William Wyeth, Properties Historian at English Heritage Trust and project lead on the Castle Studies Trust funded project to geophysically survey Warkworth Castle explains what he hopes the survey will achieve.

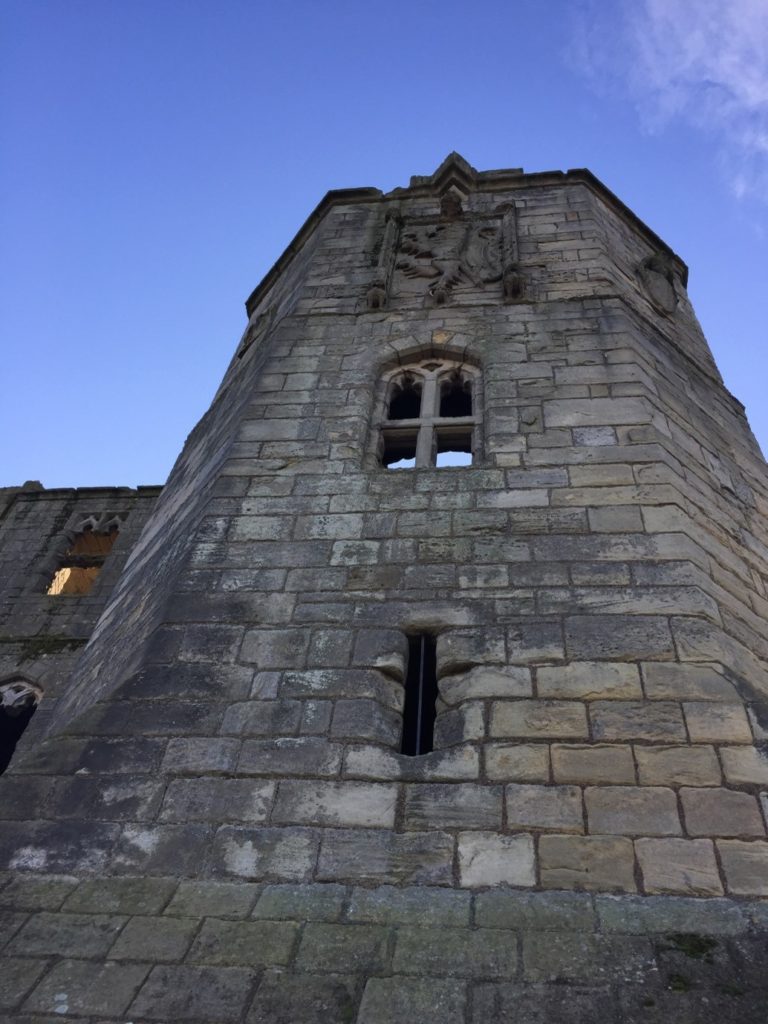

In 2019 English Heritage, a charity which looks after over 400 historic properties and sites across England, began a project to change the way in which the stories of the people and buildings at Warkworth Castle in Northumberland were told. The castle is a popular destination in the county, and is both connected with notorious figures from the past as well as featuring an iconic piece of medieval architecture and design in its late 14th-century Great Tower.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Warkworth is located at the foot of a narrow loop in the River Coquet, in coastal north-eastern Northumberland, about 25 miles north of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne and 30 miles south of Berwick-Upon-Tweed, themselves both significant fixtures of the late medieval history of this area. Just north of the castle proper and nestled on three sides within the river loop is the small village of Warkworth, arrayed in quite typical medieval layout. At the north end of the high street, sitting on a rough north-south axis, is the parish church of St Lawrence, probably an early medieval foundation, as well as a bridge with a toll-collecting tower built in the later 14th century. South of the church, numerous narrow parallel plots of land spread out at right angles from the high street. The southern trajectory of the street is abruptly broken by the enormous motte (earthen mound) of the castle, which acts to physically separate the village from the land south of the river.

Among the most famous historical figures connected to the castle was Henry Percy, eldest son of the 1st Earl of Northumberland, though he is more familiar to us today as Harry Hotspur. The origin of his martial nickname is not certain, but is accounted for in several traditions, all of which confirm that they drew from his short-tempered and violent character. One later 16th-century source rhythmically noted “For his sharp quickness and speediness at need / Henry Hotspur he was called in very deed.”

Though the early history of the Percy Northumberland earls and associated figures will form a key part of the story of the castle when the interpretation project is completed in 2022, other questions about the castle, and especially its earlier history, remain as yet unresolved. Among these is the relationship of the earthworks – the motte and bailey – with the stone structures atop them, the oldest of which date to the later 12th century. The Castle Studies Trust has graciously agreed to fund a geophysical survey of much of the castle earthworks to resolve three big questions.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

The first touches upon the motte, which features the Great Tower of the 1370s, but was probably topped by an earlier structure. By assessing buried deposits around the tower, we aim to reveal traces of this earlier structure. But we also want to establish evidence for the means by which the Great Tower may have been provisioned, via a secure door to the motte-top outside the enclosing curtain wall which gave access to storage areas for beer and food in the tower’s north-west segment.

The second question relates to the bailey. In common with other castles of this type, the bailey was filled with buildings, often (as at Warkworth) in their earliest phases arrayed along the inner face of the enclosing wall. But were there buildings here before, or were there also buildings here from later periods, but for which above-ground evidence has been lost? Findings from the survey here will greatly influence how we understand the formal approach to the bailey’s principal buildings – its Gatehouse, Great Hall and Chapel – but also the late medieval Great Tower. The results may also shed light on the peculiar overhauling of spatial arrangements in the bailey occasioned by the construction of a 15th-century Collegiate Church which straddled the span of the bailey, arguably fundamentally changing how the castle was to be experienced.

The last question also relates to the bailey, but here to a strip of the bailey which sits outside the embrace of the late 12th-early 13th-century stone curtain wall, on the eastern side of the castle. The omission of this area from enclosure is unusual, though it is not without analogies from elsewhere, which suggest areas like this could contain gardens. It may be instructive that just within the bailey and adjacent to this strip was the location of late medieval stables – perhaps this area came to be used for the grazing of horses, though whether this was its original intended purpose remains to be seen. In addition to all of this, however, is the possibility that when the motte-and-bailey was built, perhaps well before the earliest stone parts of the castle were erected, the earliest enclosing wall of the bailey also embraced this eastern strip, thereby creating a larger bailey than the present one.

We hope that the survey will allow us to answer at least some of these questions. Whatever the outcome, it is certain that the results will help change how we understand the story of Warkworth Castle and its previous inhabitants.