Between November 2022 and March 2025 the research project Where Power Lies explored the archaeological evidence for the origins and early development of England’s medieval lordly centres. Funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, the project characterised material expressions of elite authority across c.800-1200. This blog summarises some of the project’s key findings and outputs, and provides updates on continuing work.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

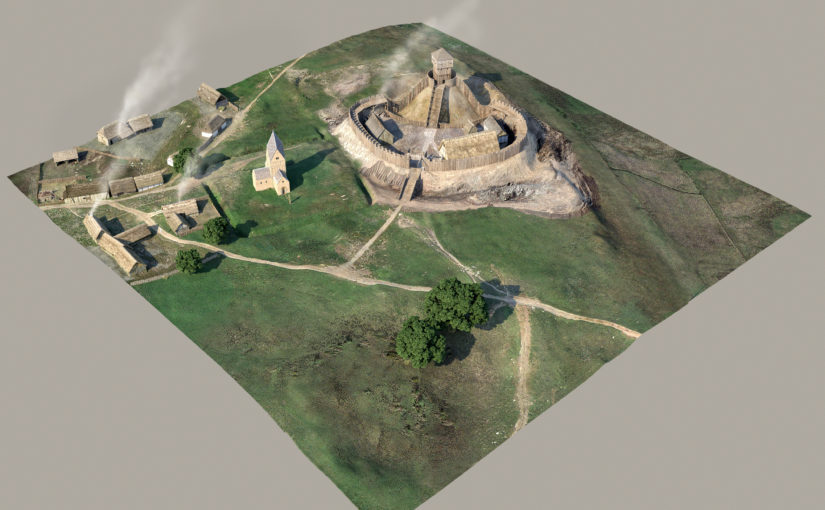

For a little over two years the research project Where Power Lies investigated the archaeological evidence for the emergence of England’s medieval ‘lordly centres’: places in the landscape that elite families developed primarily for their own self-aggrandisement. The programme was keen to conceptualise early castles (c.1066-1200) as a manifestation of these elite enclaves, albeit ones that were in many ways distinctive from other sites. Where Power Lies examined the material at a number of scales, firstly with national datasets integrated into a GIS in order to identify possible regional distinctions. It was quickly realised, however, that a more detailed approach was required to interrogate data more meaningfully, so the project team examined two ‘macro regions’ more closely. One region covered counties in southern and western England, the other incorporated the historic counties of Yorkshire and Lincolnshire. Information was extracted from the Historic Environment Record of each county, and interrogated to assess the validity of a site identified as a lordly centre and an assessment made as to its character and date.

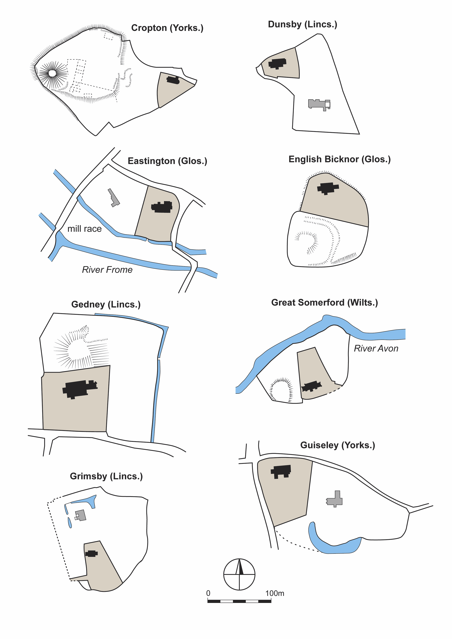

Although the ‘cleaned’ dataset for the two macro regions still presented challenges for interpretation, some meaningful patterns could be identified. Firstly, it was clear that lordly centres featuring a closely paired church and residence occurred more frequently in areas of dispersed settlement. This finding is supported by analysis of the nationwide dataset of early castles, with significant numbers located in areas of very low to low settlement density. These patterns highlight that lordly foci were were at the very least embedded within a diversity of settlement landscapes and were not a peculiarity of nucleated villages in ‘champion’ countryside, as has sometimes been assumed. Secondly, it was evident that major watercourses were of great importance in the establishment of lordly centres; while significant quantities of water would have been needed for domestic and agricultural purposes, substantial rivers and streams also seem to have been exploited from an early date to power watermills (Figure 1). Such mills were a fundamental foundation of lordly authority, representing a centralisation of a key economic resource and symbolic of the primacy of particular families over others.

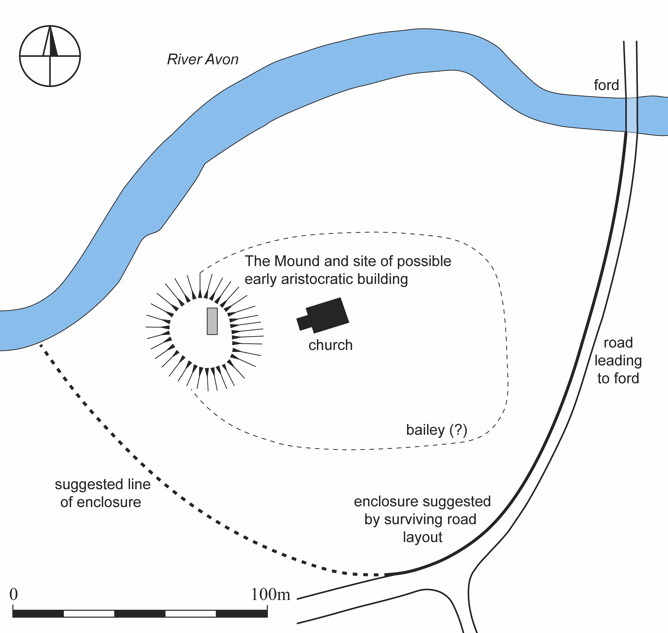

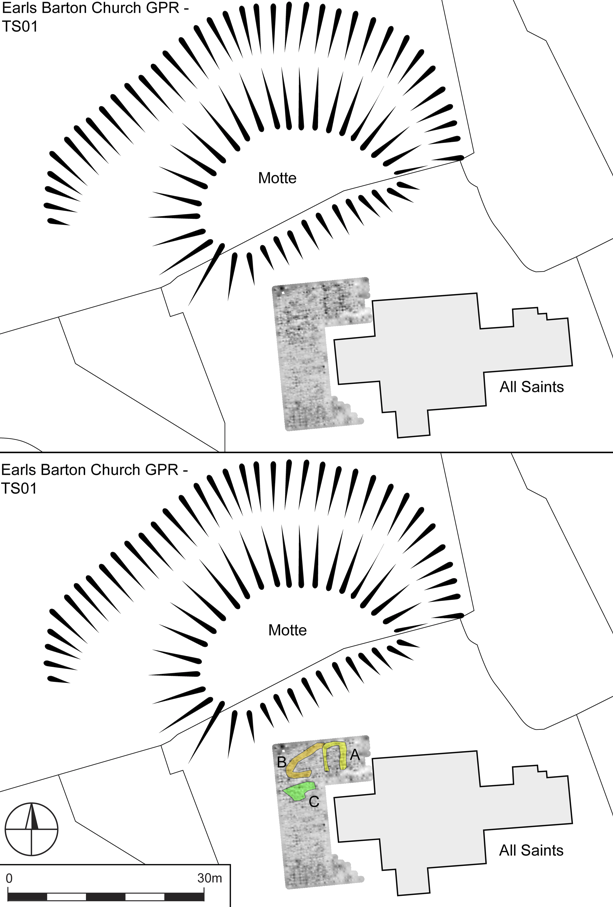

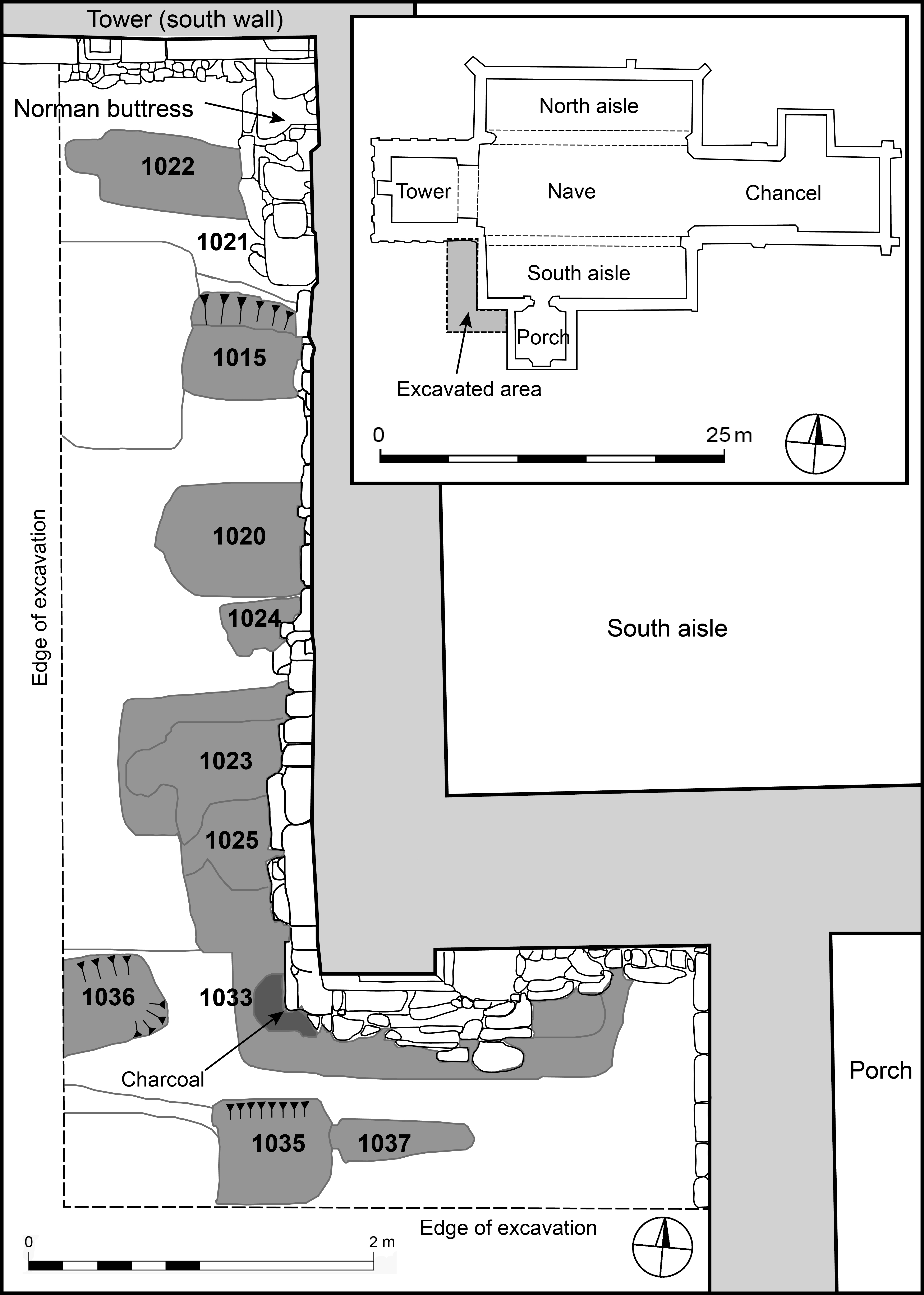

Eight locations offering especially high potential were chosen as case studies warranting further investigation, with a combination of approaches deployed to understand them more thoroughly; these included detailed desk-based research, geophysical and topographic survey, standing building assessment, and targeted excavation to facilitate optically-stimulated luminescence profiling and dating of earthworks. Among the case studies was the motte at Great Somerford (Wiltshire), surveyed using a ground-penetrating radar which found a stone-built structure located within the earthwork. This feature had previously been excavated in the 1950s and although ‘windows with Norman features’ were recovered, the exact character of the structure remained uncertain. Our survey demonstrated that the rectilinear building is orientated broadly north-south, apparently discounting its identification as an early church (Figure 2). Situated at some depth within the north-east part of the motte, this feature is perhaps best understood as a chamber and one that apparently preceded construction of the castle. A similar situation is apparent at Earls Barton, Northamptonshire, where a comparable stone-built rectilinear building seems to have been followed by construction of Berry Mount (Figure 3). Our survey here also located a second church, less than 5 miles from the celebrated tower-nave. At both of these sites, then, mottes seem to have been raised over earlier stone-built chambers; while further work is required to phase site sequences more closely, the possibility is that these castles were raised after a period of elite Norman occupation, perhaps in the twelfth century, rather than in the immediate aftermath of the Conquest.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Our work continues at Earls Barton, with two generous grants from the National Environment Isotope Facility supporting investigation of ten rock-cut burials from the churchyard, excavated in the 1970s (Figure 4). The majority of the radiocarbon work has already taken place, and our tentative interpretation phases these graves to the eleventh and early twelfth centuries. Results of isotope analyses are expected soon, which will hopefully clarify the migration and dietary histories of what is apparently Earls Barton’s earliest medieval burial population. A final site in which a castle was investigated was at Saintbury, Gloucestershire, which was reported on in a previous blog-post. The project team are aiming to obtain radiocarbon dates for human remains recovered from animal burrowing at Saintbury’s motte and bailey, in order to ascertain whether the monument was erected on a prehistoric burial mound.

Where Power Lies has generated several outputs, all of which are free to access. Our project database, which includes all geophysical survey and GIS data as well as individual site reports, is hosted by the Archaeology Data Service and we have published papers in The Antiquaries Journal, Early Medieval Europe and Medieval Settlement Research. Duncan Wright and Oliver Creighton are also writing a monograph, which will be published in 2028 with Bloomsbury. The project team would like to thank once again the Castle Studies Trust for supporting the project throughout, and for funding the pilot phase of work at Laughton en le Morthen, South Yorkshire. We hope that our work has in some way advanced understanding of lordly centres, and that the study of early castles as a phenomenon has been invigorated and enriched by our findings.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Further reading and resources

Gould D., Creighton O., Chaussée S., Shapland M., Wright D.W. 2025: ‘Where Power Lies: Lordly centres in the English Landscape c.800-1200, The Antiquaries Journal 104, 72-106. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003581524000350

Gould D, Creighton O, Chausée S, Shapland M, Wright D.W. 2024: ‘Where Power Lies: The Archaeology of Transforming Elite Centres in the Landscape of Medieval England c.AD 800-1200’, Medieval Settlement Research 39, 80-92. https://archaeopresspublishing.com/ojs/index.php/msr/article/view/2715

Wright, D.W., Creighton, O., Gould, D. 2024: ‘Data from ‘Where power Lies: The Archaeology of Transforming Elite Centres in the Landscape of Medieval England c. AD 800-1200’, 2022-2024 [data-set]. York: Archaeology Data Service [distributor] https://doi.org/10.5284/1122293

Wright, D.W. Creighton, O.H., Gould, D., Chaussée, S., Kinnaird, T., Shapland, M., Srivastava, A. and Turner, S. 2025: ‘The power of the past: materialising collective memory at early medieval lordly centres’, Early Medieval Europe, https://doi.org/10.1111/emed.70004

Wright D.W., Bromage S, Shapland S, Everson P, Stocker D. 2022: ‘Laughton en le Morthen, South Yorkshire: Evolution of a Medieval Magnate Core’, Landscapes 23(2), 140-165. https://doi.org/10.1080/14662035.2023.2219082