In the second of two articles on the Castle Studies Trust / Historic Environment Scotland co-funded project to date the timber left in a wall socket at Old Wick, Dr Will Wyeth offers an explanation for the surprising date of the timber.

Past investigations of Castle of Old Wick provide a context for the most recent research on this enigmatic Caithness castle. The archaeological evidence combined with historical details give sharp insight into an episode of violence and destruction at the castle in the life of Christian Sutherland, the Lady of Berriedale.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

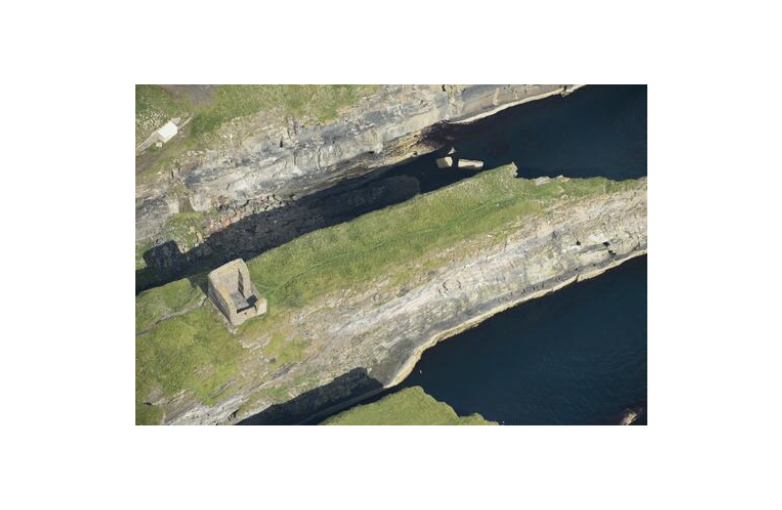

Based on some similarities with Cubbie Roo’s Castle in Orkney, Old Wick’s standing fabric – a unornamented stone tower with small windows – has been dated to the 12th century. A survey in 2016 led by Dr Piers Dixon of Historic Environment Scotland (HES) was the first comprehensive assessment of its standing buildings and earthworks since the publication of MacGibbon and Ross’s Castellated and Domestic Architecture in the late 19th century. Dixon’s study queried the consensus of the castle’s high medieval origins, pointing to regional comparators whose documented history sat more comfortably in a date range beginning in the 14th century. My review of archaeological and historical evidence for Castle of Old Wick in 2019 substantiated the conclusions of the 2016 survey.

Nevertheless, the simple stone towers of Caithness are poorly understood. They are fairly numerous in the county but our understanding of them relies on an unproductive mixture of simplistic architectural study and a reliance on references in historical sources.

Dr Coralie Mills’ and Hamish Darrah’s research gives scope to uphold Dixon’s assertion, and challenge a 12th century date for Castle of Old Wick. Their analysis of the fragment of alder has given the first substantive dating evidence for the castle with a felling date range of 1515-50 (95% probability).

The slot in which the timber was recovered, located on an internal wall face within the tower, was argued by Dixon to be part of a hanging lum. This is a form of fireplace common to buildings of middling and high status in late medieval Britain, also helpful for dating the construction of the tower at Old Wick. A hanging lum is a fireplace whose hearth and flue are built against, not within, a wall.

Mills and Darrah suggest that the alder was a replacement for an earlier timber used for the same purpose, i.e. to support a hanging lum, therefore, the felling date corresponds with a period of repair, restoration or improvement of the interiors of Castle of Old Wick in the early 16th century.

Looting and legitimacy

The historical context is one where violence both within and between kin groups is a feature of elite society in late medieval Britain. Typically, these disputes centred on rights of succession to property and titles. Those held by women were the most precarious. In 1517 two parties from the extended Sutherland of Duffus family met to settle a violent succession dispute at Drumminor Castle in Aberdeenshire. William Sutherland of Duffus agreed to an arbitration on the matter of assisthment (compensation for loss) and kynbut (compensation for manslaughter) with Christian Sutherland (the Lady of Berriedale) and her son and heir, Andrew Oliphant. William and his accomplices were held responsible for the murder of Christian’s elder son Charles. Duffus was also accused of seizing and looting two of her properties: Berriedale Castle and Castle of Old Wick.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

The family dispute which led to the murder of Charles Sutherland originated in the legitimacy of Christian’s inheritance of several estates on the death of her father, Alexander Sutherland (d. 1451×1471), including those in Caithness but also Duffus and elsewhere. William Sutherland’s father, also William Sutherland of the fittingly named Quarrelwood, contended that Christian was illegitimate. The court of the Bishop of Aberdeen had found in favour of Christian in 1494, but two years later Quarrelwood violently seized Castle of Old Wick. This was very likely not the same occupation mentioned in the 1517 document. Still unsatisfied, Quarrelwood pursued his case in the court in Rome for several years, until a settlement of sorts around 1507, when Christian surrendered her father’s Duffus lands.

We don’t know exactly why she reached this settlement but it may be telling that her husband’s kin, the Oliphants, had spent substantial sums (not entirely selflessly) on supporting her legal case and accommodating Christian and her children during the difficult years of legal wrangling. We also can’t be sure if the 1517 document references this settlement, or another outburst of violence.

It is tempting to connect the episode of refurbishment at Castle of Old Wick implied by the radiocarbon dating and the documented evidence of looting at the castle which took place before the 1517 settlement, with the implication of subsequent repairs implied by that settlement. I think this is the best conclusion, but others are possible. Between 1515-50 the castle was held by at least seven different parties, but evidence suggests that they were either in financial difficulty or held the castle to generate money from its lands, not as a family seat. Only when the senior branch of the Oliphants take over after 1548 is there a compelling reason to think that the castle was systematically renovated: this is the best alternative scenario to that suggested above.

Archaeologists’ efforts over the last six years have drastically altered our understanding of the Castle of Old Wick. But they have also shed light on the story of Christian Sutherland and violence and upheaval occasioned by her kinsman’s legal contestation. This research demonstrates the value of revisiting the smaller castles of the world, for the potential to challenge an existing consensus as well as shed light on lesser-told stories from the medieval past.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

To read the first blog by Dr Coralie Mills and Hamish Darrah click here:

One thought on “Castle of Old Wick: Hot Fire and Cold Murder: Looting and Legitimacy in late medieval Caithness”