Castle Studies Trust patron John Goodall explains the reason behind his latest book The Castle (Yale University Press) using the intriguing example of what happened to Caister Castle after the death of Sir John Fastolf, the castle’s owner.

Those who have seen a copy of The English Castle (2011), which I published more than a decade ago, may be surprised to learn that it was originally intended to be a short book. The attempt to tell the story of the architectural development of the castle from the Norman Conquest of 1066 to the Civil Wars of the 1640s, however, inexorably and necessarily transformed it into a long and richly illustrated one. So long and so richly illustrated that, when it was completed, I never thought I would wish to return to the subject.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Several friends and at least one reviewer, however, observed that the story it told about the history of the castle was incomplete. If the castle was—by my own definition—the residence of a noble made magnificent by the trappings of fortification, then what was there to say about such buildings in later centuries? They were right, of course, and this new book The Castle. A History is an attempt to complete a story that my previous book—for all its length and scale—only partially told.

Rather than continue the narrative in the same form, however, and produce another door-stopping volume, I thought I would try and condense the whole story of the castle from beginning to end in a single and much shorter volume. In this sense, this second book on the subject of castles is actually cast in the intended form of the first that I planned more than a decade ago. To make this possible I also decided to approach the subject in a way that I hope will strike readers as both unexpected and engaging.

Presented here are effectively a series of anecdotes organised in a huge chronological span of two millennia and drawn from every kind of source, from chronicles to sermons, poetry to building accounts, and novels to correspondence. All of them are about castles or take place within the context of these buildings. There are also some images that are treated in the same way. The result is a story presented through many different modes and voices across a span of over two millennia.

Part of the joy of this approach is that the book can be read in many different ways, either as a volume that the reader can dip into casually at any point or as an overarching narrative. More importantly, however, it allows for the exploration of specific detail in a way that is impossible in a conventional narrative history. In the process, the human dimension of the past is also brought to the fore. As an added benefit it allows for the exploration of small episodes and the specifics surrounding them that would be impossible in a conventional narrative history.

What could be better as a taster for the volume, therefore, than take a relatively well known anecdote about a siege that didn’t make the final cut for reasons of length and present it in the formula adopted in the book.

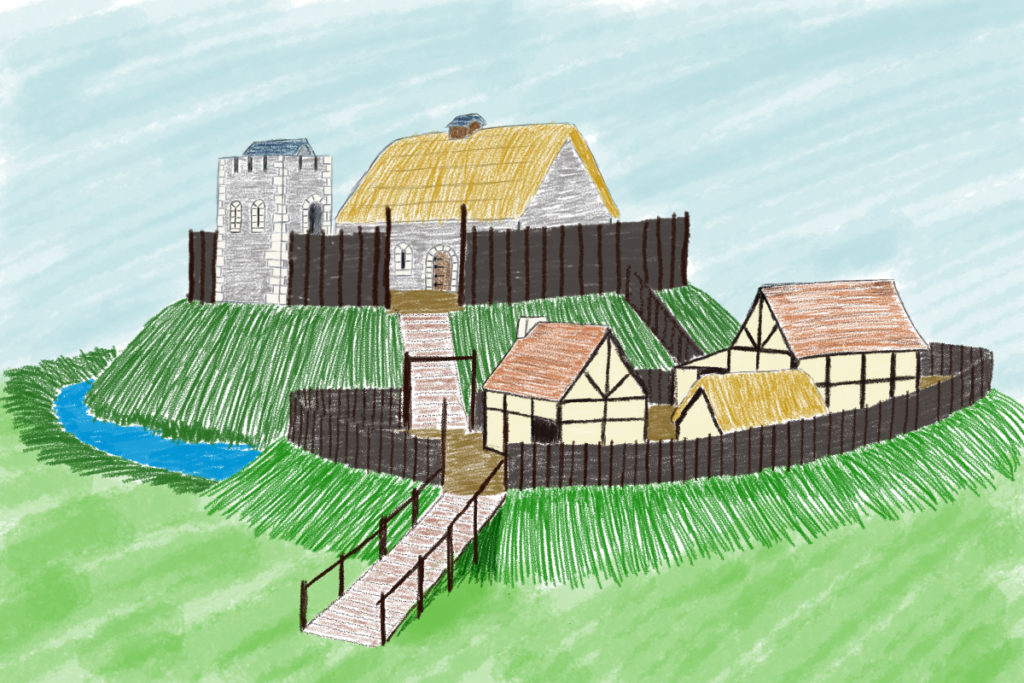

In the autumn of 1459 the childless Sir John Fastolf, a wealthy veteran of the French wars, tried from his deathbed to finalise the details of a long-discussed proposal to turn his seat at Caister—variously described as a ‘great mansion’, ‘castle’, ‘manor’ and ‘fortress’—into a Benedictine Priory and almshouse. When he died on November 5, his trusted administrator John Paston announced that Sir John had issued a final will by word of mouth. This nuncipative will gave Paston control of all Sir John’s property and tasked him with founding the priory. We will never know the truth of Paston’s assertion. Given the value of what was at stake, however, not to mention England’s descent into the Wars of the Roses, it was never going to go unchallenged.

After the Battle of Edgecote on July 26, 1469, Edward IV was briefly imprisoned and royal authority collapsed. A wave of violence broke as individuals across the kingdom took the opportunity to settle scores. Among them was the Duke of Norfolk, who decided to seize Caister by force. The ensuing siege lasted about three weeks and details of it are recorded in the writings of a former secretary of Sir John Fastolph, the scholar, historian and topographer, William Worcestre. He was an excluded executor of Sir John’s will:

Memorandum that at the feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Mary [15 August] 9 years ago was the siege of Caister; Saint Bartholomew’s [Day, August 24] was a cruel day with guns fired at the castle [castrum]; the siege lasted for five weeks and three days.

Here follow the names of the men at arms besieging the castle and fortalice [castellum et fortalicium] of Caister Fastolf, beginning on Monday, [August 21] before the feast of Saint Bartholomew in the ninth year of King Edward IV, the King being at Coventry; and the siege lasted until September 27.

John, Duke of Norfolk… [followed by a list of 37 other knights and squires].

The names of certain defenders of the siege against the Duke:

John Paston junior, esquire, defending the siege in place of John Paston knight his brother, during his absence, being with:

Dawbeney esq slain with a quarrel

Osbern Bernay esq

Valets: Osbern of Caister valet; Sander Cokby of Maltby valet; Richard Tolle valet; Mundynet, born in France; Thomas Salern of Caister; servants of John Paston junior John Vincent; W. Vincent; W. Wod; N, Bylys; Robert Owmond of Maltby. Davy Coke, servant of John Fastolf; John Roos of Filby; John Osbern of Filby; John Norwood; Raulyns, a stranger; William Peny, a soldier from Calais; John Loe of Calais; Mathew, a Dutchman; Thomas Stompys, handless, and wished to shoot for a noble; John Pampyng of Norwich; John Chapman, soldier of the Duke of Somerset; J. Jaksone of Lancashire; J. Sparke of Marsham

And first the said Duke John, before laying siege to the said castle, a week beforehand, sent Sir John Heveningham, knight, a cousin of Sir John Fastolf, to John Paston, junior Esquire, lieutenant of his brother, John Paston knight, for the safekeeping of the said castle for the use of his brother during his absence on service and on business…. The Duke said that he had bought the castle from a certain accursed William Yelverton Justitiar of Norfolk named one of the executors of Sir John Fastolf knight and lord of the castle, although it was against his will and testament that it should be sold, for he had ordained in his testament that it was to be a house of prayer and for poor people, to be founded to pray for ever for his soul and those of his parents. The said lieutenant of Caister refused to deliver up the castle, for that he had not taken custody of it from the Duke, but only from John Paston his brother. Afterwards, within ten days, that is on the said Monday, the Duke himself with his army to the number of 3,000 armed med laid siege to the castle. Three parts of it were under fire from arms called in English guns and culverins [gonnys culveryns] and other pieces of ordnance of artillery, with archers etc.

William of Worcestre, Itineraries (trans. J. Harvey)

The list of the garrison is curious because it shows that besides a force of locals and servants (including the handless Stompys, who ambiguously wished to ‘shoot for a noble’ or gold coin) there was a smaller group of mercenaries, many of them with experience in Calais, then an English frontier town in France. The latter appear to have been given command of sections of the fortifications and in the months before the siege helped train the former. The fighting seems to have been restricted to bombardment followed by negotiation, at the end of which the castle capitulated. Beside the unfortunate Daubeney, whose brass survives at nearby Sharrington Church, two of the besiegers were also killed by a single cannon shot. The Duke issued terms of surrender on September 26 that:

John Paston and his said fellowship being in the said manor shall depart and go out of the said manor without delay, and make thereof deliverance to such persons as we will assign, the said fellowship having their lives and goods, horses and harness, and other goods being in the keeping of the said John Paston, except guns, crossbows, and quarrels, and all of the hostelments to the said manor annexed and belonging…

September 26, 1469, passport to the besieged

The siege was one episode in a long battle over Fastolf’s will but Caister never became a monastery (a 20th-century equivalent would be the donation of a house to the National Trust). Instead, much of his land was used to endow Magdalen College, Oxford.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

The Castle by John Goodall is published by Yale University Press and available via all good bookshops.

Featured Image: Caister Castle Great Tower, copyright John Goodall