Project leads Paul Pattison and Esther van Raamsdonk give an update on how their project on transcribing and translating of the Seventeenth Century survey by a Dutch Engineer of 22 castles and fortifications.

Now we are reaching the end of our research project – Transcribing and Translating SP9/99: A Seventeenth-Century Dutch Survey of 22 English Castles and Fortifications – we wanted to share a little more about the process of coming to grips with this engrossing manuscript.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

A brief bit of context: the National Archives holds an anonymous manuscript, currently undated but certainly early seventeenth century, which contains a survey of at least 22 English castles and fortifications. This survey was carried out by a Dutch engineer, who clearly spent considerable time in England, as he has adopted several English words (albeit with idiosyncratic spellings). Because of the linguistic and material challenges – the unorthodox Dutch, the difficult handwriting, and the bad condition of the paper – it has never been transcribed and translated. The value of understanding the manuscript, however, is clear. The survey outlines the condition of the castles and fortifications at the time; it provides early modern names of buildings and their elements, some of which are now lost. It also provides suggestions for improvement, some of which we know have later been realised. We can now relate these improvements to the suggestions of the survey. More will be said in due course about some of our findings concerning what we can learn about the history and development of the 6 particular castles that we have now transcribed and translated – Sandown, Deal, Walmer, Dover, Sandgate and Camber – but here we wanted to elaborate a little on the fun and challenges of transcription.

The engineer was from the Low Countries. It is difficult to pinpoint exactly where, but it was likely the southern end of the Netherlands, as the language does not follow the more standardised version of Dutch that by that time flourished in the North. Beyond the language, there is no punctuation in the document, not even a full stop. Almost all text is in phrases; there are no complete sentences; frequently verbs are missing. It reads like a list or a summing up of the engineer’s thoughts as he examined the sites. However, the content is also careful and precise, noting measurements, directions, costs and uses, all accompanied with skilful drawings and plans.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

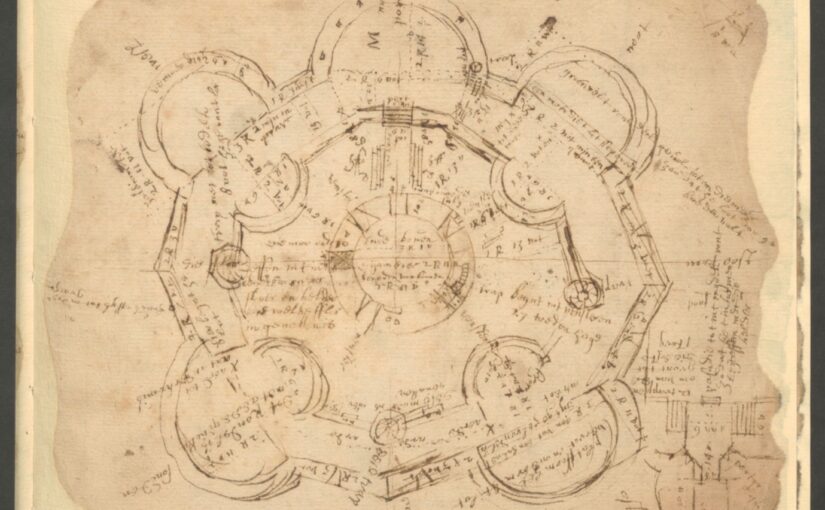

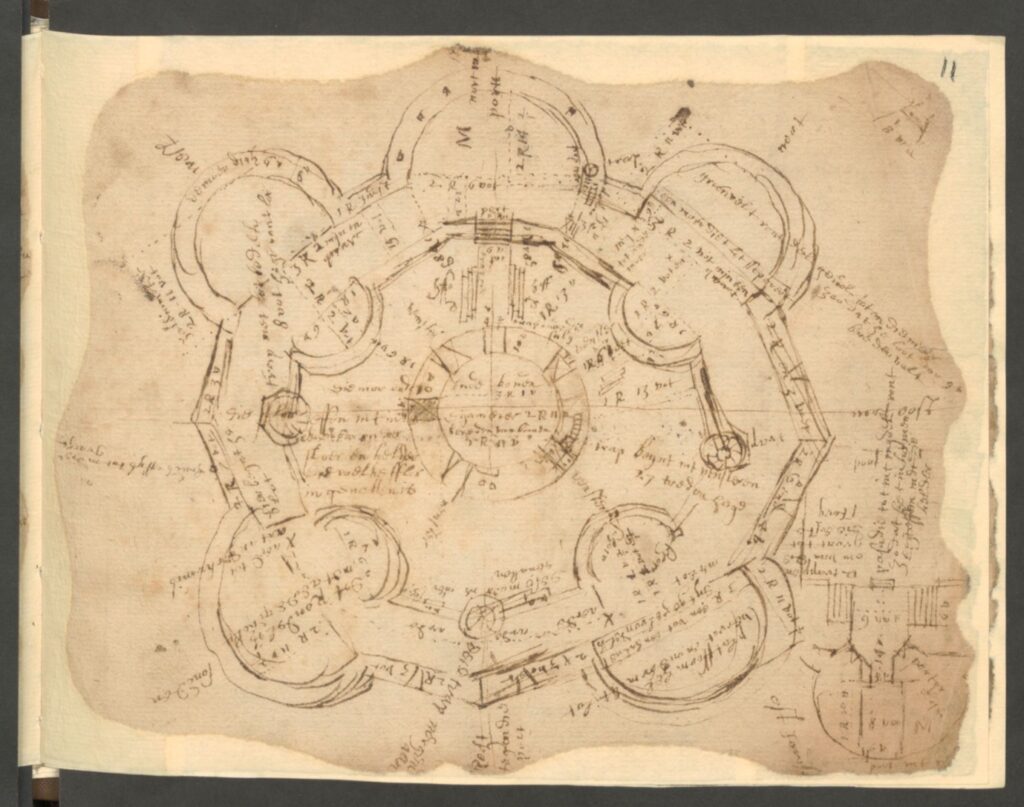

We will give you here two examples from Camber Castle. We have included the engineer’s full sketch plan here but will zoom in on the central keep. Having spent several months with this engineer and his handwriting, it can feel like we know the man quite well. He was often in a rush. This is visible in the way he sometimes repeats the same word in a row, and the density of abbreviations used. In the early modern period, abbreviations were common, and were themselves often standardised. For example, yt for that, or Sr for sir. These could be marked in several ways, but most often in either superscript or with a line above the word. Our engineer liked to break with tradition and places a characteristic C above a word. In my years working as palaeographer, I have never come across this, so we can reasonably conclude that this engineer was not formally trained. That is to say, he did not go to university; for most of the early modern texts that we work with, the authors had received a formal education and conform to the ‘rules’ of writing, but our engineer had worked out his own system of noting deviations. In a similar break with tradition, he uses the C symbol in three ways: to mark an abbreviation, to flag where he has made a mistake, or to indicate an English word and that he does not know how to spell it. Which one of these is the case for individual words is up to us to find out.

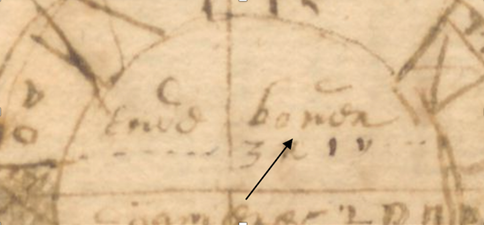

In the image below, there is a good example of the difficulty of these abbreviations or deviations. In the keep of Camber castle, there is written ‘ende boven, …… 3r 1v’. We know there is something strange going on with the word ‘boven’ because of the symbol C. To confuse matters further, this handwriting uses the same letter for v and n, and its e is often written as an o. We therefore assumed that this word would be an abbreviation of ‘benen’ (sometimes written as benéen), meaning ‘beneden’, which is Dutch for beneath or underneath. However, after working on several castles, it did not make sense that he would be talking about a roof beneath a room, and we therefore had to revisit all instances of benen and realised in some cases it had to be ‘boven’, meaning above. In this case the C symbol merely signifies the confusion between n and v, that the engineer himself clearly also suffered from.

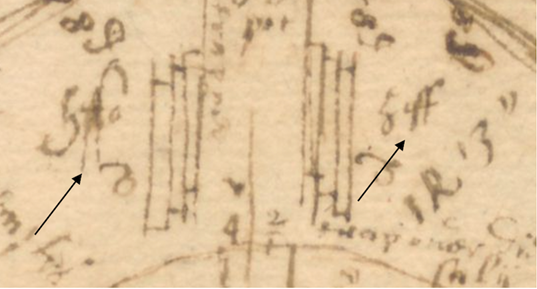

To give an example of the engineer’s haste, or possibly enthusiasm, we can turn now to the marks just above the word ‘boven’ in the previous image. As is clearly visible from the full photo of Camber castle, this was a gifted draftsman. Camber Castle is certainly not the most technically difficult of the castles in the manuscript, but, as ever, his attention to detail and scale is impressive. The care he took in the drawing itself is not always present in his annotations, presumably because these were in draft form. As a result, the distinction between what is part of the drawing and what are notes that were added later is blurred. In the below image on the left, there is a strange mark which can be transcribed as ‘hffo’. This is not even close to an early modern Dutch word. The h also misses its characteristic full loop in the bottom curve. We thought it might be an abbreviation, although the C-symbol is not present, or some sort of mark highlighting an element of the building. It was only after we went over the full transcription several times again, that we realised he had misspelled ‘hoff’, like the word on the right, meaning ‘courtyard’ in Dutch. In his rush he had jumbled the order of the letters and not fully closed his h.

These moments of breakthrough are rather exhilarating. Most of the transcriptions and translations that we have made still have some outstanding ‘curiosities’ to be solved. However, as a result of these idiosyncrasies or oddities, we have been drawn very close to the material and grappled with all aspects of it: the material history, the background of the engineer, the process of surveying these castles and fortifications, and the long history of repair. We are now in the process of puzzling over the new information the survey has brought to light and how it fits with what we already know about these buildings. We look forward to disclosing further updates here, hopefully in fully legible modern English.