Neil Ludlow, co-project lead in both the Castle Studies Trust funded 2016 geophysical survey and 2018 excavations looks at Pembroke Castle’s most iconic structure, it’s keep.

Pembroke Castle is probably best-known for its magnificent cylindrical keep, begun in 1201-2. But why was it built? And how was it used? These and other questions are being explored as part of the wider study of the castle.

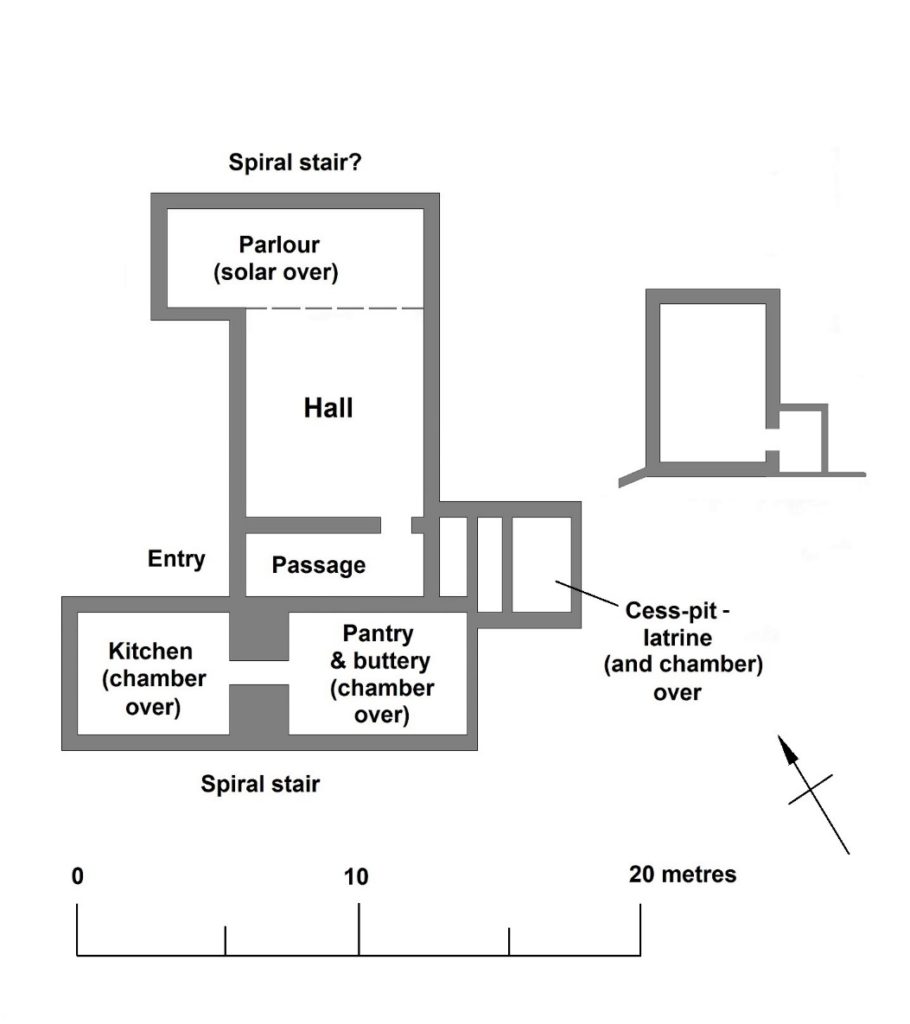

Great keeps like these were bold statements of power and prestige. At Pembroke, it seems the keep was also celebratory and commemorative, marking the marriage, ennoblement and inheritance of its builder, William Marshal – and in the most conspicuous way. But it was not intended for residential use: there is neither bedchamber, latrine nor water supply. Household accommodation was instead provided by the great hall, while a chamber block served the Marshal earls on their rare visits to Pembroke.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Use of the keep, as intended, was restricted and episodic, probably confined to the handful of occasions when the earl visited. Access was clearly limited to those above a certain rank – for instance, there is only one spiral stair and no separate stair for lower ranks. And the interior had to be crossed to get to the stair, showing that its use was strictly controlled.

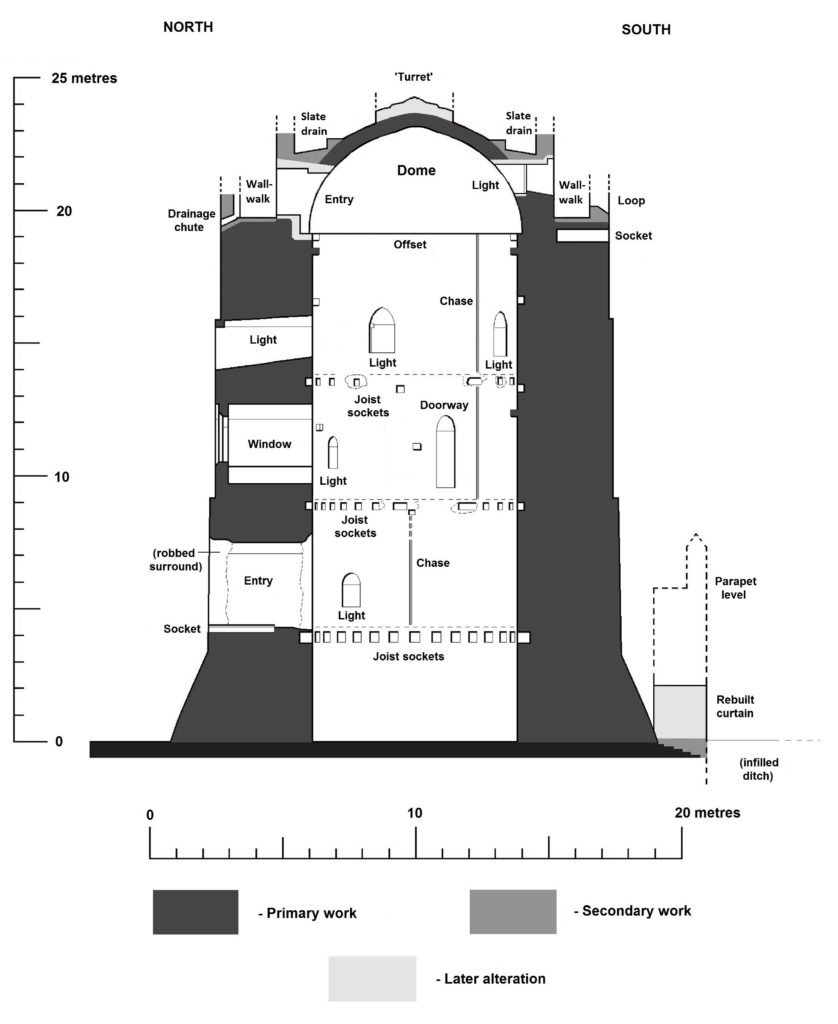

The main chamber lay on the second floor, which has a high-quality window and a fireplace. It may have been intended as an audience or reception chamber, and a setting for formal and ceremonial occasions. It has been suggested that its external doorway was served by an external bridge and stair from the curtain wall, but such an arrangement is inconsistent with the remains. The doorway may instead have led onto an appearance balcony, visible from the town before the outer bailey was added and allowing the earls to be seen by their subjects. Similar balconies existed at King Henry II’s round keeps in France.

The first floor, at entrance level, may have been an anteroom or ‘waiting area’ for the second floor. It too has a fireplace. The uppermost chamber lies beneath the unique, masonry dome. It lacks a fireplace, suggesting events here were of short duration. Nevertheless, it is lit by a second elaborate window, while a decorative painted scene can perhaps be envisaged on the underside of the dome. It may have been a ‘prospect chamber’ for entertaining special guests. Other openings, at all levels, are very narrow slits which are too small, too narrow and too high up to have been used by archers, and were probably for light and ventilation only.

At summit level, at least one major change in design occurred during construction, which culminated with the crenellated parapet and concentric inner wall that now crown the keep. As originally built, the dome seems to have been circled by a wide, slate-lined drainage channel. The slates are fossilised, as a series of crests and troughs, within the concentric inner wall and seem to have been truncated when the present wall-walk was established. It is not known whether they were contemporary with the overhanging timber hourd, the sockets for which can be seen beneath the present parapet, but it is difficult to envisage how the two could have worked together.

Hourds like this are now thought to have often been leisure-related rather than military,providing a viewpoint from which a lord’s estates could be shown off to his important guests. At any rate, this overall scheme was replaced, possibly before it was complete, by the present parapet, wall-walk and concentric inner wall. Another slate channel, within the latter, runs around the haunches of the dome and is of very similar design to the earlier drain. These substantial drainage arrangements may indicate that the dome was not roofed, perhaps instead being finished with slates like the domes of some later medieval church towers in south Pembrokeshire.

Much later alterations at summit level included the insertion of a floor beneath the dome – creating an attic space which was accessed from the wall-walk through a secondary doorway, and lit by crudely-inserted window – showing how the keep’s role changed through time, with loss of its original prestige. And much of the dome’s facework was robbed, perhaps to make the central ‘turret’ that now occupies the summit. Part of the second drainage channel was removed in order to create access to this turret, confirming that it is a later addition, but it was present by c.1600 when it was shown in a sketch of the castle.

Either one of these summit alterations may be contemporary with the partition in the body of the keep, the chase (or scar) for which survives in the internal plaster. The plaster contains coal fragments; a corresponding absence of charcoal suggests that the present finish may itself be late, but also means that it cannot be radiocarbon-dated.

Pembroke Castle keep from north (feature photo) Adam Stanford @ Aerial-Cam