In the latest in is “Defending…” series looking at the fortifications in particular counties, Mike Osborne looks at Bedfordshire.

When I wrote Defending Lincolnshire: a military history from the Conquest to the Cold War (The History Press, 2010), I had no idea that ten years on, the series would have grown to cover ten counties with an eleventh almost completed. What I have discovered along the way is that while there exist clear cultural similarities, counties are patently different in so many regards. Some of these differences are obvious: the landscape factors which affect settlement patterns; the geology which dictates building materials and factors such as moated sites; the county’s relationship to important routes and its density of urban or rural settlements; its central or remote position within the nation; its relative vulnerability to invasion; and, above all, its recorded history. Other differences are more subtle and may be governed by local conditions and circumstances: the dominance of particular families or factions; the power struggles of kings, nobles or bishops; the economic effects of trade or farming; fashion and technology; continuity and re-use of defensive locations and the impact of localised, country-wide or international conflict. Taking the wider context of these studies which embrace all forms of fortification and military activity from Iron Age forts to nuclear bunkers, then such differences will only be magnified.

The motte at Cainhoe (copyright Mike Osborne

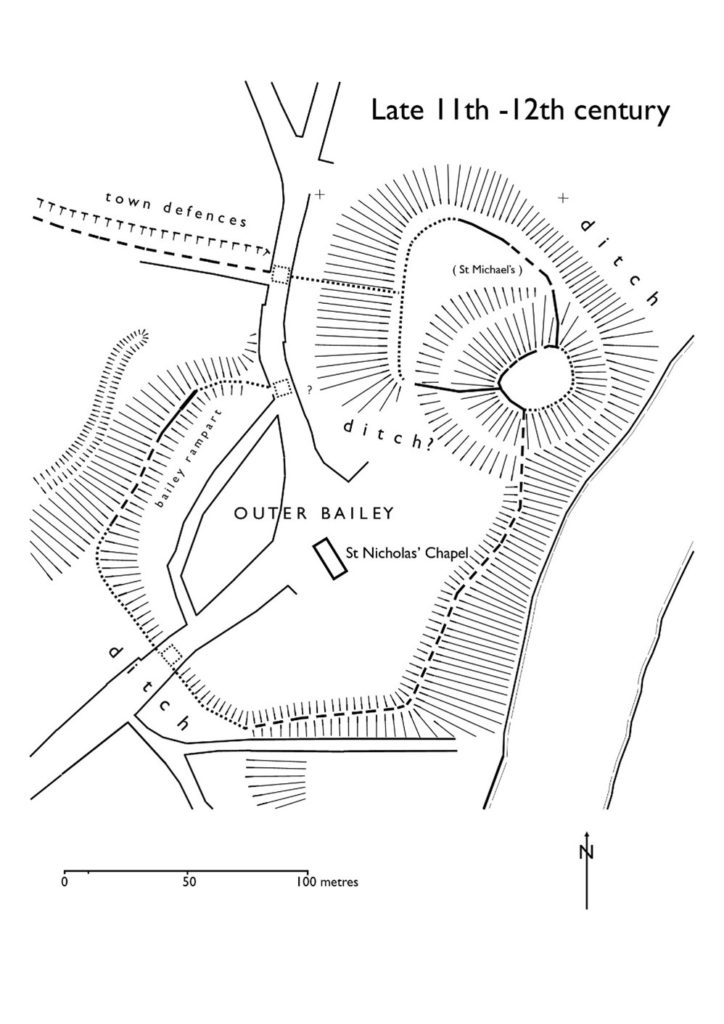

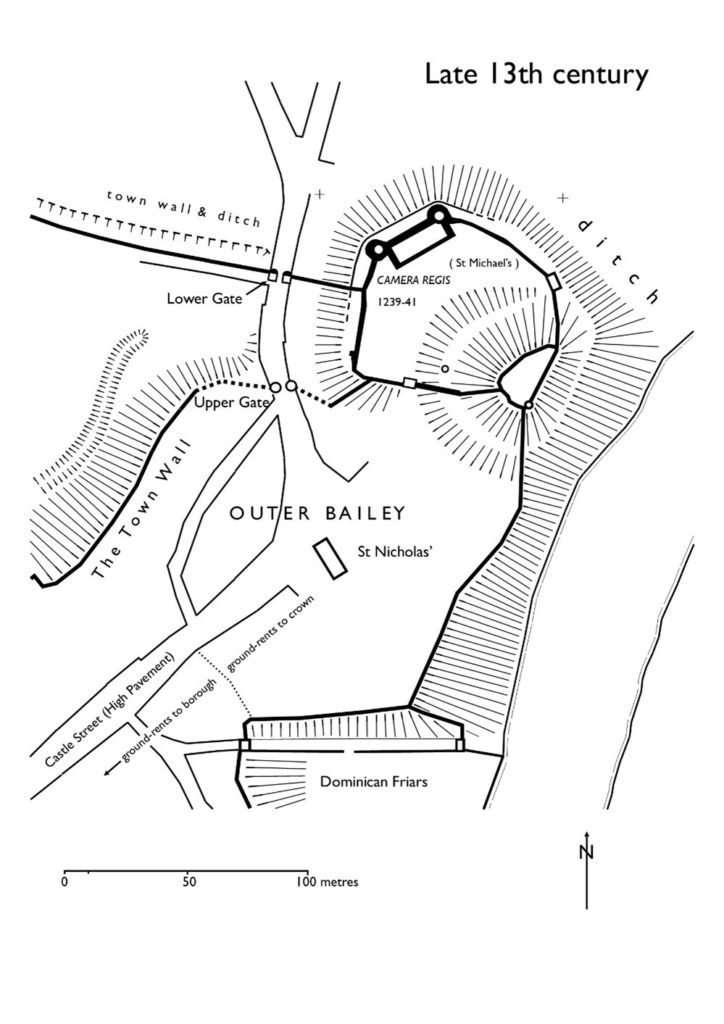

Bedfordshire is unusual in that whilst there were Romano-British settlements and an established network of Roman roads: Watling Street, Ermine Street and the Icknield Way, there were, apparently, no Roman forts. Bedford became established only in Saxon/Danish times, owing to its strategic position astride the Great Ouse, and Clapham’s church-tower, on the border of Wessex and the Danelaw may well have served a defensive function. Sadly, despite the public promotion of Danes Camp at Willington and Tempsford as Viking river-side fortresses, they have both been found to be medieval moated sites. Luton only developed after the Norman Conquest becoming the location for two earthwork castles. A ‘royal’ castle was established at Bedford, soon to evolve into a masonry fortress, but the county’s numerous motte castles, notably Cainhoe, Yielden, Risinghoe and Totternhoe, and its fewer ringworks, whilst remaining as structures of earth and timber throughout, nevertheless often occupied dominant sites. Historical factors around conflict saw Bedford erased as a fortification early in its career having undergone two sieges, and most of the other castles would be superseded by more comfortable accommodation. The county was split into an unusually large number of small manors which may account for the over twenty earthwork castles and the 300+ homestead moats- the greatest density of any English county- benefiting from the underlying clay. Bedfordshire’s later medieval castles, Wrest Park, Bletsoe and Ampthill, have disappeared, but remnants of Someries survive to the background sound, in normal times, of Easyjet. Whilst largely insulated against external threats, the county still experienced the effects of conflict during the civil war between Stephen and the Empress and the Wars of the Roses, whilst suffering its share of the universal effects of famine, plague and social disorder. Probably the best-known castle-related event was the siege of Bedford by Henry III in 1224 which resulted in the destruction of the castle but not, in all likelihood, the draconian penalties reputedly enacted against the garrison.

Were anyone to ask me which of these counties had been the most interesting, given their differences, I should be pushed to answer. From the perspective of fortification, some will share similarities: Essex, Norfolk, and Hampshire as targets for invasion; the Midland counties of Nottinghamshire, Northamptonshire and Leicestershire/Rutland controlling lines of communication from urban centres; Bedfordshire, Lincolnshire and Cambridgeshire sharing elements of landscape; whilst London has a bit of everything as, I am currently discovering, has Gloucestershire and Bristol. All of them have interesting facets either shared or individual, common or unique. Rob Liddiard, amongst others, has confirmed to me the value of the local focus alongside other approaches, and it is certainly something I will continue to explore.

Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter

Defending Bedfordshire: the military landscape from pre-history to the present (Fonthill Media, 2021) is now available along with other counties.

Captions

Featured image: A model of how Bedford Castle may have appeared around the time of the siege of 1224