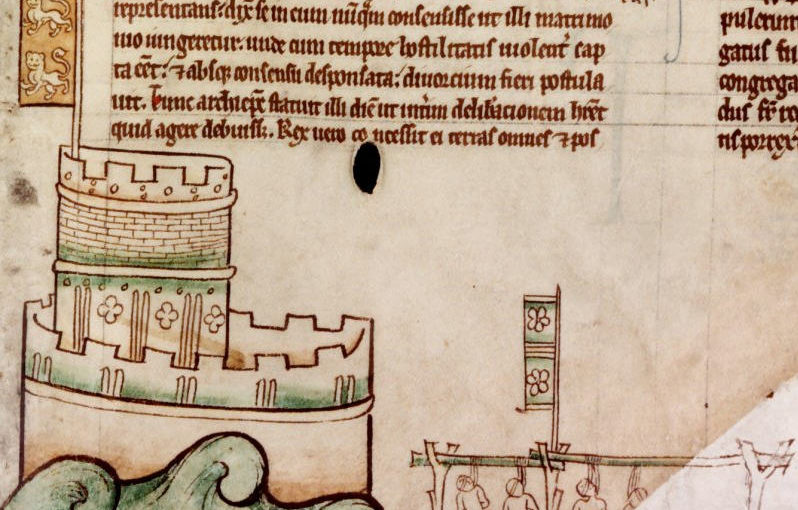

Slighting is the destruction of a high-status building, and in the Middle Ages it was all about power: damaging property meant exercising power over its owner. Castles were statements of the owners’ strength and status, so damaging one said a lot about how that status had changed, or their strength undermined. One especially interesting example comes from Bedford Castle.

During King John’s war with the barons in 1215–16 one of his captains was Falkes de Breauté. Falkes seized control of Bedford Castle from William de Beauchamp who had joined the rebellion against John. John died in 1216 and was succeeded by his son, Henry III; Falkes was a key figure at the battle of Lincoln in 1217 which ended the rebellion against royal power and secured Henry’s reign.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

After the war ended, Falkes made himself at home in Bedford, expanding the castle and even tearing down two churches in the process. At the same time, William de Beauchamp was trying to persuade the young Henry III to give him back Bedford Castle. Falkes was a powerful man in the royal court, despite making enemies. He clashed with Hubert de Burgh, who was Henry III’s justiciar, and in November 1223 Falkes nearly sparked a new civil war by attempting to seize the Tower of London alongside the earls of Chester and Gloucester and the count of Aumale.

Falkes lost a lot of power and influence because of this failed gambit and in 1224, he was instructed to give up Bedford Castle (along with some other properties). Falkes refused and things came to a head in June when Falkes’ brother, William de Bréauté, imprisoned a royal official at Bedford Castle.

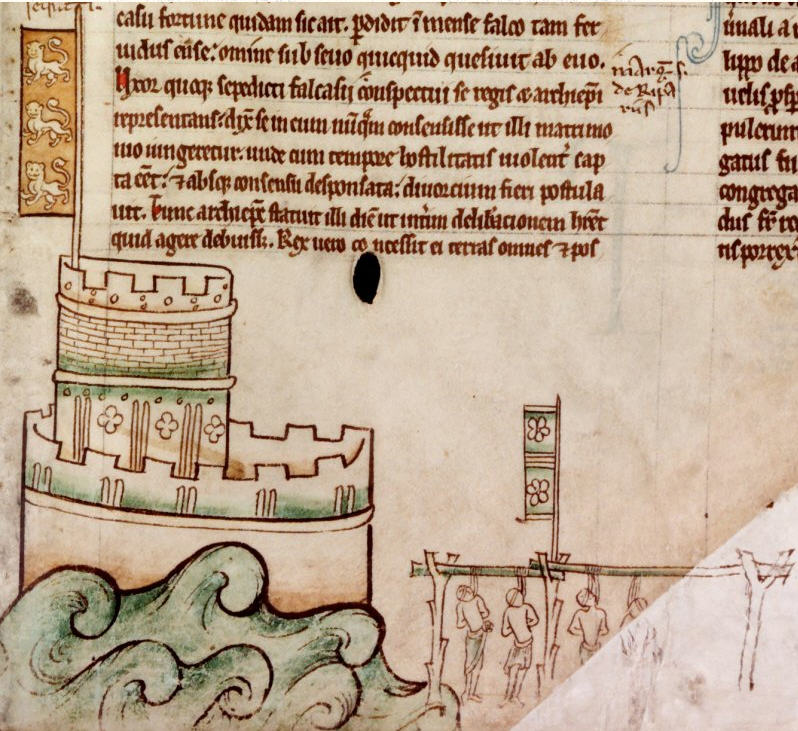

William had been left in charge of Bedford Castle, and Falkes supported his brother’s refusal to release the royal official and surrender the castle to the king. Henry quickly diverted the army he was gathering for an expedition to Poitou to undertake a full blown siege of Bedford Castle. Falkes might have hoped he would get some support from his allies, including the earl of Chester but he was left isolated. An eight-week siege followed, with four attacks on the castle and more than 200 deaths on the side of the royalists. William led the defence of the castle while Falkes fled to safety. Bedford Castle’s garrison surrendered on 14 August and all of them, including William, were swiftly executed.

With Falkes asking Henry III for forgiveness, the king had all the power to decide what to do next. He could give Bedford Castle to William de Beauchamp, the previous owner who had been seeking its return for years. He could keep it under direct royal control, or he could slight it – unmaking the castle expanded by Falkes. Henry III chose the destructive option: royal records show that the tower was levelled, the ditches filled, buildings in the outer bailey demolished, and the walls of the lesser bailey lowered. This amount of detail in the historical record is unusual, and where we do have details of castle slighting they are often much more brief and may just cover how much was spent.

Excavations between 1969 and 1972 found evidence of the castle’s destruction, with plenty of rubble strewn across the site. They also showed that the motte was lowered, which wasn’t mentioned in the royal records. The slighting of the castle was an especially destructive event. There are many other castles which were slighted where the destruction was less extensive, or the castle later repaired and rebuilt. At Bedford, that was never an option.

With no allies left, a wife seeking divorce, and having turned over all his lands to royal control, Falkes went into exile. Henry III did eventually grant the castle to William de Beauchamp on the condition that only an unfortified house could be built on the castle.

The destruction of Bedford Castle was a high-profile way for Henry III to reassert his authority after having been challenged by Falkes de Breauté. In the Middle Ages, not every slighted castle was the result of a royal order, but they were the majority. Visiting Bedford Castle today, there isn’t much to see, but in the early 13th century it was a strong stone-built fortress. Its destruction emphatically marked Falkes’ fall from power.

For many slighted castles we often only have archaeological or documentary evidence; at Bedford we are lucky enough that they coincide so we can confirm the documented events took place and give context to the evidence of destruction on the ground.

For more on slighting generally, you can read Richard’s paper in The Archaeological Journal.