The Castle Studies Trust has awarded a research grant to Dr Esther van Raamsdonk (University of Utrecht, Netherlands) and Paul Pattison (English Heritage) to work on an early 17th-century manuscript from the National Archives, concerning fortifications and castles on the south coast of England.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

The manuscript was discovered over 40 years ago by Charles Trollope, following which, the late John Kenyon published a preliminary assessment (Fort vol 11, 1983, pp 35-56), showing that it related to a survey of several coastal fortifications along the south coast of England, mainly those that originated in Henry VIII’s castle building programme in the 1540s. However, the manuscript is in Dutch, so as Kenyon rightly says: ‘translation of the Dutch is required to assess the document’s full significance and to possibly produce a more exact date than I am able to postulate at this moment’ (p. 37). His article examines some of the plans in the document, but there is no engagement with the Dutch text, which is more than 50% of the document. No transcriptions or translations have therefore been made before.

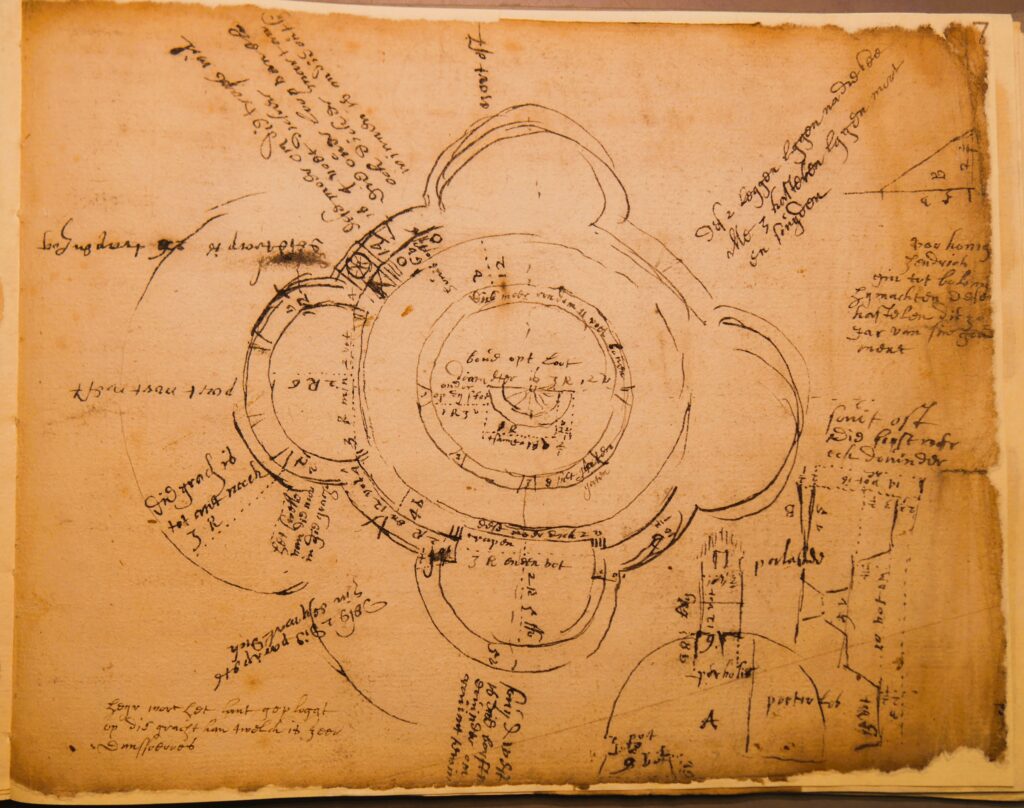

The manuscript seems to be a surveyor’s on-site notebook, comprising fairly accurate and proportioned sketch plans. These beautiful drawings show a highly-skilled engineer at work, and one with a talent for exact survey drawings. These are supported by keyed notes and more detailed explanatory text. It covers most of the main fortifications and castles along the south coast, from Sandown Castle near Deal in Kent to Pendennis Castle at Falmouth in Cornwall.

Paul came across the manuscript several years ago and recently, prior to writing a new guidebook for Yarmouth Castle, Isle of Wight, looked for a palaeographer to transcribe and translate the pages for Yarmouth – enter Esther. Paul is a historic fortifications specialist, and his job is to help to make sense of the translation, as the conversion to English is not always obvious: there are many military and technical terms and sometimes the meaning is not immediately apparent. However, the sketched plans are annotated and keyed, which should help in understanding specific parts of each fortification. Esther is an expert palaeographer, having taught early modern English palaeography courses for some years, and scholar of 17th-century Anglo-Dutch relations. The grant is towards her costs of transcribing and translating the text and notes. It is not an easy task. The hand is a difficult one and several pages are faded. The Dutch engineer spent some time in England and the result is a hybrid language, a phonetic (for Dutch readers) spelling of English words. The document also functioned as a shorthand for the author, using non-standard abbreviations, idioms, and little drawings. The exercise is therefore not of a straight-forward transcription but requires quite a bit of puzzling.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

As mentioned, we used the Yarmouth example to see what information we could gather from the manuscript. From this test case we know that the surveyor was commenting on condition and making recommendations for repairs and changes. Because of the detailed map and key, we could pinpoint the function of some rooms that were hitherto unknown. We look forward to see what further secrets the document will reveal about the other buildings.

The funding will enable us to examine a sample of the manuscript covering several sites in the Cinque Ports area of jurisdiction – Sandown, Deal, Walmer, Dover, Sandgate and possibly Camber. All of these are well known to Paul, and it is hoped that significant details about the condition of each castle or fortification will be forthcoming, for comparison with other contemporary accounts in English, to see and understand where this survey fits and whether or not it resulted in any repairs or additions on each site. John Kenyon thought it might date to the 1620s: we would like to try and confirm that, or otherwise, by comparison with earlier and later surveys, and to establish the political context for its commissioning. This will lead to at least one provenance article. The transcriptions (some of which will be published) will also provide a very valuable snapshot of the south coast fortifications 80 years or so after their creation, and form a test for the usefulness of going further and transcribing the whole manuscript. There is an exciting journey ahead.