In the second of two articles, Dr Christian Clarkson, Heritage Consultant at Simpson Brown takes a look at the work she undertook at Carrickfergus Castle.

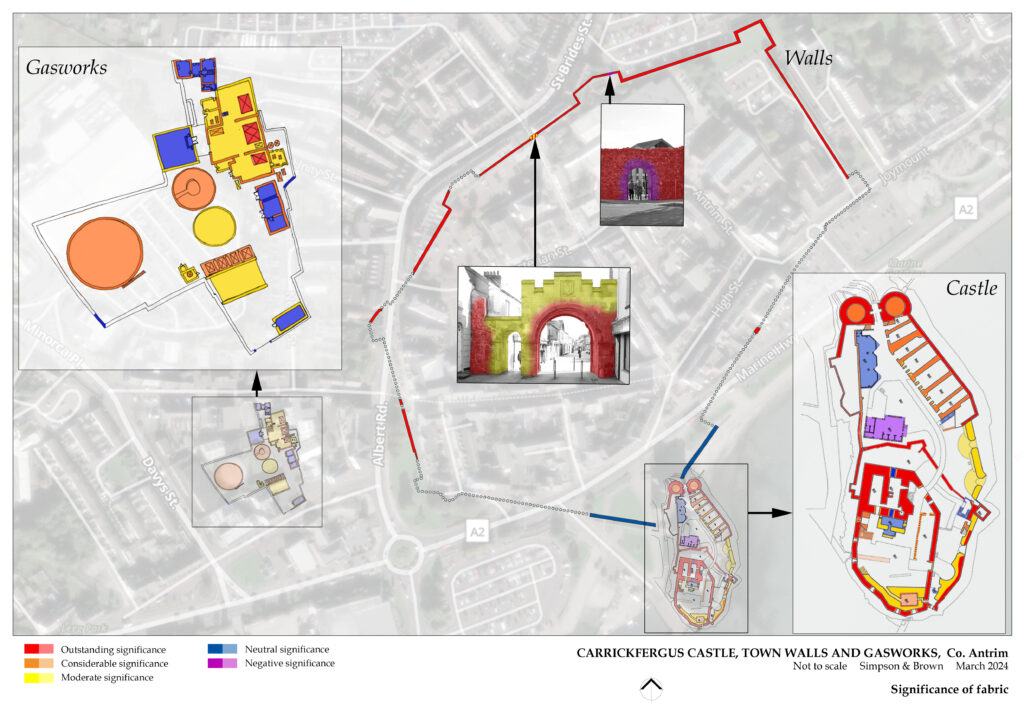

In 2023, Simpson & Brown were engaged as heritage consultants to write conservation plans for three historic structures in Carrickfergus, Co. Antrim: the Elizabethan town walls; the Category A-listed historic gasworks museum; and Carrickfergus Castle. Situated dramatically on the coast of Belfast Lough, Carrickfergus Castle dominates the town and is one of the most impressive castles on the island of Ireland. Simpson & Brown’s work was part of the Carrickfergus City Deal, an investment programme which seeks to put heritage at the heart of a regeneration of the town.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

This programme brought into sharp focus the key concern of our work as heritage consultants: managing change. Some degree of change would be needed at the castle to achieve the aims of the deal, and this change would have to be executed with as little negative impact as possible on the qualities which make Carrickfergus Castle special, its cultural-heritage significance. Our job as heritage consultants was to express that significance, and consider how the proposals of the City Deal might impact it.

Our work had to be based on a solid understanding of the history of the castle, and in the case of Carrickfergus we were lucky enough to have decades of quality scholarship at our fingertips with regards to its medieval fabric, in particular in the work of Tom McNeill and Ruairí Ó Baoill (for example, the former’s work with Sarah Gormley as published in CSG Journal 30, 2016-17). Naturally, however, all medieval fabric at the castle would be significant to a very high level: more complex, in some ways, was considering the degree to which, and the ways in which, later fabric at Carrickfergus is significant.

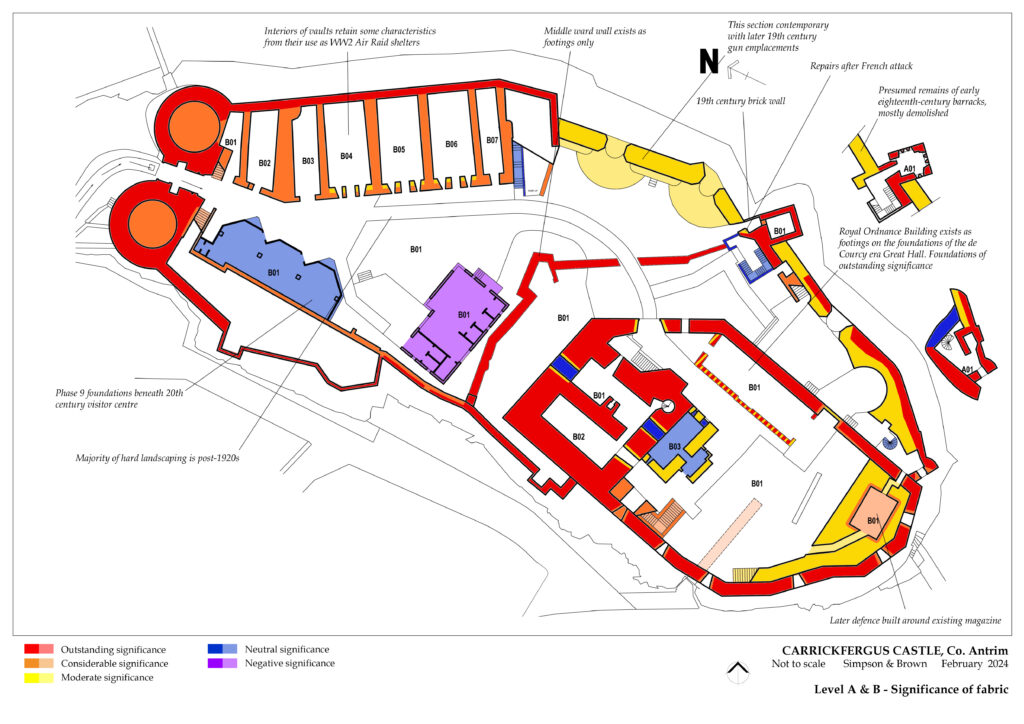

Although there is evidence of prehistoric activity on the same site, the history of the castle itself begins in the late twelfth century when it was founded by John de Courcy shortly after his 1177 invasion of Ulster; much of what is now the Great Tower and inner ward was constructed at this time. The middle ward wall was built by King John in the early thirteenth century, and the outer ward and gatehouse by Hugh de Lacy, probably around the 1230s. While the castle had grown effectively to its full extent by the middle of the thirteenth century, its military and architectural life was only just beginning. Extensive work was carried out in the later sixteenth century to equip the building to withstand and return the heavier artillery fire of the period. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries it was used as a prison and as a garrison, and in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century its defences were significantly upgraded including the construction of the Grand Battery on top of the sixteenth-century vaults. In the later nineteenth century, a small railway was built to bring supplies up and through the inner ward wall from the adjacent pier, and we found that it was likely that changes to fortifications at this time had been greater than previously thought: our fabric analysis showed that it was likely that masonry on the north wall was contemporary with neighbouring gun emplacements, meaning that this areas was more comprehensively rebuilt at this time. The castle even remained in service through the first and second world wars, providing military defence in the former and civilian air raid shelters in the latter. In the later twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the site has seen some fabric changes including the construction of the 1990s visitor centre, and the exceptional new roof of the Great Tower, mentioned in CSG Journal 35 (2021-22).

While our archaeology team reviewed all documented archaeological work on the castle site, the heritage consultancy division worked on adding as much as possible to our knowledge of the later life of the castle, including hunting archival photographs and documents at the Public Record Office in Belfast, PRONI. Nineteenth-century photographs revealed the form of buildings and structures which have since been lost, such as the Royal Ordnance Building on the site of the original great hall in the inner ward, and nineteenth-century garrison buildings where the visitor centre currently stands. The visitor centre had been constructed without a programme of archaeological work, and there was potential for change in this part of the site as part of the City Deal: one proposal considered removing the castle visitor centre to replace it with a multi-site visitor centre outside the castle itself. Knowing what stood on this site prior to the existing visitor centre informed potential future archaeology in this area. The removal of the visitor centre could be a potential improvement to the site: while the existing building solves the problem of accommodating a shop and ticket office reasonably well, a clear view towards the keep from the gatehouse would be preferable in terms of recreating the historic experience of arriving in the outer ward.

The Royal Ordnance Building appears as a gable-end in historic photographs, constructed of rubble with brick window surrounds, and a footprint approximately that of the medieval hall. The City Deal considered the possibility of constructing visitor facilities on this footprint: knowing some details of the size and appearance of the Ordnance Building could inform what a new building here might look like, although we felt that it might be challenging to accommodate plant, for example, in a space as sensitive as the inner ward.

Ultimately, our analysis suggested that while the highest level of significance should be ascribed to the medieval fabric, there was still significance at the site derived from its later military architecture, including for example the WW1 gun emplacements. We did find a negative effect on heritage values from some contemporary changes at the castle, and recommended that the important functions that those changes served be accommodated in a way which better complemented the fabric. These included the existing stairs and events space, as well as the temporary education building straddling the footings of the middle ward wall: our assessment can act as a starting-point for discussion of change in these areas. Where we consider how to protect and enhance heritage significance, this can come into conflict with requirements for, for example, sustainability or accessibility: our documents are designed to equip our clients with the heritage knowledge they need to weight this against these other important needs, to generate the best possible outcomes both for the building, but also the community.