Over the last two decades, the Marlborough Mound Trust has carried out extensive conservation and investigations on the ‘mound’ in the grounds of Marlborough College. The origins of the mound were uncertain until recently. It was known to have been part of Marlborough Castle, but there had been persistent speculation, on the strength of its resemblance to neighbouring Silbury Hill and the discovery of antlers in the early twentieth century (now lost) that it was of prehistoric origin. In 2008, when Silbury Hill was being investigated, the opportunity of taking cores from the mound to obtain comparative dates presented itself. After a precarious operation involving a very large crane, the necessary drilling rig was hoisted to the top of the mound. The resulting cores, as a paper published the following year by Jim Leary and his colleagues showed, supported a date in the second half of the third millennium BC, broadly contemporary with Silbury Hill.

Jim Leary has subsequently carried out a survey of some fifty castle mottes, looking for other sites where prehistoric mounds could have been reused as the base for a castle, and has found only one other rather uncertain case. This means that Marlborough may be unique in being a prehistoric structure recycled into a medieval castle.

But we now know more about the prehistory of the mound than the supposed castle keep. The only possible sighting of masonry on the mound is uncertain in the extreme. H. C. Brentnall, a master at Marlborough College, in one of his many contributions to the Proceedings of the College’s Natural History Society on the the history of the castle, had this to say in 1936:

“Excavations necessitated by building operations at Marlborough College in the course of this summer have revealed several traces of the medieval castle which perished gradually between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries. What little remains above ground (if the elevation justifies that expression) is to be seen on the summit of the motte, where a buttress of the keep was laid bare some years ago.“

The note implies that the buttress was visible in 1936, but recent geophysical surveys have not found it.

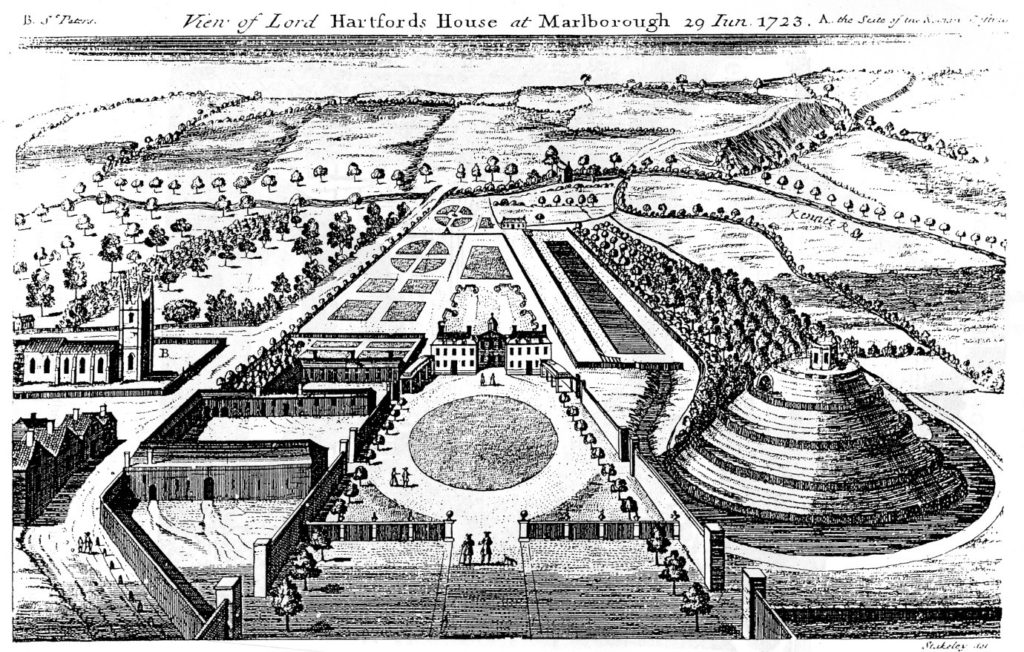

The problem is further compounded by the subsequent use of the mound. It became a garden feature in the seventeenth century, and a spiral was cut into the side of it to give access to a summerhouse at the top. Stukeley’s engraving of the countess of Hertford’s gardens in 1723 shows only the summerhouse, and no traces of masonry.

About the same time, a water tank was installed to supply the Hertfords’ newly built mansion. This was enlarged by the College after its establishment in 1843, and adapted over the years, until the top of the mound was graced by a large iron tank surrounded by a spoil bank, concrete steps, and substantial pipework. This meant that in effect most of the original top of the mound had been destroyed.

This raises the question of what we are looking for. The earliest mentions of the site, in 1070 and 1110, present the king’s establishment as a place of imprisonment and a site where a royal court was held. In the 1140s, Marlborough castle is first mentioned as such. It is described ‘very defensible’ in The Deeds of King Stephen. It was held by John Marshal, who used it to control the surrounding countryside, and there is no record of it ever being attacked.

The only entry in the plentiful records for the castle under Henry II and Henry III is in the context of payments in 1222 for work designed to create a substantial royal residence there. This is a single sum for the building of a lime kiln ‘for the Great Tower’, which must therefore have been of stone. There is no indication where this tower was sited, and it may well have been part of the lower bailey. It has simply been assumed that it was on the mound.

An inconclusive exploratory dig was carried out by Wessex Archaeology for the Mound Trust in 2019, and at the time of writing, it is still hoped that a follow up to this will be possible in 2020. The present assumption is that the mound was among the hastily erected timber forts from immediately after the Norman conquest, and that this was replaced by a stone keep after 1222. It would be good to be able to find some actual evidence as to the nature and even the existence of the keep at Marlborough.

Richard Barber is a trustee of the Marlborough Mound. He would welcome any comments, particularly on the replacement of timber with stone, and the nature of ‘great towers’: email rwbarberuk at yahoo.co.uk.