Sara Cockerill, author of the recently published biography of Eleanor of Aquitaine, looks at her role in English castle development.

One of the areas which has stayed slightly “off-camera” as I have written about Eleanor is the question of her relationships with the castles of her era. The headlining castles built under Henry’s aegis show no signs of Eleanor’s input. More intriguing however, is her relationship with those castles which pre-dated Henry’s reign and which found themselves in need of a bit of TLC – not necessarily from a military point of view, but in order to function as homes as well as defences. Where this sort of work is concerned there seems to be some ground for tracing a link between Eleanor’s regencies and the initiation of refurbishment programmes.

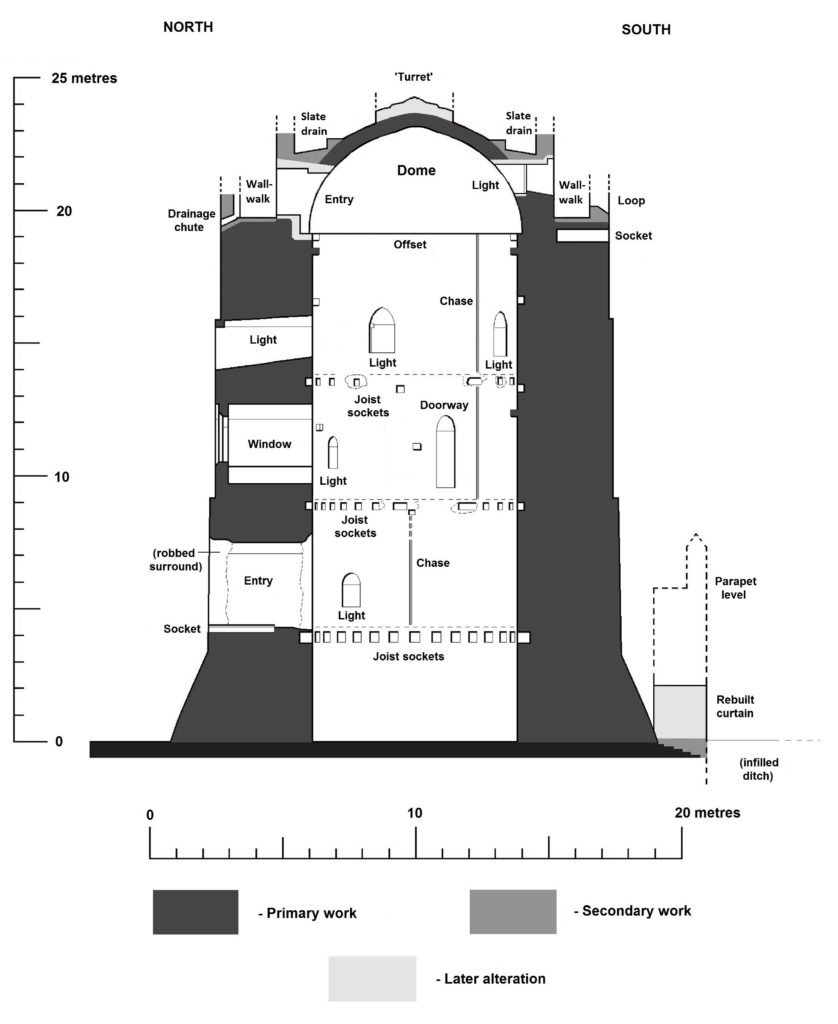

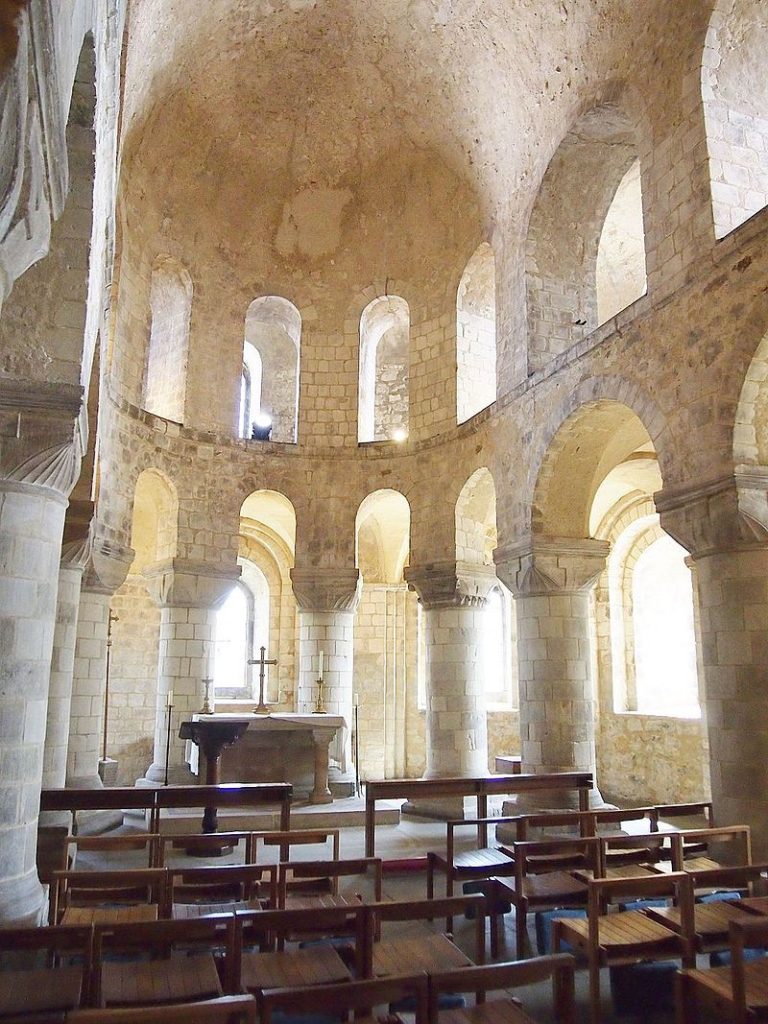

To start with the most obvious example – the Tower. On Eleanor’s first arrival in London the Tower was uninhabitable, and the royal couple had to stay instead at Bermondsey Abbey. While it is clear that Henry II put Thomas Becket in charge of refurbishing the equally run down Palace of Westminster, money does not commence to be spent on the Tower until 1166 – during Eleanor’s regency, suggesting that she had some hand in the decisions as to its refurbishment. Quite what these were is of course a matter of some debate, but they included as well as defensive works, quasi domestic features, such as work to the chapel and living accommodation.

Tower of London Chapel of St John, By Slowking4 – Own work, GFDL 1.2, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=34675029

Another castle which came under Eleanor’s review is Berkhamsted – initially given to, and refurbished by Becket, it was transferred to Eleanor, who held the barony as part of her dower assignment, during the course of Henry’s quarrel with Becket, with the royal family spending Christmas of 1163 there; an event which involved numerous items of plate being sent from Westminster to dress the rooms to best advantage. In the years which follow, again during Eleanor’s regency, there is regular work noted in the accounts, on the “Kings houses” there, at the granary, the bridges – and the lodgings. Her interest in the property is further evidenced by her travelling to stay there as soon as she gained a greater measure of freedom in 1184, with the advent of her daughter Matilda, then in exile from Saxony. Eleanor and Matilda’s family seem to have spent the whole summer there. And finally – work stops on the castle just at the period when Eleanor departs to her retirement in Poitou. However even in retirement her steward for the Berkhamsted estate would travel to visit her at Fontevraud….

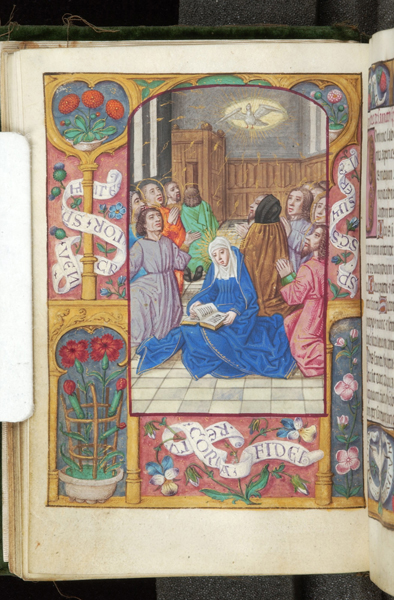

Other places where Eleanor was particularly at home and where her interest can be traced are Old Sarum (Salisbury) and Winchester – her main locations during her captivity. But everything suggests that she was sent there not because she disliked them, but rather the reverse. Both are places she positively chose to visit on more than one occasion as regent in the 1150s and 1160s. Winchester, of course, was Henry I’s main residence, and had benefitted from a constant programme of renewals ever since. Interestingly however its domestic architecture was thoroughly overhauled from the year after Eleanor arrived in England. In 1155–6 £14 10s. 8d. was paid for making the king’s house and the next year another £14 10s. was spent for work on just one chamber in the castle. In 1170 £36 6s. was paid, and in 1173 £56 13s. 1d. was paid for work on the king’s houses at Winchester and £48 5s. for work on the castle and provisioning it. Large sums of money were, interestingly paid for the King’s chapel, in the years when Eleanor was a frequent resident there in confinement. To this period too can be traced the first indications of development of the gardens. Old Sarum for its part had a residential area which was modern, having been built as recently as 1130 under the aegis of the then bishop. During Eleanor’s residence at Salisbury in the 1170s and early 1180s, there was consistent expenditure including £47 on the houses in the year Eleanor came to live there. That Eleanor positively liked Salisbury is shown by the fact that after her release she chose to organise the wedding of André de Chauvigny to the heiress Denise of Déols there; and Winchester too was a voluntary stop for her more then once in her later years.

In a similar category is Windsor castle. Though predominantly a project of Henry’s – the defensive remodelling smacks of his planning – Eleanor spent considerable periods of time here – bearing Matilda here when the castle must have been a building site, and visiting repeatedly both as regent when she may well have had a hand in the development of the domestic buildings, which were to form a family base for her descendant Henry III’s family. Again it is a castle she seems to have positively chosen to visit with Matilda on Matilda’s return, and again following her release.

Although of course Berkhamsted has fallen into disrepair, one can perhaps therefore trace Eleanor’s hand in creating a core of castles which could double as homes, which was to influence the lives of generations to come.

Featured image: Aerial photograph of Old Sarum site, on departure from Old Sarum airfield by Mark Edwards.