The deadline for grant applications passed on 1 December. We’re going through the various projects now. Altogether the 15 projects, coming from all the home nations and one from Ireland, are asking for over £110,000. They cover not only a wide period of history but also a broad range of topics.

We will not be able to fund as many of these projects as we would like. To help us fund as many of these projects as possible please donate here:

In a little more detail here are the applications we’ve received:

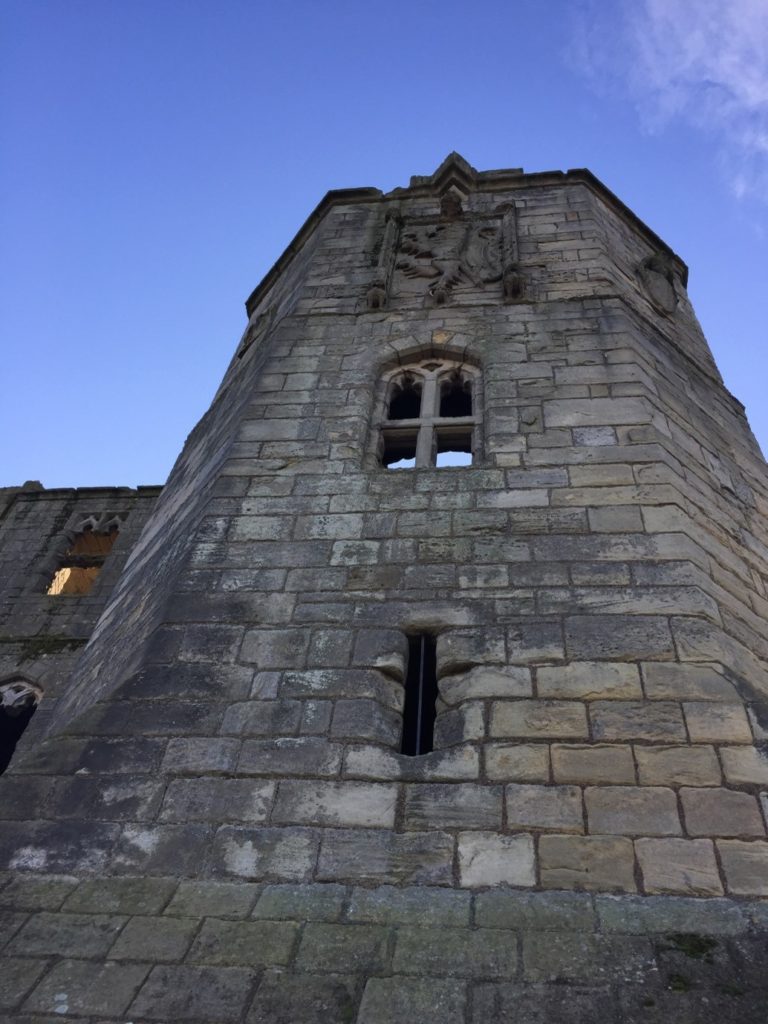

Bamburgh, Northumberland: The aim of the project is to better understand the outworks to the north of the castle, by using various geophysical survey techniques and a preliminary survey of the masonry remains, it will include a 3D model of the recently excavated Elmund Tower and provide materials for interactive displays.

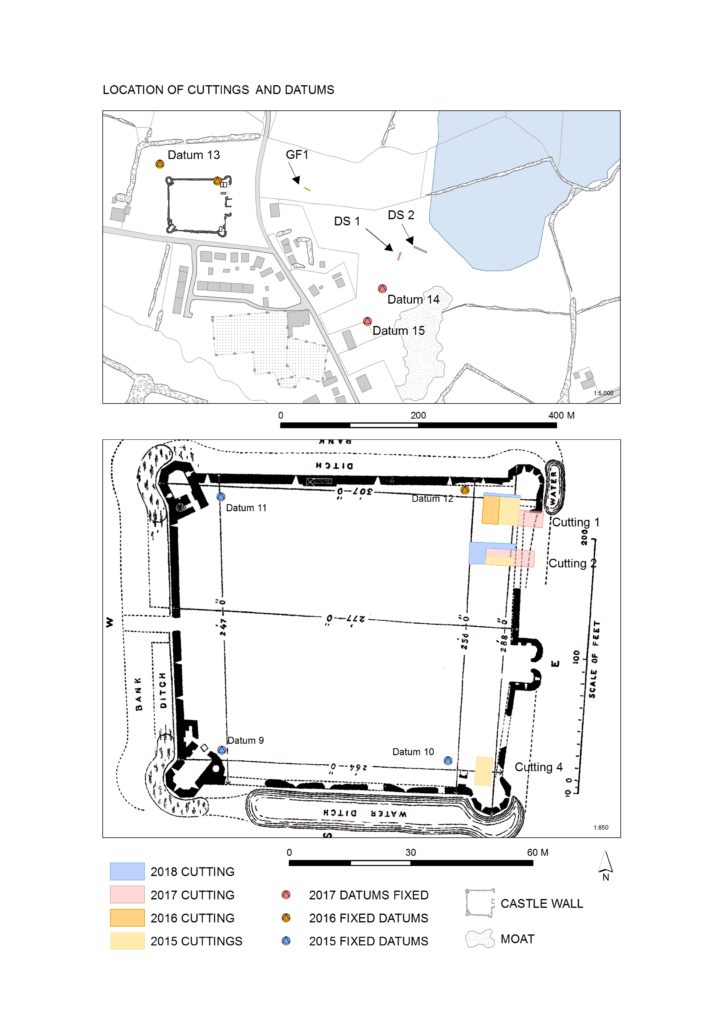

Barnard Castle, Co Durham: The aim of the project is to try and understand a lot more about the outer ward of the castle, using a variety of methods including geophysical survey, aerial survey and test excavation

Cavers Castle, Roxburghshire: Through a combination of building survey and excavation to try to understand the early form of this important baronial castle.

Dunoon, Argyll: A community-led geophysical survey project to understand better the form and scale of this important castle that was the seat of the Lord High Stewards of Scotland. The original castle dates back to the 1200s and the remains above currently ground date from the fourteenth century.

Fun Kids, Castle Podcasts for 7-13 Year Olds: To produce a series of 8 podcasts for children aged 7-13 to engage children to explore a what, how and why of 8 castles. The series will focus on a variety of castles and build awareness of less common castles that families can explore.

Galey, Co. Roscommon: Geophysical and topographical surveys to explore the possible motives behind the placement of, as well as immediate landscape context, morphology and any attached settlement and industrial activity, that occurred at a lakeshore-sited late medieval Gaelic-constructed tower house castle.

Hartlebury, Worcestershire: The seeks to explore what looks like a possible civil war bastion ditch, which seems to have been partially revealed in a 2022 drone survey of this former bishop’s palace with remains dating from the fifteenth century. This will be done through geophysical survey and excavation.

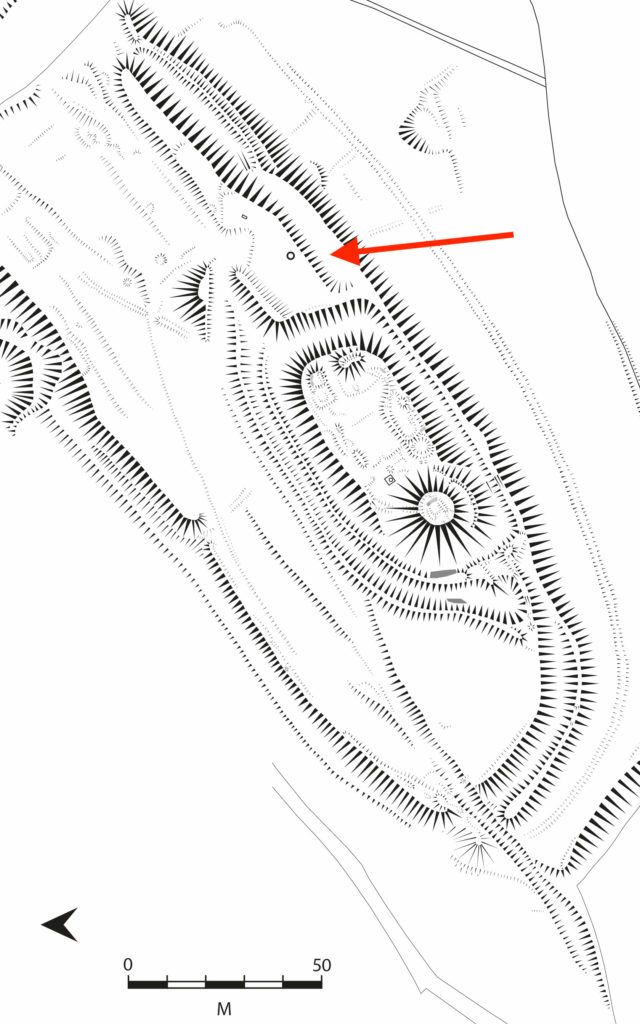

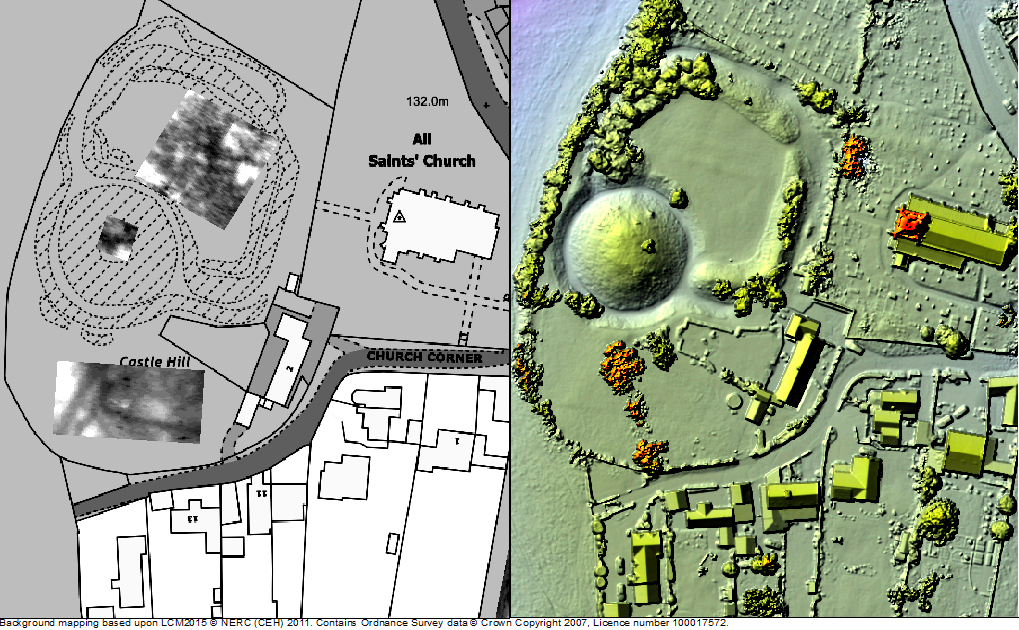

Lowther Castle, Cumbria: Through a combination of geophysical survey and excavation to try to learn more about this ringwork castle and settlement, thought to date from the late eleventh century. the aim is to try to discover if it dates from this period and was therefore a Norman plantation; and also its history after its foundation.

Millom, Cumbria: The project will involve a drone survey to assess the condition of the 14th century fortified manor combined with a geophyisical survey to understand if there is any link between it and the nearby church and monastery.

Muncaster, Cumbria finds assessment: To make a complete assessment of the finds from the 2021 excavations which took place near the 14th century tower along with two nearby kiln sites.

Muncaster, Cumbria geophys and archaeology survey: To carry out a geophysical survey of the area surrounding the castle and to investigate a large stone feature in the cellar of the castle to understand its purpose and possible date

Northern Frontier, Beacon Hill Yorkshire: A geophysical survey of Pickering Beacon Hill, a siege castle used for the siege of Pickering in the lead up to the Battle of the Standard (1138) to better understand the landscape at the time and see how much life was disrupted during the period known as the Anarchy.

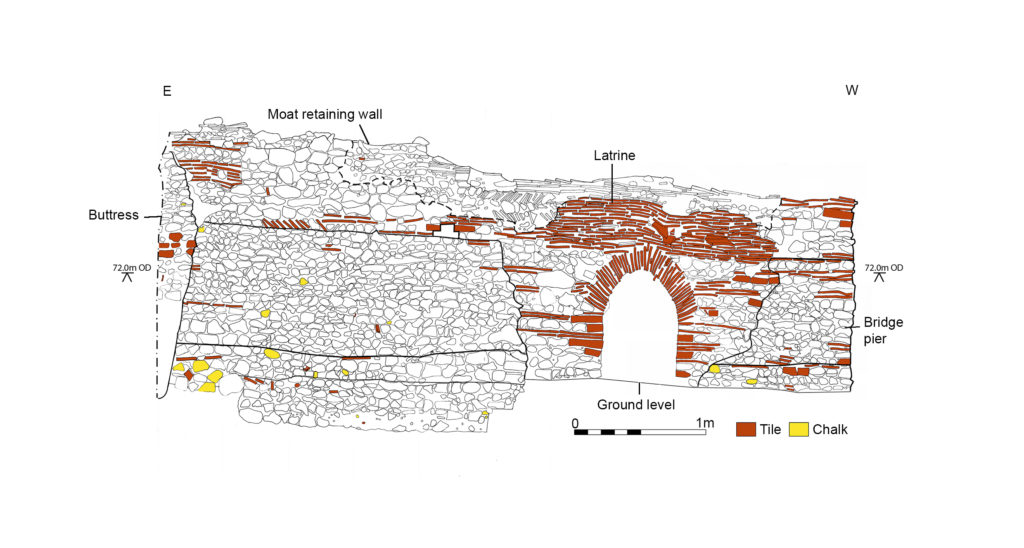

Picton, Pembrokshire: The aim of the project is to achieve a full understanding of the form, functions and affinities of the medieval part of Picton Castle through a building survey. It has an unusual plan with no close parallels within Great Britain, but shows some affinities with castles further afield including, possibly, Gascony in France

Snodhill, Herefordshire: Excavation to explore the early masonry defences and attempt to resolve the entrance arrangements and to do a geophysical survey of the Eastern Bailey

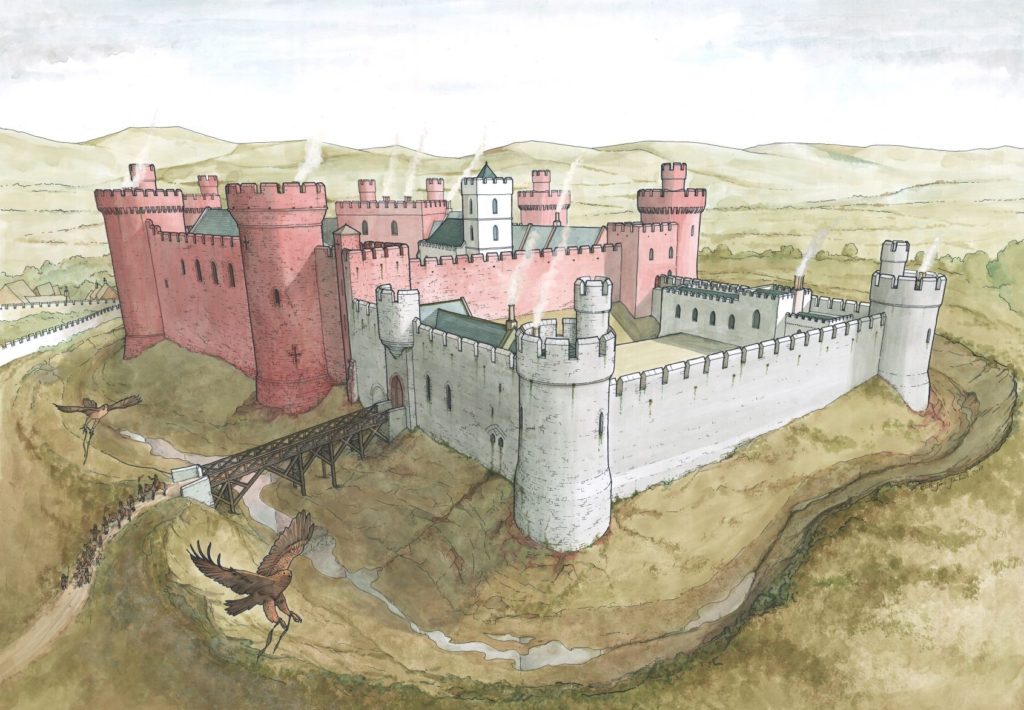

Wigmore, Herefordshire: To provide a digital reconstruction drawing of Wigmore Castle using a mixture of archaeological and archival evidence

We will not be able to fund as many of these projects as we would like. To help us fund as many of these projects as possible please donate here: Kindlink Donation Form App

The applications have been sent to our assessors who will go over them. You can see how the assessment process works from our blog back in January 2016: How the Castle Studies Trust Selects its Projects – Castle Studies Trust Blog