When walking round ruined castles, it can be difficult to picture how they once were. There may be missing floors, the roofs aren’t the same, and entire buildings might have vanished. Even when a structure appears to survive intact, we are usually missing the interior – how it was decorated, the furniture, even how light changed throughout the day.

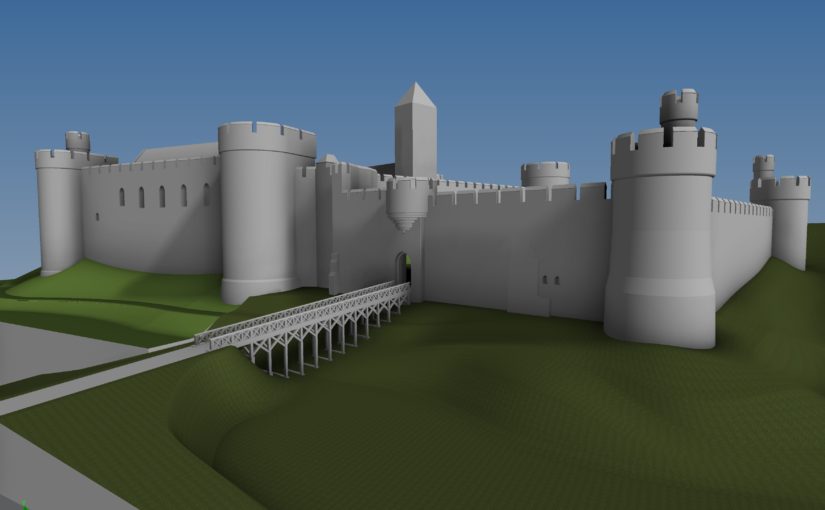

Reconstructions are a wonderful tool for bringing castles back to life. This year, the Castle Studies Trust is funding one such reconstruction. Chris Jones-Jenkins is helping us understand how Ruthin Castle would have looked. You might recognise his name from 2015, when he worked on one of our very first projects, the digital model of Holt Castle, or from his various work with Cadw and English Heritage.

We caught up with Chris to learn a bit about what goes into these illustrations and how he got into reconstructions. Older illustrations, like those done by Alan Sorrell decades ago, were done by hand while a lot of reconstructions today are done on a computer. Chris has experience of both, and they are very different processes. When working by hand, you need to start off by choosing your viewpoint and deciding what it is you’re going to show. With a digital reconstruction, you have the option to change the position of where you’re looking from. Chris reconstructs everything in the image and the viewpoint might be the last thing to be settled. With Holt for example, if that had been reconstructed 20 years ago the viewpoint would have been one of the first things decided – what to show, what to discreetly tuck away, and how to balance highlighting everything you want. Instead, as Chris created the whole thing digitally it was possible to use the model to create a flythrough video.

A wealth of information goes into reconstructions. For Holt and Ruthin, any standing remains are taken into account and modelled, while historical evidence such as paintings or documents are used to fill in the gaps where parts of the structure are missing. Chris trained as an architect and early in his career so has an eye for how buildings are put together, complimenting his skill as an artist and years of experience with historic buildings. Will Davies and Sian Rees have been helping with the research into Ruthin Castle and how it appeared, giving Chris the best information possible to work from. There was a survey of the curtain wall, but done to the wrong scale, which kept the team on their toes.

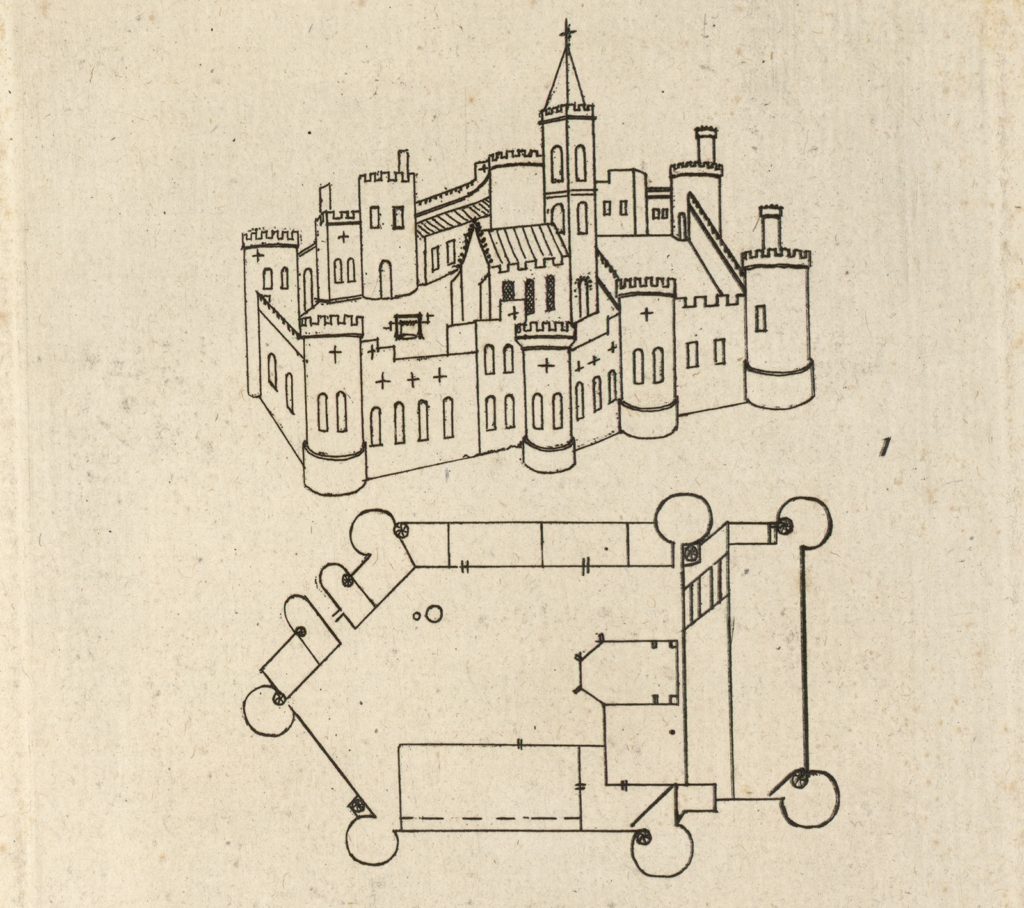

Working with some kinds of source material you get a feel for how useful and accurate it is. For instance, in the 17th century Randle Holme made some useful plans of Holt Castle in pen and ink. He also created a view of Ruthin Castle, but for some reason his work here wasn’t as reliable. The test is that the parts of the castle that still survive weren’t well illustrated by Holme, so his work needs to be used carefully.

A lot of time and effort goes into reconstructions. It can take over six months from start to finish, with drafting, redrafting, tinkering with details, and pausing to research a particular feature or issue. Over this time, the reconstruction grows from a plain model to a textured, colourful building. Reconstructions have an element of educated guesswork, but attention to detail is important. If you misstep and include something not appropriate for the period there are eagle-eyed heritage lovers who spot this kind of thing! New information is being uncovered about Ruthin, which directly informs Chris’ work. But there are some questions, like the forms of buildings, which are only likely to be answered by excavation.

Chris has been working on reconstructions since the 1980s, and aside from the change in technology has noticed an interesting trend. Previously, there was often emphasis on showing the structure while more recently the organisations commissions reconstructions want to populate these buildings, showing daily life inside.

Talking to Chris, one thing that cropped up is that reconstruction artists don’t often get to hear what the public think about their work which is a real shame as it can make a world of difference to a site. So when going round a historic site, if you see a reconstruction that captures your imagination or helps you understand the place better, pass on that positive feedback.

The image at the top of this page shows the a work-in-progress version of the reconstruction. Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter so you don’t miss news about the finished reconstruction and our other projects.