In the second half of 2024, Heneb’s Phil Poucher with the support and expert analysis of Neil Ludlow did the first ever detailed modern survey of the privately owned castle of Leybourne Castle, Kent, which has often intrigued castellologists as a key stepping stone in the development of gatehouses. Here Neil Ludlow explains what they found.

Leybourne Castle gatehouse was introduced to this blog last summer, just before the commencement of a programme of CST funded survey and research. The work is now complete, and really does show the value of in-depth studies like this: a somewhat different, and much more interesting picture has emerged. The Welsh Marches aspects of the gatehouse design had been noted, along with patterns of baronial influence including the close links between Leybourne’s lords and the Valence earls of Pembroke; a start-date between c.1300 and 1310 had also been mooted. However, certain key features revealed by detailed study of the gatehouse allow its dating and affinities to be refined more closely, while pointing fairly persuasively to a female builder.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

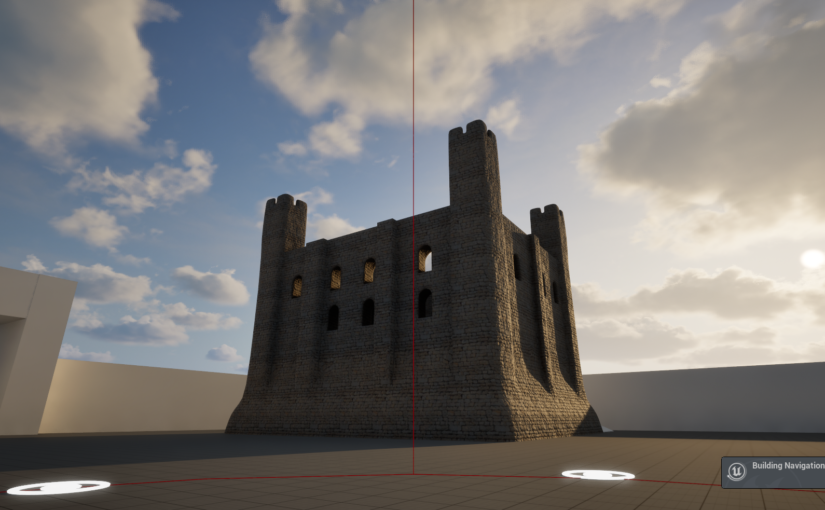

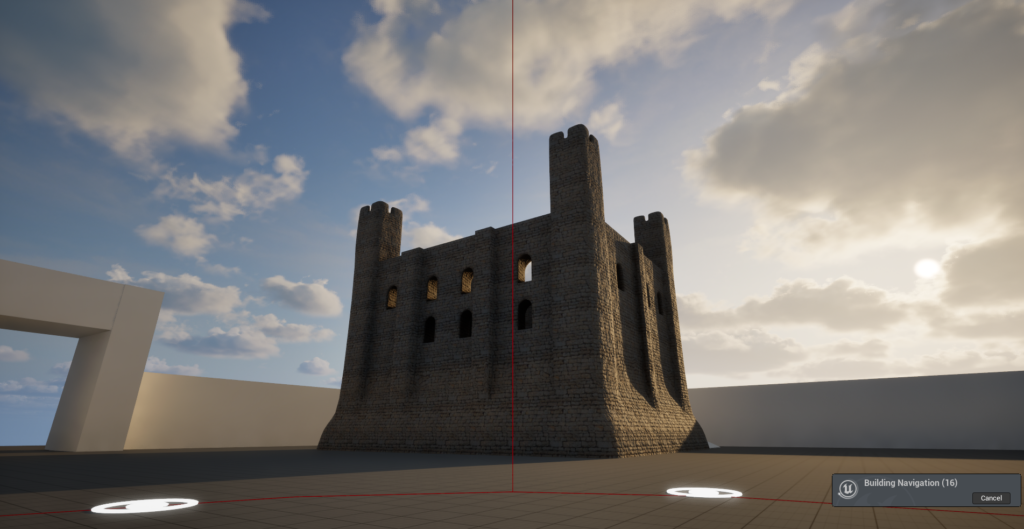

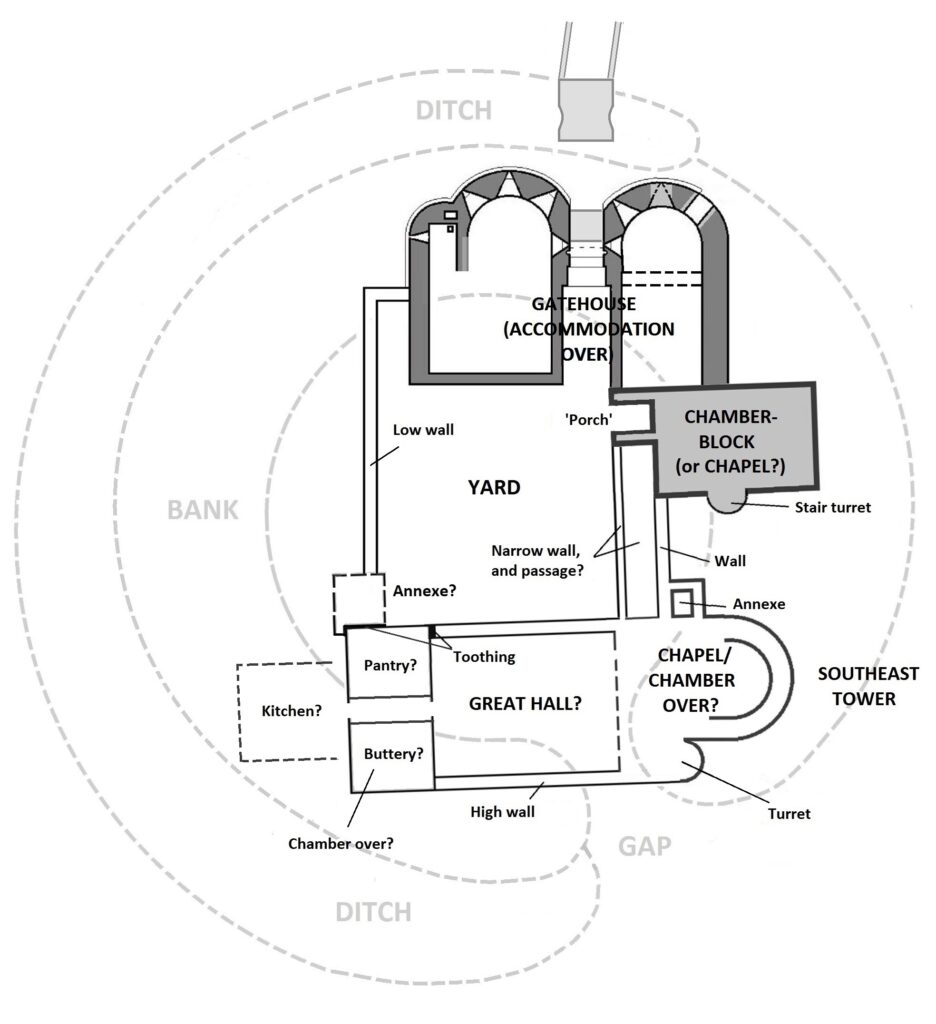

With origins as a ringwork castle, Leybourne was later ‘fortified’ in masonry, rather lightly, to become a rectangular courtyard house somewhat awkwardly superimposed upon the earlier earthwork. The masonry comprises a twin-towered gatehouse attached to a large, rectangular storeyed building – now gone – that may have been a chapel or, perhaps more likely, a chamber-block. The latter appears to have been connected by a passage to a third D-shaped tower at the southeast corner. This tower lies opposite a smaller, rectangular building at the southwest corner, that may represent a service-block and overlying chamber, with a Great Hall formerly lying east-west between them. The remaining side of the castle, to the west, was defined by a lowish wall.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Stylistic evidence suggests all the masonry at the castle belongs to one overall campaign, centering on the years 1305-25 and showing influence from the Welsh borderlands – probably via associations between the Leybourne lords and two Marcher families, the Valences and the Cliffords. The evidence for its dating and affinities is fairly precise, and can be summarised as follows –

- The gatehouse shows a high outer arch, a feature with origins in the Welsh Marches 1280-1300.

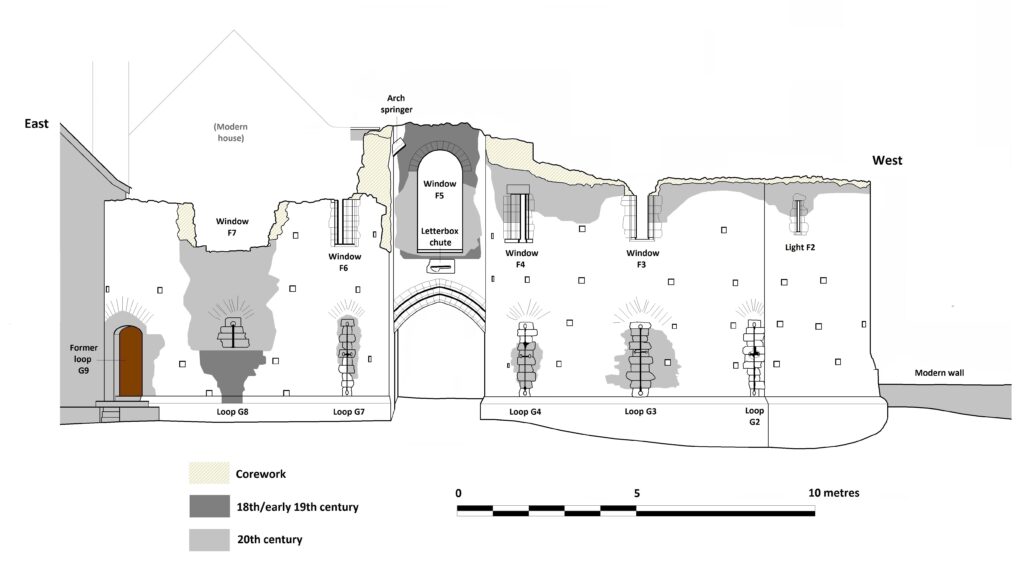

- It also shows fully-oilletted cruciform loops, which were similarly developed in the Welsh Marches 1280-1300 where they were extensively employed by the Clare lords of Glamorgan, and also by the Valences. One of the Leybourne loops survives unaltered, demonstrating that they are original features, though mostly now rebuilt or modified.

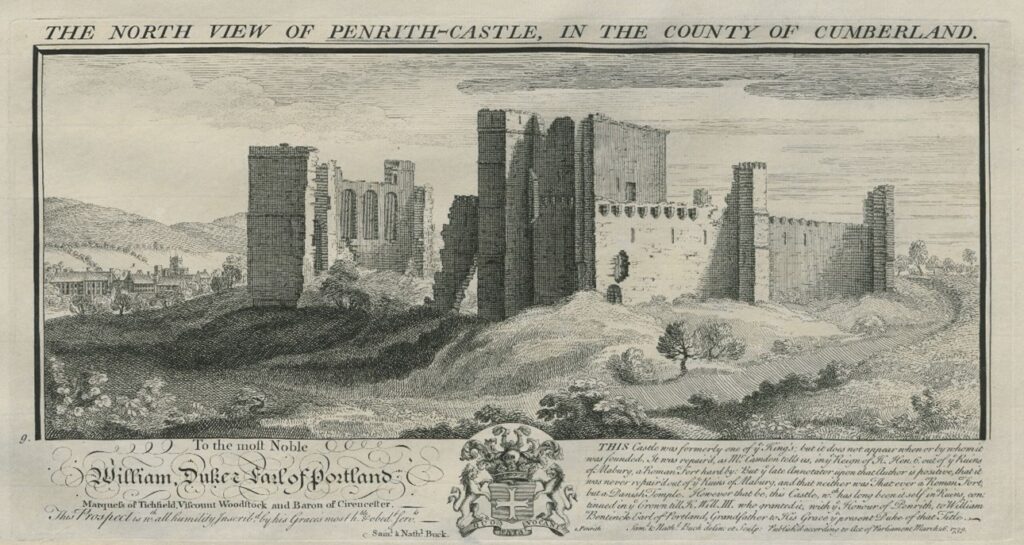

- The gate-passage lies beneath a quadripartite rib-vault, normally confined to the 1330s onwards but with an early example in the gatehouse built by Aymer de Valence, earl of Pembroke, at Bampton Castle, Oxon., in 1315-24.

- A ‘letterbox chute’ overlies the entry, as at Caerphilly Castle, Glam. (1270s) and Bampton Castle (1315-24).

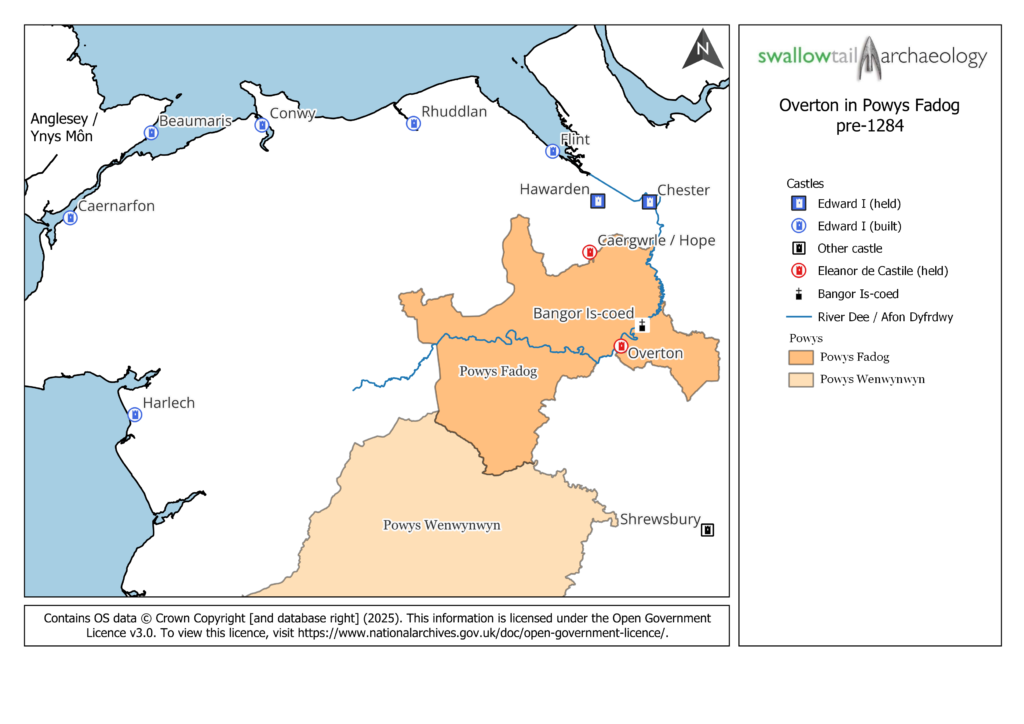

- The entry is deeply recessed between flanking towers, as in Edward I’s Welsh Castles at Rhuddlan, Harlech and Beaumaris (1270s-1300).

- The windows have double-chamfered rebated surrounds, in a Marches style and similar to windows built by the Valences (1280s-90s) and another Marcher lord, Robert de Clifford (1300-1314), eg. at Goodrich Castle (Herefs.) and Brough Castle (Westmorland).

- The Southeast Tower shows a doorway with a raised threshold (like a ship’s bulkhead door), as in work from 1300-1310 at Bothwell Castle, Lanarks., and Brougham Castle, Westmorland, by Aymer de Valence and Robert de Clifford respectively. Two more possible raised thresholds have been revealed at Leybourne in service trenches.

- The portcullis would have been fully-visible when raised, as at Chirk Castle, Denbighs., and Tonbridge Castle in Kent, which itself shows considerable Marches influence; both are probably from the 1290s.

- The portcullis grooves have ¾ round profiles as in the outer gate at at Corfe Castle (1280s), but their margins are refined with rounded chamfers.

- The gatehouse is flanked by a D-shaped latrine turret that may be influenced by a similar turret at the Clares’ Llangibby Castle, Mon. (1307-14), at least in function, if not in its precise form: unlike Llangibby, it lies parallel with the axis of the tower.

- It houses a fireplace with a rounded back, normally characteristic of earlier work but also seen in the Great Hall fireplaces at Pembroke Castle (William de Valence, 1270s) and Haverfordwest Castle, Pembs. (probably Aymer de Valence, 1308-15).

- Aspects of their design, detail and planning suggest the D-shaped Southeast Tower, the former ?chamber-block and the Southwest Building were all contemporary with the gatehouse.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

During the period 1305-25, Leybourne Castle appears to have been in the sole possession of a woman – Alice de Leybourne (née de Toeni). She received the castle and manor on the death of her husband Thomas de Leybourne in 1307, and all evidence suggests that she held it, in her own right, until her own death in 1324. She was the only beneficiary when her brother Robert died in 1310, providing the necessary resources. Under her tenure, Leybourne appears to have retained its status as the caput of an extensive Kentish lordship, and it is likely that the gatehouse represented accommodation, and administrative space, for its officials. Alice may therefore join the list, currently very short, of women castle-builders.

A number of other results have emerged from the present study. I suggest that a significant amount of work was undertaken by the Leybourne family at Leeds Castle, Kent, before it was acquired by Edward I’s queen Eleanor in c.1278, that this work included the creation of the lakes for which the site is celebrated, and that they may have been the inspiration for the lakes at Caerphilly Castle. It is also possible that the extensive work from c.1300 at Brough Castle, Westmorland, was undertaken by another woman – Alice’s aunt, Idonea de Leybourne.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

To see the full report please go here: Leybourne, Kent | Castle Studies Trust

Please note Leybourne Castle is privately owned and not open to the public.