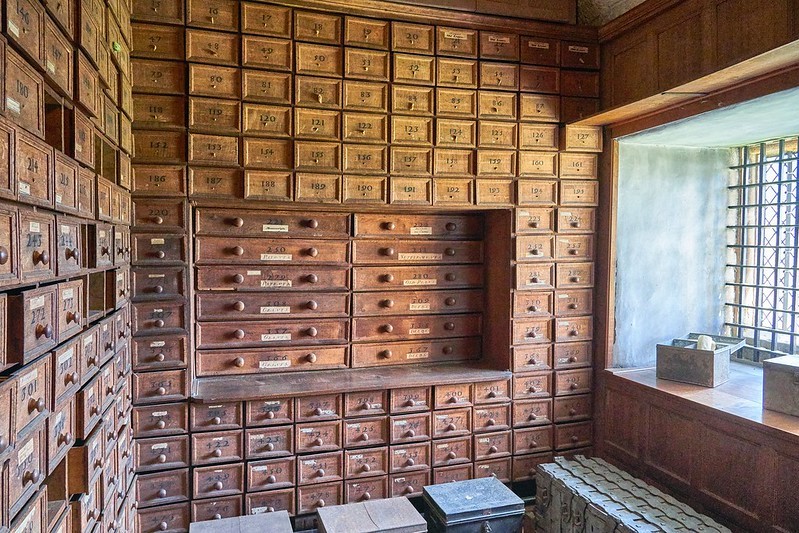

Anyone interested in the study of the past knows the importance of records and documents for information gathering. Records and proper documentation are not just important for historians, but they played a central role in the everyday management of a medieval and early modern landowner too. Creating and maintaining accurate records was only half the battle. They needed to be kept safe and easily accessible for the landlord or estate managers. By the sixteenth century, most documentation was being stored in muniments chambers in elite residences. Royal castles and residences had muniments chambers for centuries and it started to permeate into the nobility and gentry as they began needing their own documentation close at hand. Below is an image from Hardwick Hall of the muniments chamber of Bess of Hardwick. Spaces could be large and purpose-built, like the chamber below, or a series of chests that could be locked.

By the late sixteenth century, muniments chambers were a necessity in any high-status house. The nature of these spaces is conveyed by Richard Braithwait’s (1588-1673) prescriptions that an earl ‘have in his house a chamber very stronge and close, the walls should be of stone or bricke, the dore should be overplated with iron, the better to defend it from danger of fire’.[1] For Braithwait, the bulk of documentation related to landownership demonstrating the connection between documents and lordship. The documents needed to be kept orderly with ‘drawing boxes, shelves, and standards…and upon every drawing box is to be written the name of the Mannor or Lordship, the Evidence whereof that box doth containe’.[2] His advice continues to help with the ease of retrieving the documents:

and looke what Letters, Patents, Charters, Deeds, Feofements, or others writings, or Fines, are in every box; a paper role is to be made in the saide box, wherin is to be sett downe every severall deede or writing, that when the Earle, or any for him, hath occasion to make search for any Evidence or writing, he may see by that Role, whether the same be in that box or not.[3]

The level of organisational procedure that Braithwait discussed concerning muniments rooms is a clear indication to their increasing use by the end of the sixteenth century. Moreover, the space itself needed to be practical and secure.

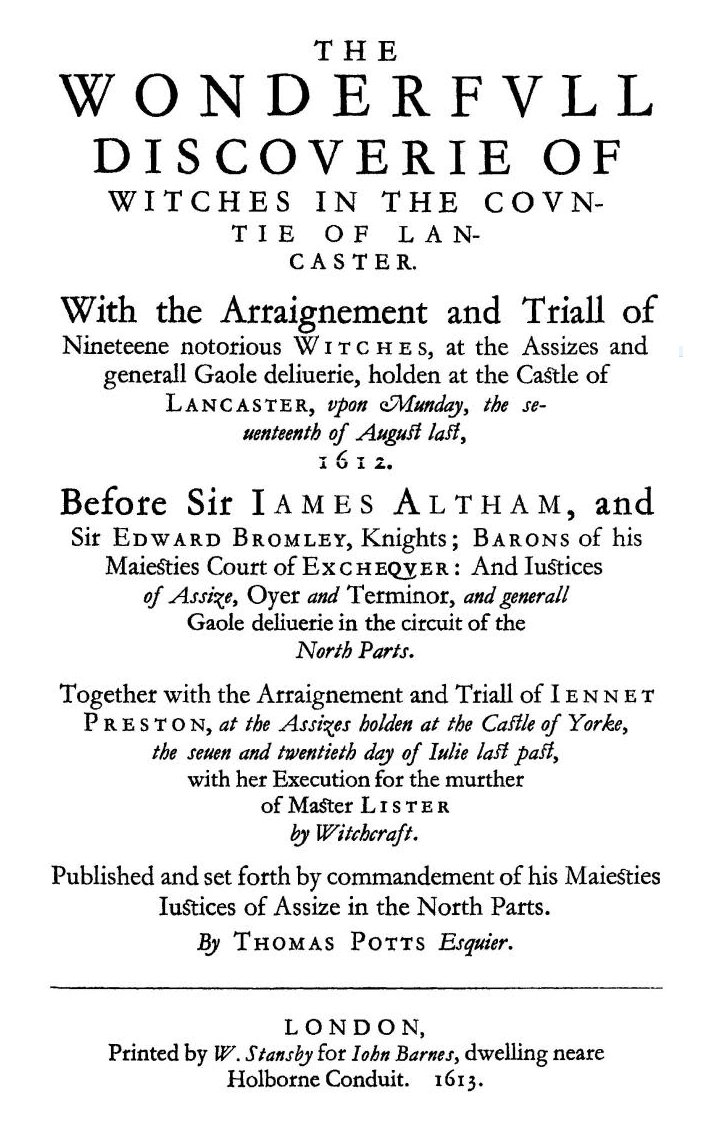

Do we actually have any evidence that Braithwait’s description is accurate or was this a pipe dream? Nearly a century before Braithwait’s publication we have evidence of a well-organised muniments chamber at Thornbury Castle, Gloucestershire used to store the documentation of Edward Stafford, third duke of Buckingham (1478-1521). Buckingham’s son, Henry Lord Stafford, transcribed a list of manuscripts that were in the duke’s possession shortly before the duke’s execution (British Library, Add. MS 36542). The list describes the contents of six large chests. The chests bore alphabetical lettering on them, and Carole Rawcliffe has suggested that the duke had developed a simple, but effective organisational system for his documents. Each of the six chests recorded in Lord Stafford’s list was bound in iron with plate locks, padlocks, and strong iron bolts. Estate papers and records related to specific farms and manors were boxed together on a topographical basis, county by county, with a description of the contents of the box. Lord Stafford’s desire for the storage and organisation of the documents related to Stafford land was primarily for his attempted recovery of the lands confiscated by Henry VIII upon the execution of his father. Nonetheless, there was a methodical system that was in place for the Buckingham archive well before the duke’s execution in 1521. Knowledge of the system in place would have made for an easy retrieval of the record needed just as Braithwait advocated a century later. It also indicates that many of these records were created for multiple future uses: for legal purposes, financial purposes, personal use, and even royal use. It was essential that they could be retrieved, presented, and read if needed.

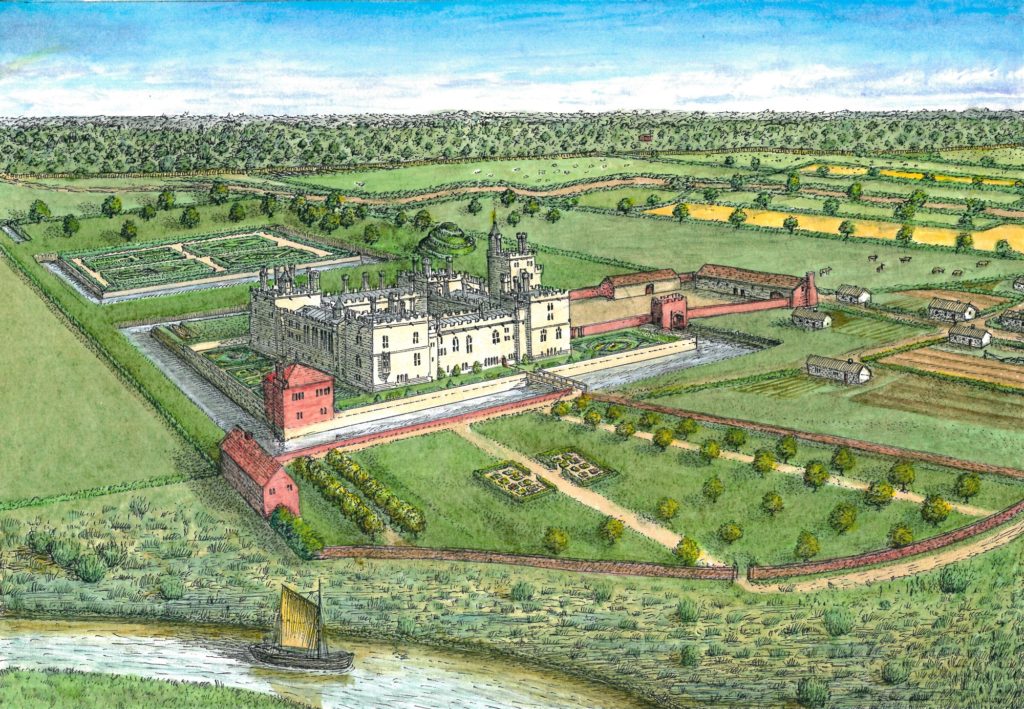

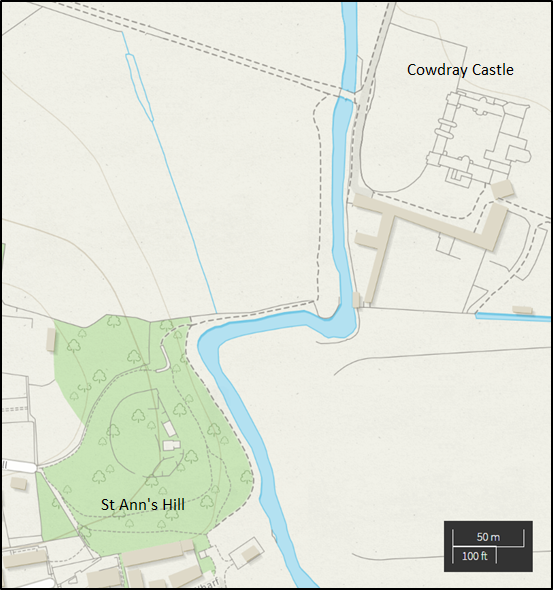

Organisation was of course key, but the storage space needed to be secure as well. Storing the hundreds, perhaps thousands, of documents that were created by and for the Staffords meant that the space accommodating them needed to be substantial, controllable, and close at hand. This space is an essential part of the materiality of this corpus of these objects. Thornbury Castle in Gloucestershire was one of Buckingham’s primary residences. The south-western tower of the inner courtyard married the range accommodating the elite apartments of the duke and duchess to the range containing the steward’s apartments and the gatehouse. On the second and third floors of this tower was the muniments storage chambers. The uppermost was described in a later survey as the place where ‘evidents’ were kept.[1]

The top chambers were considered the safest places to keep important records. The close proximity of the muniment chamber to the duke’s and duchess’s bedchambers spatially recognises the importance of their safe keeping as well as their private nature. Not everyone had access to the south-west tower at Thornbury: it was theoretically controlled through its proximity to the high-status apartments. Placing the muniments chamber so close to the elite apartments and the steward’s bedchamber kept the documents under tight security, but also it linked the documents to the people most likely to use them. The space was hidden away from prying eyes and on a practical level from the potential of a kitchen fire and an easy walk from the elite apartments to the muniments chamber.

Today we think of archives as cultural – and public – statements about the past; however, the muniments chamber at Thornbury was deeply personal and individualistic in nature. Indeed, the records within the chamber were oftentimes personal with the names of tenants, the amount of rent owed, and their geographical location; it was essentially their personal data. The chamber became a space that held a living memory of the duke’s tenant base. For Buckingham, the muniments chamber was spatial soul of his lordship. It was a physical manifestation of his power; written down and recorded for posterity. For his tenants, however, the muniments chamber represented their powerlessness and the one-sidedness of early modern lordship. The documents are written testimony to the exploitation of Buckingham’s lordship. His tenants had no control over their information and the storage of it. Although the muniments chamber at Thornbury might be thought of as a shrine to Buckingham’s lordly power, it contained documents that were not static. They held the names and rents of the duke’s tenants, payments to household staff, and the buying and selling of resources all of which were changing. Although muniments chambers are an often neglected part of our understanding of castle space, they held records related to the wider network of power and wealth that the castle is meant to symbolise.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

[1] Richard Braithwait, Some Rules and Orders for the Government of the House of an Earl set down by Richard Braithwait (London, 1821), p. 18.

[2] Braithwait, Some Rules and Orders, p. 18.

[3] Braithwait, Some Rules and Orders, p. 18.

[4] See A. Pugin, Examples of Gothic Architecture, 5 vols (London, 1831-8), II, p. 32.

[This is part of a much longer article about the Buckingham archive as an object that will appear in the Welsh History Review volume 30 number 2 in December 2020.]