Canterbury Christ Church University was thrilled to receive funding from the Castle Studies Trust for a nine-month project that will produce a new digital reconstruction of Canterbury Castle’s Norman keep in the first century of its construction. The project’s ambition is to then use this new digital asset to create a pop-up exhibition and develop a curriculum resource for schools.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Canterbury Castle is one of 104 national examples of a tower keep castles (Scheduled Monument Number 1005194 (link)), and one of 20 Norman Castles built in Kent. It is part of a series of royal castles on the route from Dover to London and identified as being one of the earlier examples of the period, usually dated to between 1085-1125, with archaeological evidence suggesting a date c.1100-1125. It has been comparatively overlooked in the research of royal castles of the area, and the role that the castle has played in shaping the city has been overshadowed by other historic monuments, namely Canterbury Cathedral.

Screenshot of whitebox interior of Norman keep (courtesy of Mike Farrant)

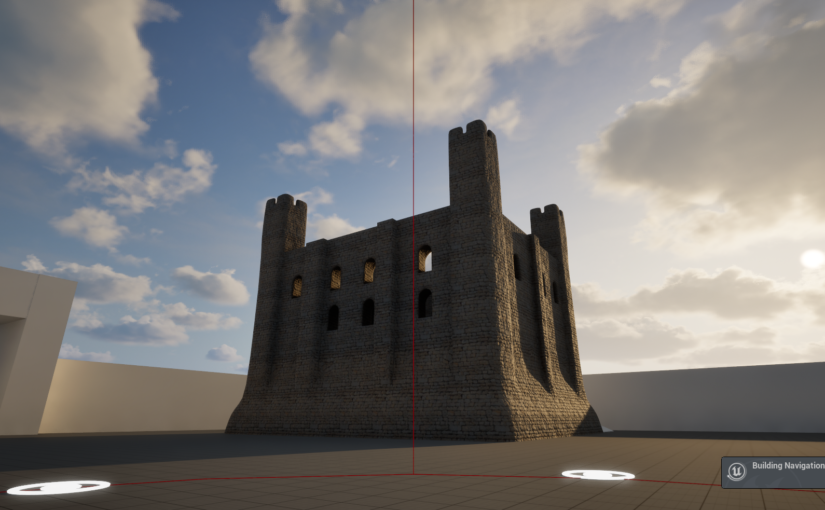

The digital model is being made in Unreal Engine 5, a games engine that enables the development of detailed and immersive digital environments, and draws on existing excavation data. Using a games engine to create the reconstruction facilitates an enhanced user experience; people will be able to walk around the keep’s grounds, and up through the floors of the castle giving them an enhanced sense of place and scale. Additionally, environmental conditions can be included to simulate seasons, weather patterns and even the night time constellations that would have been visible on a given date in the 12th century.

Visualising Canterbury Castle aims to interrogate the potential of multidisciplinary expertise in developing digital heritage projects. To support this, the project’s methodology includes an iterative design process where subject-specialists* will take part in a series of four co-design sessions.

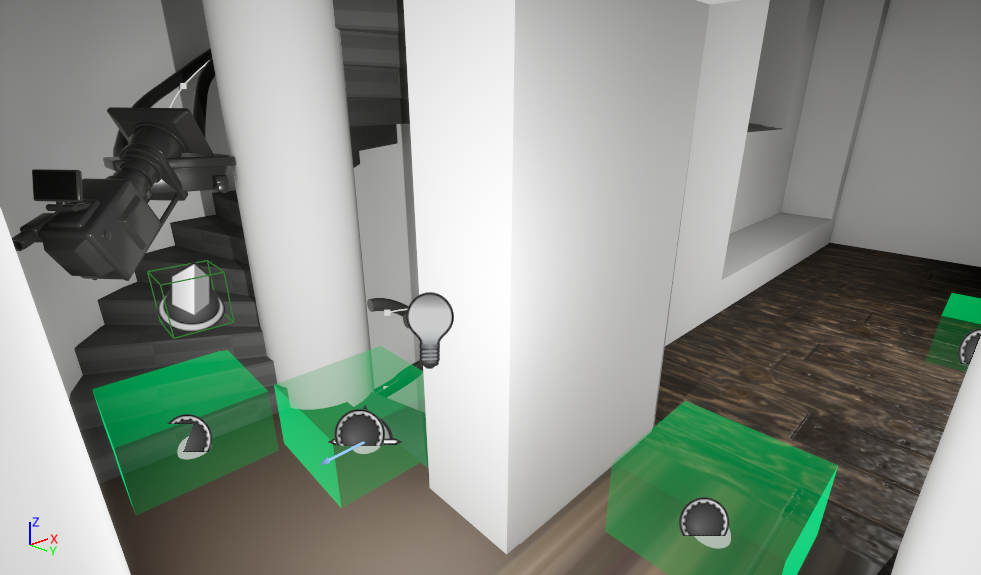

The first co-design session was held on May 22nd, and participants were able to explore a ‘whitebox’ version of the Norman keep and surroundings. ‘Whitebox’ refers to an early stage of a digital reconstruction where a structure’s overall form is created without surface textures, furnishings, or other fixtures. Participants explored the model using large touchscreens and were able to evaluate how the excavation information had been interpreted to date, provide feedback on the current user experience, and make suggestions for how the experience could be developed. The session demonstrated to both the project team and participants the benefits of simultaneously considering the historical data and the audience experience. As Dr Jeremy Ashbee, Head Properties Curator, English Heritage, explained:

I am very interested in how digital media combined with scholarship can be used to improve public access and comprehension of these sites, which even to people like me who have become obsessive about them for decades, still are beguilingly mysterious.

Screenshot demonstrating the development of the underlying user experience functionality including the camera rail system for climbing the staircases and the green travel nodes for touchscreen navigation. (Courtesy of Mike Farrant)

The next milestone for the project will be a public engagement event at this year’s Medieval Pageant and Trail (link) on July 5th where visitors of all ages will be able to explore the reconstruction on screens and provide feedback. Following that, the second co-design session will take place on July 16th.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

- The project team comprises Dr Katie McGown (Principal Investigator), Mike Farrant (Lead 3D artist), and co-investigators Dr Catriona Cooper, Prof Leonie Hicks, Sam Holdstock, and Prof Alan Meades whose combined expertise range from Norman History, Education, Digital Heritage, Exhibitions, to Games Design. To date, the project has recruited participants from organisations including English Heritage, Canterbury Museums, Canterbury Cathedral, Canterbury Council and Canterbury Business Improvement District.