In 2022 the Castle Studies Trust (CST) funded a 3-D digital scan of Raby Castle, County Durham, which was used as a basis for Richard Annis, then of Archaeological Services Durham University, to do a full building survey. Jeremy Cunnington, Chair of Trustees for the CST, takes a look at what he found, focusing on the medieval development of this complicated building that has seen many changes over the centuries, but retains most of its medieval exterior.

Like most castles built and owned by the aristocracy there is no written evidence of what was built when: clues lie in architectural and design features. While exact dates cannot be given, a phasing of what order structures were built in can be shown, much of which agrees with previous scholarship on the castle which suggests that much of the building took place between 1350-88 by the Lords of Raby, Ralph and his son John Neville.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

A licence to crenellate was granted in 1378 when a lot of the buildings were already in place, as the licence indicates when it refers to “towers, houses and walls”.

The origins of the castle are obscure. The property was obviously substantial enough to be stocked with deer from the royal forest in the mid thirteenth century, suggesting originally an unfortified manor house. Anthony Emery describes Raby as “an awkward and inconvenient shape [that] can only have been determined by an earlier residence on the same low and ill-defended site”.

Raby’s principal purpose has always been residential rather than military with comfortable living taking precedence over defence. The early building seems to be a standard hall house design, with the hall running north to south and utilities and household staff quarters at the north and the lord’s quarters at the south end.

Phase One of the Works

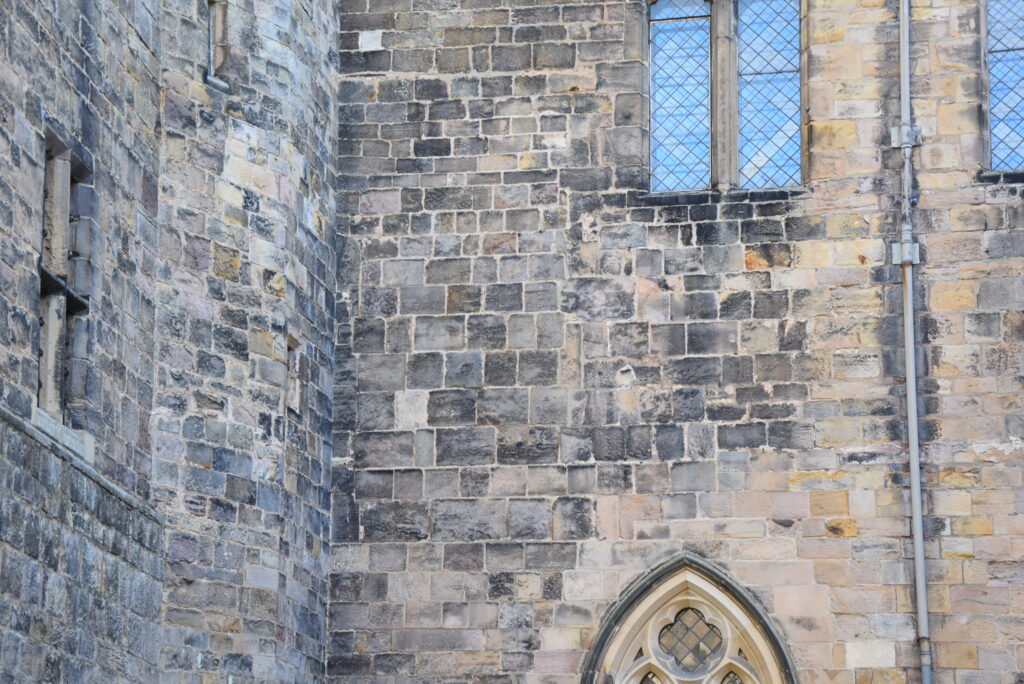

The earliest surviving part of the castle is the Great Hall block. The main discussion relates to whether it was built in two phases or one, with the ground floor being built in the first half of the fourteenth century, and being added to later in the fourteenth century, as proposed by Malcolm Hislop, or was all one build, proposed by Anthony Emery. Evidence for the former is based on the window tracery on the ground floor which is said to date from before 1320.

Regardless, the main entrance from the courtyard into the Great Hall block from the courtyard was always on the ground floor in a similar position to the current one. The blocked doorway on the first floor was a much later insertion to access an eighteenth century classical loggia. There was no evidence of a staircase down and more importantly the door does not align with the floor of the original first floor hall. Based on an old nineteenth century plan, the entrance to the first floor hall seems to have been a newel (spiral) staircase where the current chapel staircase is now.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Whenever the first floor was added, it was also when the majority of structures on the east side of the castle were built. Both the “Keep” and Mount Raskelf towers at the north end seem to have been built at the same time as the first floor of the great hall given the connecting passage from the first floor great hall to the Keep Tower and probably Mount Raskelf. Although not clear today with the re-arrangement in-fill of Mount Raskelf, both were of mirrored L-shaped design.

The first kitchen was on the ground floor of Mount Raskelf tower. It is also here where there are indications (heavy ribbed vaulting and the plain doorway) that the ground floor of the tower could have been built earlier, but the report found no evidence of a building break.

Equally it looks as though the chapel tower was built at the same time as the upper Great Hall, as it seems that the chapel’s west window, with no evidence of glazing, was intended to allow people in the upper hall to observe, or, given the height of the window above the floor, to listen to services.

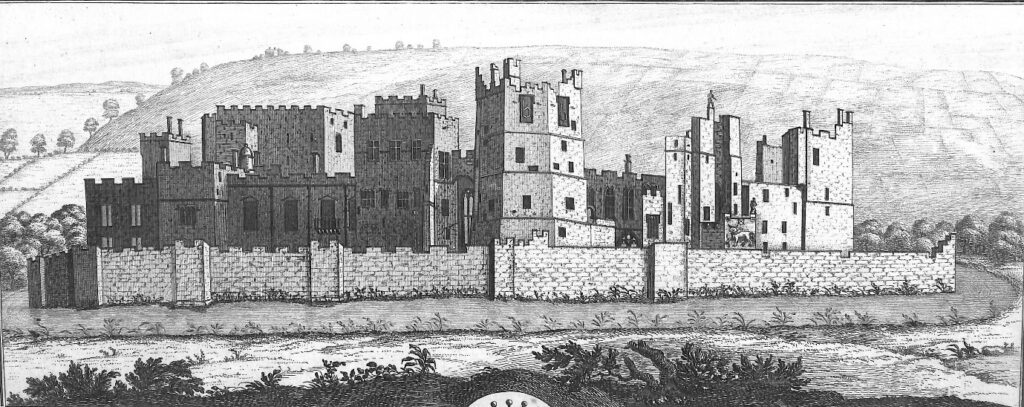

At the high status (south) end of the hall the accommodation differs from what it was like originally due to the destruction of the chamber block in the eighteenth century. The Buck engraving shows a square great chamber block which was connected to the moated en bec Bulmer Tower with an arched passage way at second floor level. It seems that it was for semi-private rooms for important guests while the Bulmer Tower was the lords’ truly private accommodation, which, in addition to the second floor link, had its own external stair and gate to the south terrace.

It also seems that the Bulmer Tower could date from the same time as the Mount Raskelf tower, as its basement, had the same vaulting as the northern tower according to Hodgson’s 1885 survey. Although no evidence of that now survives.

To the west of the Great Chamber block is Joan’s Tower which had two building phases. Its interior has been much re-arranged so there are no clues to its phasing but it is likely to have been at a similar time to the large expansion around the hall. The older part of the tower was square and had two floors.

Between the original Mount Raskelf and Chapel Towers may also have been the site of an old postern gate at the southern end of the Tower. Although now part of Mount Raskelf Tower the report also suggests that it wasn’t originally, based on later plans, the room in front of the putative gate was originally part of the gate passage and separate from Mount Raskelf . The elongated nature of the gate is also reminiscent of gates at the John Lewyn-designed Bolton Castle.

At some point this gate was blocked up and replaced by an entrance in the Chapel Tower.

Phase Two of the Works

Much of this work took place before the building of the famous Kitchen Tower which couldn’t have been before 1373. The survey shows that the Kitchen Tower was added after the addition of the two northern towers, given that the original kitchens were in the base of Mount Raskelf Tower, and the position of the kitchen which is slightly oblique to the axis of the hall range and northern towers and off centre between those towers. Richard Annis suggests that this is due to the owners wanting to have a service entrance at the south-east corner of the Kitchen Tower but still allow the kitchen’s dimensions to be similar to the kitchen at Durham Cathedral which was completed in 1372.

More works took place in the western part of the castle. This was probably when the castle took its current concentric form between 1381-88: the coat of arms on that extension shows the crest of John Neville who died in 1388 and Elizabeth Latimer who he married in 1381. The report assumes the Joan Tower extension, the building of Clifford’s Tower along with the (re) building of the Watch Tower and Western Range took place at this time, as they both extend beyond the original gatehouse to offer protection to the gatehouse or, just as likely, be an aesthetic way to create more space.

All these buildings have been greatly re-arranged but of them Clifford’s Tower is perhaps the most interesting, given that it was extra lodgings for high status guests. Originally, there was no way to access floors one to three from the ground floor. The only possible access to the first floor was from the West Range, but any evidence has been destroyed by later reworkings. Access to the higher floors seems to have only been possible from the first floor via a spiral stair in the south-east corner of the tower: remains of it were discovered during the survey. No other evidence survives of any other access. There might have been a service entrance from the north yard by a newel staircase and a putative mural passage in the small rooms but that is not certain.

That the (re) building of the Watch Tower dates to a similar period to Clifford’s Tower is based on the design of the two medieval windows in the east wall of the tower, which are paired lights with trefoiled heads identical to the surviving old windows in Clifford’s Tower.

Dating the building periods

It seems likely that, given that so many of the buildings were built simultaneously, which would require large resources, much of the building was carried out by John rather than his father Ralph. While the wealth and importance of the Nevilles of Raby was growing under Ralph thanks to a good marriage and royal service, it was under John that the family’s fortunes really took off. This was particularly thanks to royal service, especially in France from the 1350s onwards. This would have brought great rewards and also allowed him to be influenced by continental styles such as the en bec design of the Bulmer’s Tower. In the early 1370s following the unsuccessful expedition to Brittany he was rich enough to pay ransoms totalling £4,500 for some of his captured companions. It is also likely that it is after that time, when he was back in the north of England, and again from the late 1380s, after a brief stint in Gascony that he would have had the time to devote to the development of the castle and help turn it into the striking castle we see today.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Feature image courtesy of Daniel Casson

Bibliography:

Emery, A, 1996. Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300-1500 1: Northern England. Cambridge University Press

Hislop, M, 1992. The Castle of Ralph Fourth Baron Neville at Raby. Archaeologia Aeliana 5th series XX, 91-98.

—– 2007. John Lewyn of Durham: a Medieval Mason in Practice. British Archaeological Reports British Series 438. Oxford: BAR Publishing.

Hodgson, J, 1885. Raby in Three Chapters. Trans. Archit. & Archaeol. Soc. of Durham & Northumberland III, 1880-85, 113-127.

—– 1887. Raby. J. British Archaeological Assoc. 43, 307-27.

—– 1895. Raby in Three Chapters. Trans. Archit. & Archaeol. Soc. of Durham & Northumberland IV, 1890-95, 49-122