The conquest of Wales in 1283 did more than enforce English military control over Gwynedd: it reshaped the cultural and symbolic landscape of both the principality and its borderlands. At the centre of this transformation was Queen Eleanor of Castile. Though often overshadowed by her husband, King Edward I, Eleanor’s influence on the ideological dimensions of conquest has received increasing attention. My recent publication has focused on Caernarfon Castle in Gwynedd, re-evaluating its design in the light of Eleanor’s cultural and political presence: see Living the Dream. This blog also touches briefly on her involvement with Overton, historically in Flintshire and now part of Wrexham Borough.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Eleanor’s broader impact on the architectural and material culture of the crown is becoming more widely acknowledged, especially in relation to estates and gardens. Yet her role in the narrative landscapes of conquest, particularly in Wales, has remained underexplored. Caernarfon Castle, long seen primarily as a fortress and statement of English dominance, may also be read as part of a more deliberate, symbolic project – one in which Eleanor’s influence shaped both meaning and memory.

Born into the Castilian royal family around 1241, Eleanor brought with her an appreciation for garden culture, symbolic space, and the communicative potential of architecture. She shared Edward’s interest in Arthurian and Roman imperial narratives, themes that appear in the design language of his castle builds in Gwynedd. At Caernarfon, such symbolism could well have echoed ideas of conquest – not simply as occupation, but as renewal through continuity and legend.

Caernarfon Castle’s banded masonry may have been intended to recall the Theodosian walls of Constantinople, visually linking Edward’s authority with that of Roman emperors. Its location near the Roman fort of Segontium strengthens this earlier interpretation, suggesting a conscious linking of past imperial power to present rule. Yet the site also draws from native Welsh tradition, particularly from the medieval Welsh romance, The Dream of Macsen Wledig, in which the Roman emperor Macsen dreams of a great fortress beside a river, where he meets Elen Luyddog, a Welsh noblewoman who becomes his queen.

Macsen Wledig is not merely mythical: he corresponds to the historical figure Magnus Maximus, proclaimed emperor in Britannia, and later Gaul, in the late 4th century and whose memory was preserved in Welsh legend and genealogy. Magnus was said to have married his daughter to the British king Vortigern—a story enshrined on the Pillar of Eliseg near Valle Crucis Abbey in Denbighshire. The alignment of Eleanor with Elen—a queen associated with building, mediation, and dynastic continuity—would have positioned her within a narrative of legitimacy that transcended simple conquest.

This symbolic layering is most clearly visible at the Queen’s Gate at Caernarfon. Set above the landscape beyond and to the east of the walls of the castle and town walls, and with no obvious external access, I suggest that the gate served as a gloriette: an elevated, private space from which the castle’s elite landscape could be viewed. It overlooked a garden laid out in the former bailey of the Earl of Chester’s late-11th-century motte-and-bailey castle, recorded in 1284 as the garden previously belonging to the Welsh Prince’s llys (palace). This elevated viewpoint and garden arrangement is strikingly like Eleanor’s garden and gloriette at Leeds Castle, constructed in 1278. Replacing the former garden of the Welsh Princes, therefore, Eleanor transformed a site of pre-conquest identity into an English and Castilian landscape at Caernarfon.

Beyond the garden lay the route later known as the King’s Way, following an old Roman road from the Queen’s Gate from the east of the castle site to Segontium fort and the early Christian site of St Peblig. This axis—linking Roman, sacred, and regal geographies—was further extended through the nearby royal hunting park at Coed Helen. The resulting landscape echoed and enhanced upon the ceremonial design of Eleanor’s other gardens and estates, and brought together memory, power, and place.

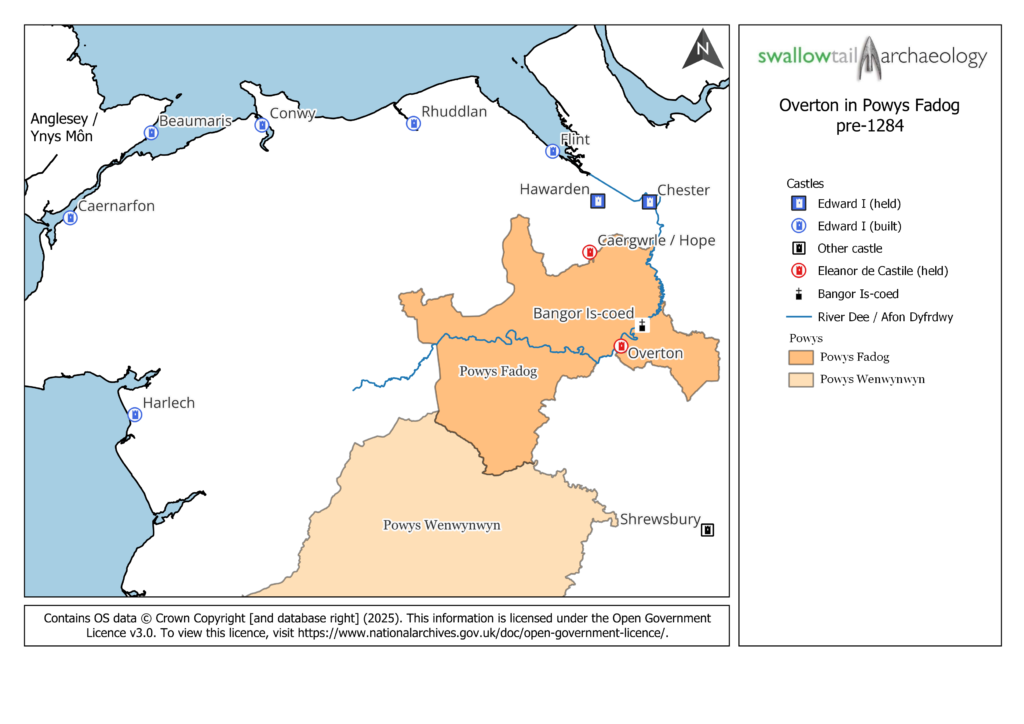

Elsewhere, Eleanor’s influence now appears more discreetly. At Overton, then in Flintshire, granted to her as part of her dower lands in 1283, the traces of Eleanor’s presence are quieter but still significant. The site—once a Powysian princely centre—was visited multiple times by Eleanor and Edward and was elevated to borough status in 1292. Contemporary sources refer to a castle, chapel, mill, and gardens. In 1284, Eleanor commissioned stained glass for the chapel and hosted a feast there with the entertainment of over 1,000 Welsh minstrels – an ostentatious display of political theatre.

Overton’s significance extended beyond its material fabric. It lay within a region imbued with historical and legendary associations, particularly those of Powys, whose rulers claimed descent from Magnus Maximus. This legendary lineage, recorded on the Pillar of Eliseg near Valle Crucis Abbey, presented Powys as a kingdom with both Roman and British roots.

The geography of Powys is also preserved in another legendary dream: The Dream of Rhonabwy, a Middle Welsh tale set during the reign of Madog ap Maredudd, the last prince of the entire kingdom of Powys. In this story, Rhonabwy dreams of travelling back to the court of King Arthur, and the landscape described places Powys stretching from Porffordd (modern Pulford in Cheshire, north of Overton) to Gwarfan in Arwystli.

By considering Caernarfon and Overton together—not as isolated places, but as connected elements within Eleanor’s political and symbolic geography—we gain a deeper understanding of how legend, landscape, and queenship intersected in the making of English authority in Wales. Eleanor emerges not simply as a consort, but as a queen whose influence shaped a vision of rule grounded in ancient Welsh tales, place, and space.

My ongoing research and future publication are uncovering the form and probable siting of the lost castle at Overton, revealing its full role within the broader narrative of royal presence and designed landscape. Watch this space!

Rachel Swallow FSA (Swallowtail Archaeology ) is an archaeologist whose research has reshaped our understanding of castles and their landscapes. Elected as a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London in 2018, her work explores the social, political, and architectural significance of these sites within their broader contexts. Rachel completed her PhD in 2015, and she is a Visiting Research Fellow at the University of Chester and holds an honorary fellowship at the University of Liverpool.