Dr Will Wyeth, English Heritage property historian and project lead on the two geophysical surveys the Castle Studies Trust funded on Warkworth Castle, looks at what the surveys reveal and equally importantly don’t reveal about the castle.

The results from two geophysical surveys in and around Warkworth Castle have now been digested and synthesized. The first survey sought to explore evidence for subsurface remains of the castle earthworks. The second survey examined a field called St John’s Close, sited within a corner of the medieval park attached to Warkworth Castle. Both surveys are intended to inform English Heritage’s on-going project to improve the way the history at the castle is explored and shared with visitors. Here, we share some of the highlights of these surveys: for the full discussion of the results, you can read the full report here.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

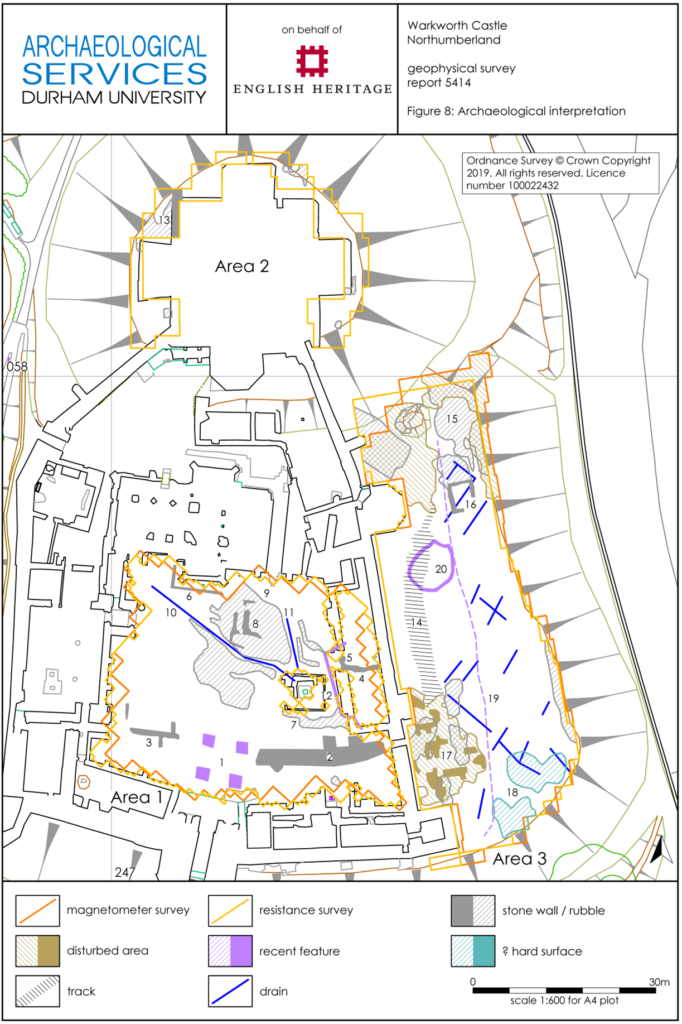

The first survey targeted three areas of the castle. The first was the top of the earthen mound, or motte (see a phased site plan here). Our aim here was to establish the presence or any subsurface features which may relate to any structures pre-dating the present late 14th-century Great Tower (Figure 1). Our results here were inconclusive: the subsurface examination certainly revealed a feature, perhaps a drain or path, associated with the postern of the present Great Tower (Figure 2). Other features may represent building or demolition rubble, but it’s not clear which.

The second area of the castle earthworks to be examined was a portion of the castle’s raised bailey platform, east of the enclosing curtain wall presently dated to the late 12th-early 13th centuries. The earthworks of the bailey of Warkworth Castle pre-date any stone buildings known to survive at the present castle: this is because the earliest structures – among them the curtain wall – do not embrace the entirety of the earthworks (see a phased site plan here).

Our research question here was to establish why this eastern portion of the bailey was left unenclosed, upon the construction of the enclosing curtain wall. Here, again, our results were inconclusive with regards our research question, though the survey did throw some light on possible uses of this space in the later medieval-early modern period. The survey detected a trampled path from the area east of the eastern curtain postern, south of the 15th-century stable building, heading northwards, respecting the projecting mass of the 1290s Grey Mare’s Tail Tower (see feature 14, Figure 4 ). The relative phasing of this feature does not tell us a great deal, except that the path may post-date the construction of the Grey Mare’s Tail Tower. It may also suggest that the postern in the curtain wall, currently dated to the late 14th century, could be coeval with the Grey Mare’s Tail Tower, or it may have replaced an earlier iteration. This is the earliest possible arrangement, as the path could also be more recent in date.

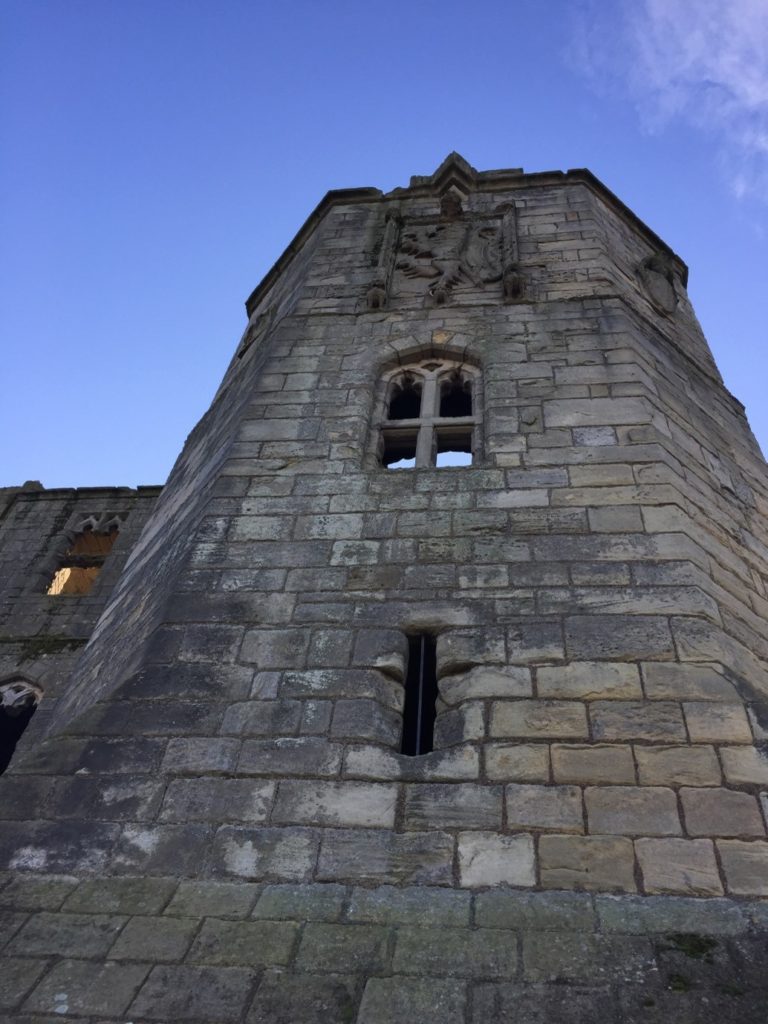

The final portion of the castle earthwork survey sought to establish the location and extent of features within the enclosed portion of the bailey (‘Area 1’, see Figure 4). Uncertainty remains as to the configuration of the bailey before a major phase of construction presently dated to the 15th century. This substantial campaign of building incorporated the construction of the compressed collegiate church (perhaps never completed) with exquisite covered passage, and a comprehensive rebuilding of the eastern portions of the Great Hall, Chamber block and chapel in the bailey, of which the finest surviving portions are the Lion’s Tower and the Little Stair Tower (Figure 5).

The most substantial, and perhaps important, finding of the geophysical survey of the earthworks relates to feature 2 (see Figure 4). Located in the south-eastern quarter of the bailey, it comprises a substantial segment of buried wall or robbed wall foundations, approximately 22m long (on an east-west axis) and c.2m thick. Though the feature stops short of the bailey curtain wall here, it clearly blocks the east curtain postern already mentioned, and therefore may very well pre-date it. The massive character of this feature suggests it may have belonged to a substantial, multi-storey building. Feature 2 also appears to meet the curtain wall at a right angle, with one possible implication being that it may have formed one wall of a square- or rectangular-plan building, which was demolished to make way for the present curtain wall. Curiously, although the castle is not very extensive, the concentration of known high-status buildings from the later 12th-century onwards is on the bailey’s western side. If feature 2 relates to a high-status building, it is unusual for being located in the eastern part of the bailey. Several other features were located within the bailey; these are discussed in the full report.

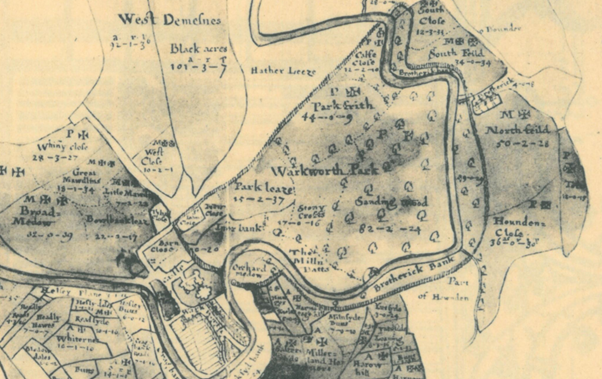

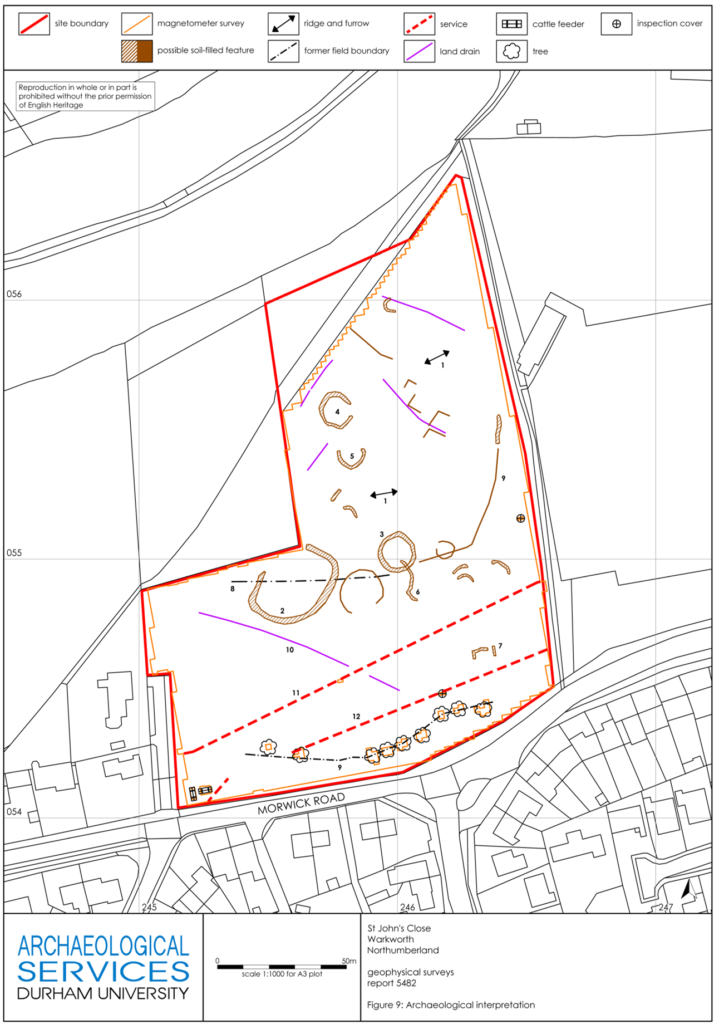

The second area examined by geophysical survey comprised part of the park of Warkworth Castle. The earliest record of the park is dated to the 13th century, but a park at Warkworth may have existed earlier still. Hogdson’s History of Northumberland, which assembled extensive records from the Alnwick Castle archives and elsewhere, offers a rich picture of the late medieval administration of the park, with records of repairs, infringements, agistments (a one off payment by a livestock owner to graze on the land of the landowner) and the collection and sale of underwood all recorded in 15th-century documents. The earthworks of the castle park have yet to be comprehensively mapped, but a portion of the south-east corner of the park, fossilizing the boundary of an historic field within the park called St John’s Close, does survive (see the previous Warkworth blog post for photos of these). This field was chosen as the target of geophysical survey to determine the survival of any features or buildings associated with the medieval park. Research on castle parks has demonstrated that they could feature a broad variety of structures, and were not simply enclosed areas. A further research goal was to ascertain the precise location of a documented park gate attested in a 17th-century estate map (Figure 7), which could represent the closest point of access into the park enclosure from Warkworth Castle.

Unfortunately, the survey results did not yield answers to the questions we posed regarding any medieval features within the area of parkland surveyed, nor was it possible to decisively establish the location of a park gate. The most significant find was in the form of several round features, either enclosures and/or hut circles, which are very likely prehistoric in date (Figure 8). A walk-over of this area confirmed that they were not visible at ground surface level, being concealed by ridge-and-furrow deemed to be medieval in date. The largest of these, feature 2, is also bisected by a former field boundary depicted on the early 17th-century estate map mentioned earlier, though not shown on either of the 1st edition OS maps. A possible caveat to the lack of medieval finds is feature 9 (see Figure 8); this could be a path or hollow-way, and it appears to cut (and therefore post-dates) the ridge-and-furrow. As the eastern terminus of feature 9 is close to the edge of the park boundary, it may point to the location of the suspected park gate. Its western extent appears to respect the trajectory of the lost field boundary, and there it may represent an early modern, post-medieval feature. For a fuller account of the features revealed by the survey, see the full report.

Although neither survey succeeded in yielding clear evidence to help answer all the research questions we asked at the beginning, they certainly improved our understanding of both areas examined. In the case of the castle earthworks, it is clear that a substantial building once occupied the south-eastern portion of the bailey, and it is now possible to map this accurately in relation to surface-level features. In the case of the park, we can tentatively identify the approximate location of a gate into the park, though we cannot be certain it is medieval in origin. More work may allow us to ascribe dates, or relative phases, to these features.

For English Heritage’s interpretation project at Warkworth Castle, these surveys have been invaluable, and we are grateful for the support of the Castle Studies Trust in pursuing them – especially during the difficulties in completing the surveys resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic. Going forward, the standing buildings of the castle have also been subjected to a separate, detailed analysis, and it is hoped that the bringing together of these two sets of data will offer a fresh understanding the site. Although the research is ongoing, a preliminary integration of both appears offers some new and tantalising ideas about the history of Warkworth Castle. These will inform our presentation of Warkworth Castle to the public, and improve our collective understanding of one of England’s finest castles.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

You can view the full report here: https://www.castlestudiestrust.org/Warkworth-Castle.html