We often think of castles as formidable fortifications around which the medieval world pivoted. Fierce sieges were invested to capture key sites; the Keeper of the Tower of London was a prestigious role, and Dover Castle was the ‘key to the kingdom’.

But castles also had a domestic side. They were residences of the barons, earls, and monarchs who ruled in medieval society.[1] They were decorated with rich tapestries as seen at Chateau d’Angers in France, the scene of magnificent feasts, and wrapped up in symbolism. The Earl of Cornwall built a castle at Tintagel because the place was linked to Arthurian legend.

Personalities are intricately linked to the story of each castle, not always those who owned them. Thomas Percy built Wressle Castle in the 1390s. The Percy family was a powerful dynasty in northern England and Wressle was a fortress-palace within carefully constructed garden. Designed by John Lewyn, one of the leading architects of late 14th-century England, the castle had only recently been completed when the fortunes of the Percy family took a turn for the worse.

In 1403 Harry Hotspur, Thomas’ nephew, rebelled against King Henry IV with a string of grievances. Thomas joined the rebellion which was eventually defeated the battle of Shrewsbury. Thomas was captured and executed for his role and the Crown took control of Wressle Castle.

For nearly 70 years the castle either remained with the Crown of was temporarily given to favourites of the king. In 1471 it was finally returned to the Percys, with Henry Algernon Percy making his mark on the castle by updating the interior and the gardens. The gardens contained a two-storey building call the ‘School House’ with paintings of proverbs across the interior. This may have been where Henry Algernon Percy came for some quiet reading.

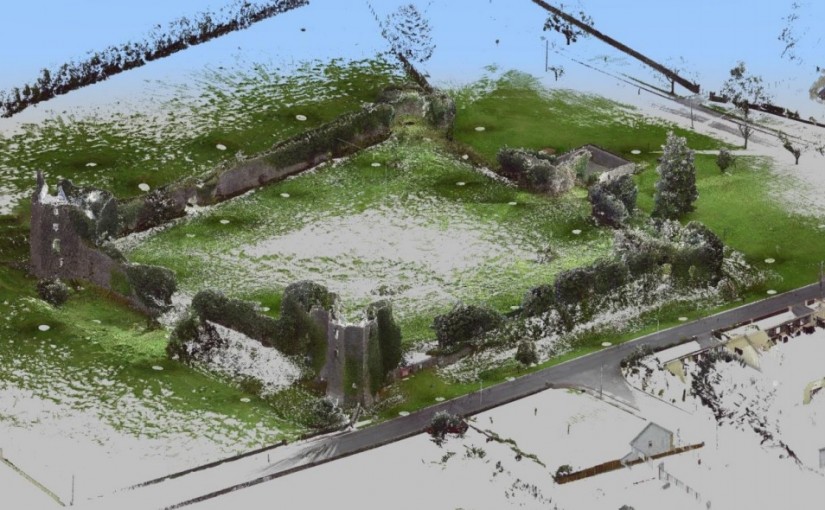

Wressle Castle never witnessed a siege, though it was garrisoned during the English Civil War in the 17th century. In fact the majority of castles never faced the attacks they were designed to withstand. Despite that the castle lies in ruins today. The garrison themselves left their mark, causing damage estimated at £1,000! After the war the castle was partly demolished, leaving just a quarter standing which can be seen today – though it is on private land. The following century the interior was stripped by fire when a tenant tried unsuccessfully to clear a blocked chimney.

Wressle has a rich history which the survey we funded in 2014 and carried out by Ed Dennison Archaeological Services shed further light on. When Thomas Percy decided he wanted a castle in the late 14th century the village of Wressle lay in the way. The settlement used to extend further to the west, but was pulled down to make way for the castle gardens.

Castles have a direct impact on local communities, and those castles are shaped by the personalities that live in them, who drag them into disputes, and who occasionally fail to unblock chimneys. Next time you’re at a castle take a moment to learn about the people who shaped the building you’re standing in and think what it must have been like.

Want to know more about Wressle or our other projects? Watch our video about the landscape survey or sign up to our newsletter.

[1] Catriona Cooper at the University of Southampton used digital media to explore the experience of living inside a medieval castle, looking at Bodiam and Ingtham Mote.