Project lead, Steve Parry, looks at what he and the team from MoLA and the Higham Ferrers Archaeology and Research Society hope to achieve during their geophysical survey of the once royal castle of Higham Ferrers starting on Monday 15 July 2024.

Walking through the streets of Higham Ferrers you’d be forgiven for thinking that you are looking at a pretty but provincial town. However, documentary records reveal that Higham Ferrers once played a role on the national stage. During the Middle Ages it had a substantial stone-built castle which served as the headquarters of the extensive Northamptonshire landholdings of the Duchy of Lancaster and from 1399, became a possession of the Crown. This castle, which was also the manor, would have been the focal point of the medieval town along with other fine nearby buildings including the Church of St Mary, the School House, the Bede House or hospital and the College founded by Henry Chichele, Archbishop of Canterbury before 1425. While these other buildings have survived to the present day the castle fell into disuse and was demolished in the early sixteenth century, with Henry VIII granting building materials from the site for the rebuilding of Kimbolton Castle. John Norden’s map of 1591 shows the site of the castle (‘b’) as broken masonry and uneven ground adjacent to the church, and all that now remains are a ruined dovecote, fishponds, and rabbit warren.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

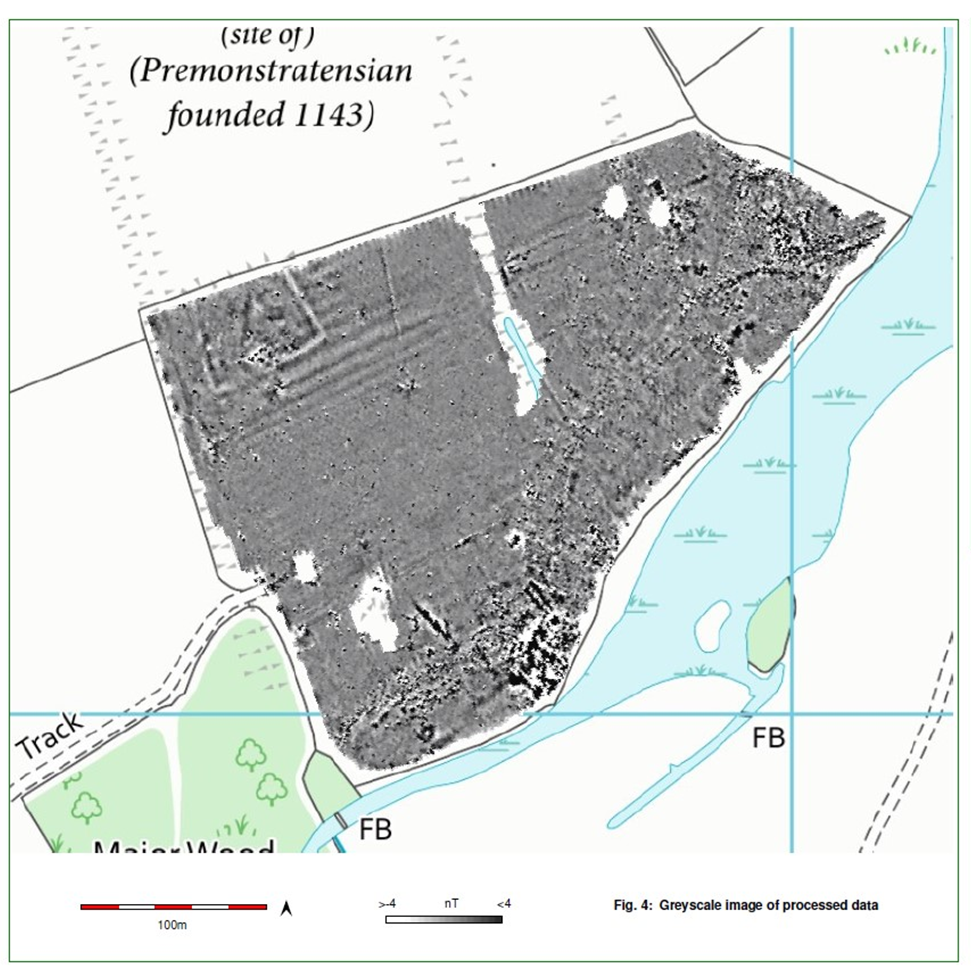

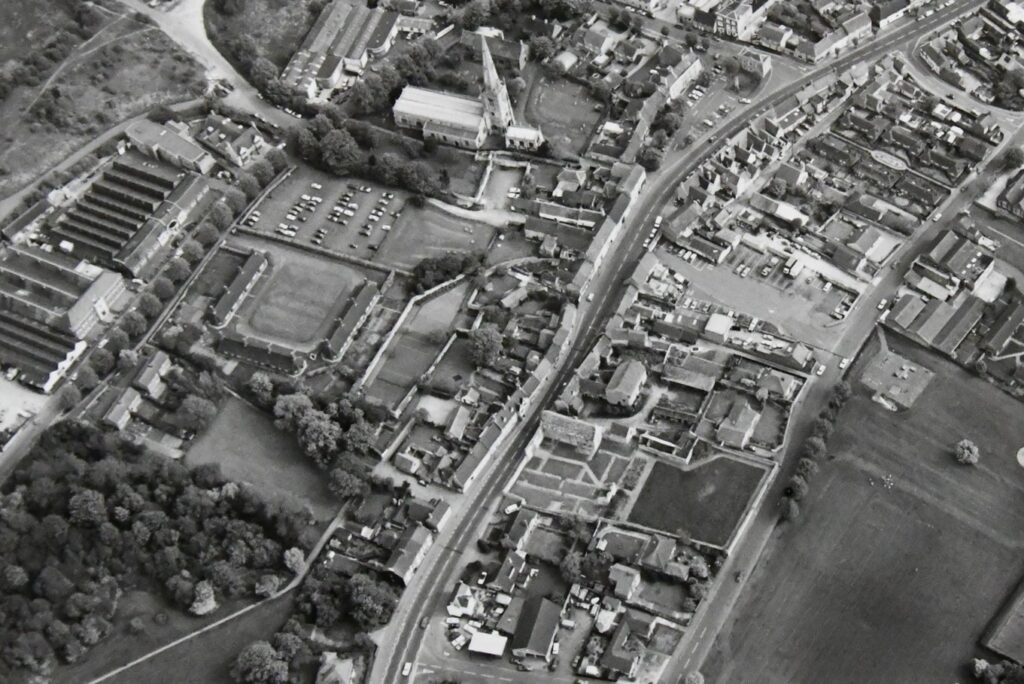

Thanks to a generous grant from the Castle Studies Trust, Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA), will work with Finham Heritage and members of the Higham Ferrers Archaeology and Research Society (HiFARS) to reveal Higham Ferrers’ royal connections through a series of geophysical surveys. We will use a magnetometer to identify any substantial ditches around the castle, as well as the buried remains of internal features such as robbed-out walls, hearths, and pits. Alongside this, the team will use ground penetrating radar to locate the principal buildings of the castle confirming (or denying!) what our documentary sources tell us – that this substantial medieval building included a hall, chapel, tower house, King’s and Queen’s Chambers, not forgetting three substantial gates. Finally, a resistivity survey will be undertaken, with the particular support of HiFARS members, to provide further detailed information on any buried wall foundations or other structural remains. The surveys will be undertaken in the various plots shown in this photograph from the 1980s extending from the church (top centre) to the small wood (bottom left-hand corner).

Reproduced by permission of Northamptonshire HER

Together with the documentary sources, the geophysical surveys will, we hope, shed light on the evolution of the site by:

- Seeking evidence of a late Saxon and early medieval manor pre-dating the construction of the castle.

- Testing the widespread assumption that a motte and bailey castle was built by William Peveril, who held the manor in 1086.

- Attempting to map the layout of the late medieval stone castle.

The findings of the surveys will be considered alongside those of limited excavations in 1992, to see how the castle and its associated buildings fit within the development of Higham Ferrers from a Saxon administrative centre to medieval market town. The results and conclusions will be shared via a public lecture and published as a report on the Castle Studies Trust website.