On Saturday, 24 August, the Higgins Museum in Bedford hosts an event to mark eight centuries since the town’s castle was subject to an 8-week long siege by the army of the teenage King Henry III (booking details at the end). Dr Peter Purton, FSA, outlines what happened in the siege.

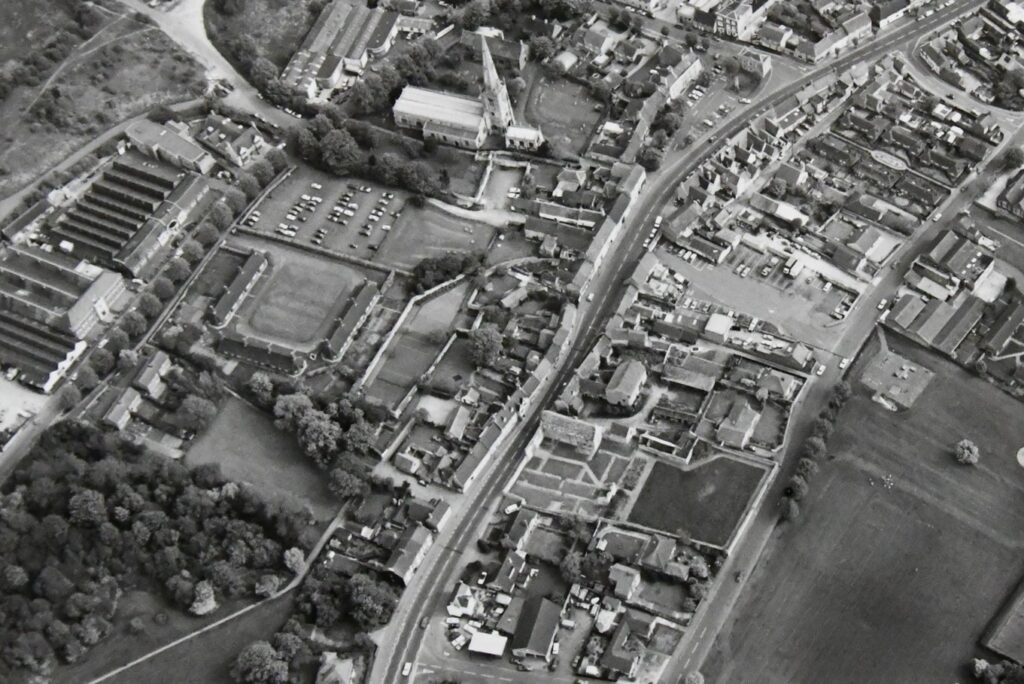

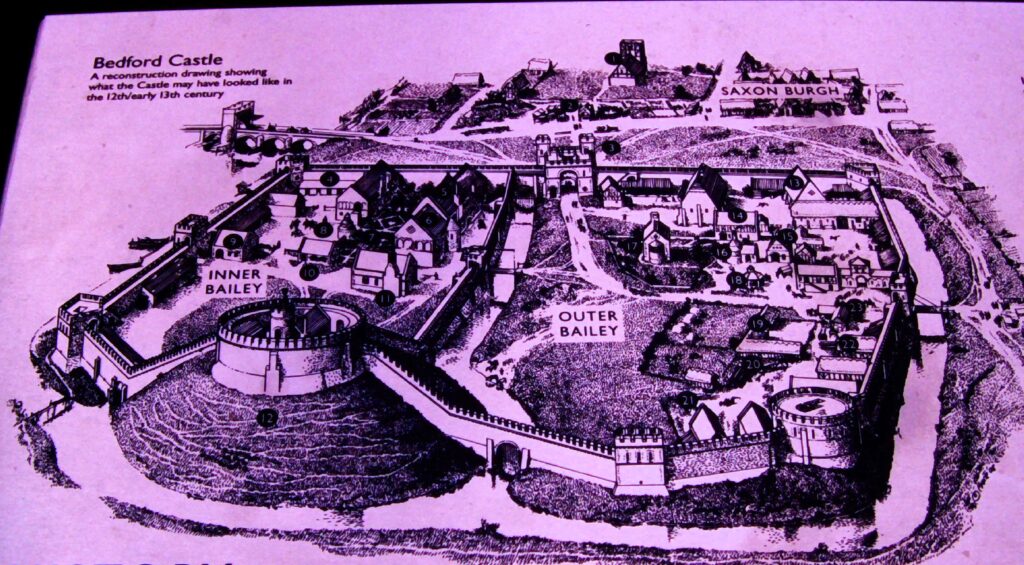

Not much remains now of Bedford Castle – just a degraded and much altered mound near the river Great Ouse in the town centre and a few excavated fragments of stone buildings, making it hard to visualise that it was once a large stone-built fortress with a moat, barbican, two wards and a stone tower on top of the motte which marked the original castle built after the Norman Conquest. A display board nearby reconstructs its possible appearance in 1224.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

In that year, Henry III was assembling an army which was to be transported to France in an attempt to recover Poitou, part of the once extensive Angevin empire. This plan unravelled with the rebellion of Fawkes de Breauté. Fawkes had been one of the captains of King John, Henry’s father, and had become rich and powerful. He had been granted Bedford castle and we are told that he had strengthened the fortifications to make it “impregnable”. Rebelling against the crown, he prudently left the country while leaving Bedford in the hands of his brother, who in arresting the justices sent there by the king made it inevitable that he would face royal retribution: this was a direct insult to royal authority and following years of civil war and rebellion following John’s reign, there was no possibility that it could be ignored. The royal army, assembling conveniently nearby at Northampton, was diverted to Bedford. What happened next was recorded in several contemporary chronicles while royal expenditure was detailed in surviving accounts, a combination of evidence which is rare enough and which allows an unusually detailed reconstruction of the siege.

The royal army deployed seven stone-throwing engines (mangonels and petraries) and built two siege towers but the garrison resisted stoutly and inflicted heavy casualties on the attackers. Eventually the barbican and outer ward were breached and captured by royal soldiers then miners, summoned from the Forest of Dean, brought down the wall of the inner bailey and did the same with the tower on the motte, to which the defenders had withdrawn. The prisoners were set free and the entire garrison was hanged as punishment for their rebellion. The castle was then demolished. A period of instability in England was thereby ended, but so too was English rule in Poitou, the French capturing La Rochelle at the same time as Bedford was being besieged.

These events were therefore of international as well as national significance, and through archaeology, it is possible to now know much more about Bedford castle. All these themes will be discussed at the conference on 24 August, the speakers are Professor David Carpenter, expert and author specialising in this period, Dr James Petre who has written about Bedford, Ben Murtagh who has been exploring Bedford Castle, Jeremy Oetgen (Albion Archaeology) who will update us on a long history of archaeology on the site, and the author of this blog who will place the siege in the context of contemporary siege warfare.

Anyone interested in attending can find all the details and book a ticket at the museum website: www.thehigginsbedford.org.uk. Tickets cost £15 and advance booking is encouraged.