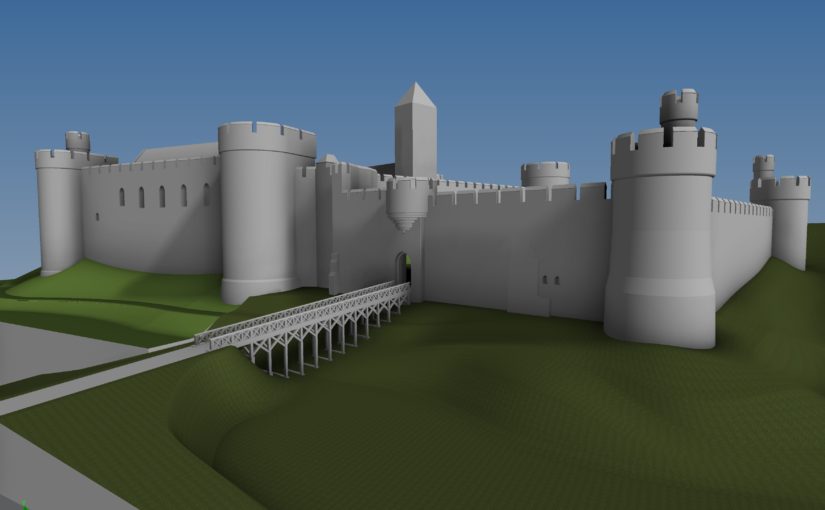

Small-scale excavations at Wigmore and geophysical surveys in the 1990s demonstrated the archaeological potential of the site, but what is missing is a reconstruction of how it looked during its heyday.

Chris Jones-Jenkins will create a reconstruction of how Wigmore Castle used to appear. This will draw on archaeological and historical sources to bring the reconstruction to life. You may also have seen Chris’ work with his reconstructions of Ruthin and Holt.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter to receive updates on these projects and our other ongoing work in the field of castle studies.

Header image: Bamburgh Castle by Michael Hanselmann via Wikimedia Commons, licensed CC-BY-SA 3.0.