Summers for me always mean getting together with friends and family for BBQs and picnics. The simple act of hosting a party comes with a range of logistics for the host to manage: buying, cooking, and serving food, providing entertainment, ensuring everyone is enjoying themselves, along with more practical tasks such as cleaning communal areas that guests will frequent. The Tudor period did not entail many modern-style BBQs in the backyard; however, hosting celebrations was a large part of elite culture. Scholars of hospitality in the medieval and early modern periods have long recognized its social and cultural significance. Generosity was a Christian value and was expected from those who could afford to provide it.

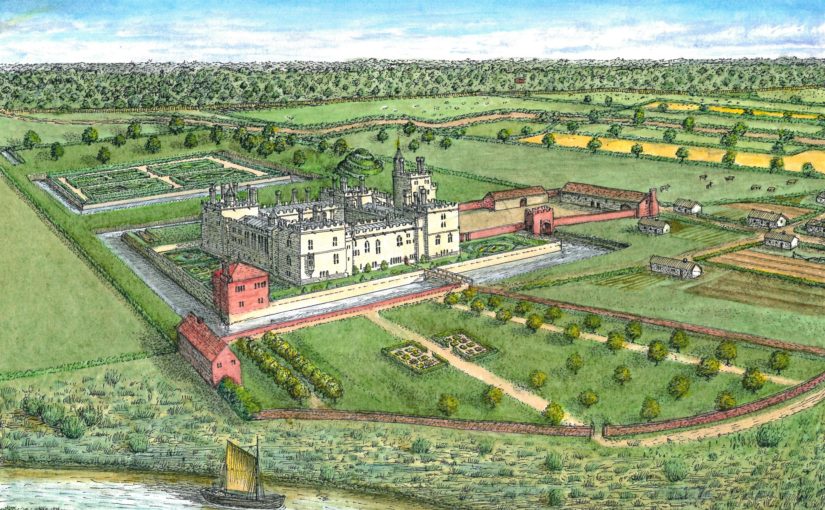

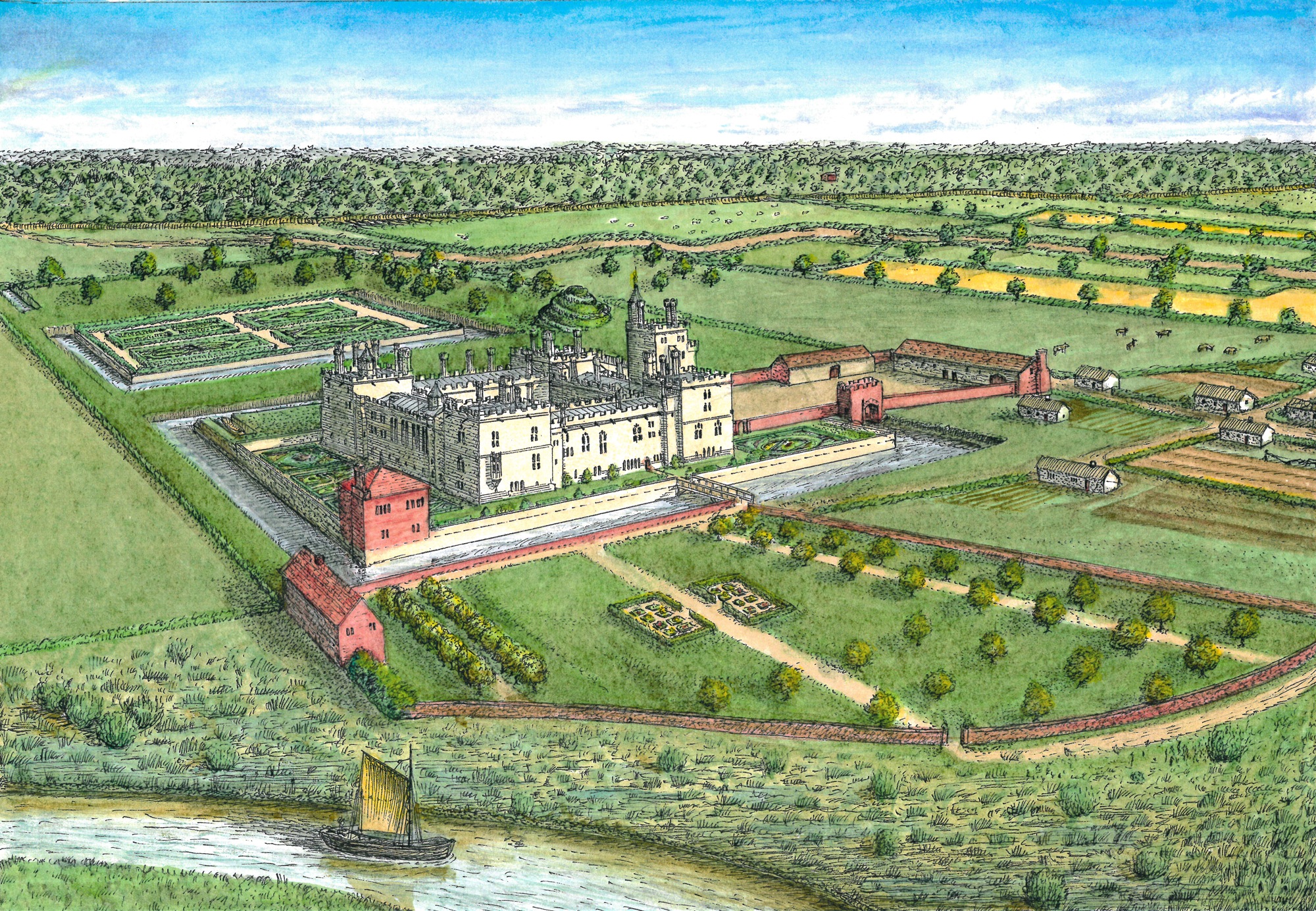

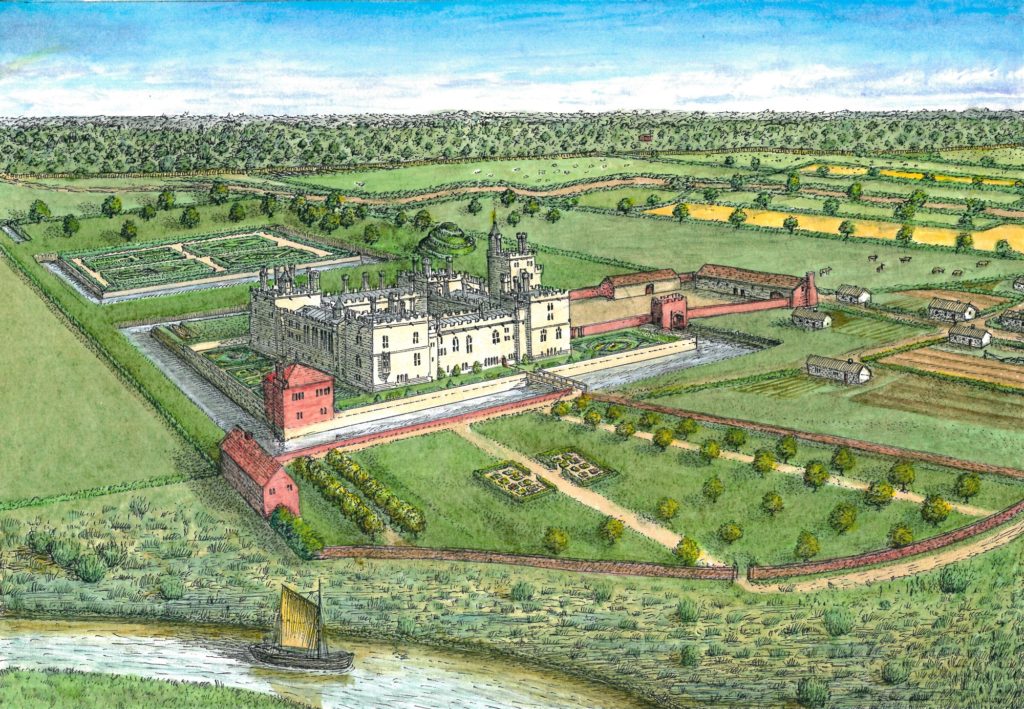

Hospitality leaves very little trace in architectural remains, so historians must turn to documentary records to investigate how castles were used to host feasts and celebrations. Household Books are one such record that provide a clue into the extravagance and hierarchy of these revels. These documents were created as a sort of ‘how-to-guide’ for management and maintenance of a large residence. Unsurprisingly, households played a main role in the performance of hospitality and therefore, protocols for dining and hosting are a common feature in these records. King Edward IV’s Liber Niger is one of the most used sources for demonstrating the splendour of royal households, and many of the large noble households of the late medieval period take some instruction from the king. For instance, Henry Percy, the fifth earl of Northumberland (1477–1527) kept a detailed Household Book for the year 1512 in which daily ritual and splendour are of the foremost concerns.[1] The Northumberland Household Book (NHB)is specifically for the earl’s main castles of Wressle and Leckonfield in Yorkshire.[2] It gives exact numbers of servants, their role and responsibilities, instructions for dining etiquette, and seeing to the lord and his family. In a theoretical sense, it provides us with an image of the perfectly run noble household.

One of the concerns in the NHB is the procedure for eating. It tells us that the earl of Northumberland sat at the high table with his wife, Catherine Spencer, and his son and heir, Henry Percy. Northumberland’s other two sons, Thomas and William, served the food for the high table.[3] The NHB continues to list a total of sixteen people to attend the needs of the lord and his family, including ‘the childe of the kechinge that shall help the saide Yoman or Groome to dresse my Lords Metes and Servyce for the Howsehold And to be ath the Revercion’.[4] After the list of those serving the high table, the NHB lists the people who should sit at each of the tables in the great chamber and subsequently in the great hall. Controlling where people sat, the food that they ate, and the order of service was one way for a lord to visually display and reinforce the social hierarchy on a daily basis.

Some days called for special feasts and the NHB isolates the principal feasts of the year when the household could expect a ‘great repaire of Straungers’ arriving at the castle. These days include: Easter, St George’s Day, Whitsun, All Hallows Eve, and Christmas. These celebrations did not just provide food for guests, but entertainment as well. For the Twelfth Night celebrations at Wressle in 1512, the ‘hoole chappell’ was directed to ‘sing wassaill’, a carol celebrating the service of the wassail drink at the evening banquet.[5] On All Souls Day, Northumberland’s chapel performed the ‘responde callede Exaudivi at the Matyns-tyme for xij virgyns’.[6]

In an earlier blog post for the CST, Dr Kate Buchanan explored ideas of a social gathering around Christmas time at Huntly Castle and the sensory experience that those present might have experienced. She demonstrates that hosts could – and oftentimes did – blend business with pleasure when it came to hospitality. This is definitely the picture from other fifteenth- and sixteenth-century household books. Celebratory periods brought family, peers, political allies, and even tenants together under one roof. Castles facilitated the gathering of a community and it was the space in which relationships could be forged.

Hospitality was just one way that castles were used to promote and uphold the social hierarchy of Tudor England. We must remember that hospitality was not just an act that the host actively placed on the passive guest. It was very much a performance with the household servants as many of the main players. Servants prepared and served the food, attended to guests, and ensured that everyone adhered to protocol. Castles played a much greater role than being the theatres on which this performance took place. The great hall and the household chapel were key areas in the castle that hospitality was dispensed. These spaces brought everyone in the castle together for entertainment and allowed for interaction of people across the social and gender hierarchy. These interactions were of course heavily regulated. Although castles accommodated people from across the social spectrum, they helped to ensure, through visual cues, the social order of premodern England by promoting the owner’s wealth and status through ritual and display.

If you would like to know more my forthcoming book, The Culture of Castles in Tudor England and Wales will be available in September 2019 from Boydell Press.

[1] Henry Algernon Percy, The Regulations and Establishment of the Household of Henry Algernon Percy, the fifth Earl of Northumberland at his Castles of Wressle and Leakenfield in Yorkshire (London, 1905).

[2] The Castle Studies Trust has funded two projects at Wressle. You can explore the findings here: http://www.castlestudiestrust.org/Wressle-Castle.html

[3] The Regulations of the Earl of Northumberland,pp. 349-353.

[4] The Regulations of the Earl of Northumberland, p. 351.

[5] The Regulations of the Earl of Northumberland, pp. 342-3.

[6] The Regulations of the Earl of Northumberland, pp. 342-3.

![[10] Druminnor Castle - "Woops!"](https://farm6.staticflickr.com/5125/5340893447_176baa5abf_b.jpg)